As a language learning addict, I follow lots (and I mean lots) of polyglot blogs and podcasts. It is always interesting to see what has worked (and what hasn’t worked) for successful language learners. While most fluent foreign language speakers tend to agree on the vast majority of language learning DOs and DON’Ts, there is one area that always seems to cause heated debate, shouting, name calling, and occasional mud/poo flinging: the importance of language input (i.e. listening and reading) versus language output (i.e. speaking and writing).

I have sat quietly on the sidelines for some time now, politely listening to both sides of the argument. But it’s time to blow my referee whistle because both teams are “offsides” (Okay John, enough sports analogies already!)

The Argument is Flawed to Begin With…

The problem with the whole argument is that input and output are not mutually exclusive components of language learning. You need both. The key is order and balance.

1. Listen first, then speak

When just starting out in a language, it is important to get as much listening input as possible. Just like when you learned your first language, you need to first go through a “silent period” where your brain gets used to the patterns and phonology of the language. Once you have filled your teapot up with enough listening input, language will naturally want to start pouring out. That’s when it’s time for a tea party to put into practice what you have assimilated (and no, I am not promoting that kind of “tea party” as I am a bleeding-heart liberal…)

When just starting out in a language, it is important to get as much listening input as possible. Just like when you learned your first language, you need to first go through a “silent period” where your brain gets used to the patterns and phonology of the language. Once you have filled your teapot up with enough listening input, language will naturally want to start pouring out. That’s when it’s time for a tea party to put into practice what you have assimilated (and no, I am not promoting that kind of “tea party” as I am a bleeding-heart liberal…)

But unlike little babies, adults can also rely on reading input to back up what we listen to. This difference (along with the fact we don’t have to wear diapers) gives adults a major leg up on babies learning their first language.

To this end, try to find short, simple dialogues of actual native speakers with transcripts. Then listen and read, listen and read, and listen and read again as many times as your schedule and sanity allow. My personal favorite transcript-equipped podcasts are produced by Praxis Language (ChinesePod

, SpanishPod

, FrenchPod

, ItalianPod

and EnglishPod

) and LingQ (English, French, Russian, Spanish, German, Portuguese, Italian, Korean, Chinese, Japanese, and Swedish). I can’t stand the overly stilted, monotonous dialogues found on most textbook companion CDs and suggest you avoid them like the plague.

2. Take equal doses of your input and output medicine.

Once you have gone through your silent period (which will be input-centric by definition), try to spend an equal amount of time on input activities (listening to podcasts, reading blogs, etc.) and output activities (speaking with friends or tutors, writing a blog post in the foreign language, etc.). It may be nerdy, but I literally use the stop-watch feature on my iPod touch to time my input and output activities each day…

If you follow the above regimen, your foreign language skills will progress quickly, efficiently, and most importantly, enjoyably. However, if you follow the advice of the extremists on either side of the input-output debate, you are in for heaps of problems and a world of pain. Here’s why:

Output Only Problems

Proponents of the “Output is awesome; input is lame” philosophy suggest that learners just “get out there and start communicating with native speakers”. This approach, while certainly sexier than what I prescribe above, has a number of problems:

1. Nasty mispronunciation habits.

Bad pronunciation habits develop when you pronounce things how you think they should be pronounced based on your overly limited listening exposure to the language, and your logical, but nonetheless incorrect, assumptions based on how words are spelled but not pronounced.

2. You’ll be that annoying guy at the bar.

Because you have a limited vocabulary and only understand little of what is said to you, you will likely attempt to control conversations by keeping them on topics you are familiar with, using phrases and vocabulary you have memorized. All but the most patient interlocutors will get bored or annoyed by such one-sided conversations. Don’t be that guy.

3. You probably won’t enjoy the process and give up early.

Many would-be language learners give up because they simply don’t enjoy the process. Much of the angst, tedium and phobias stem from having to speak before one is ready. Language teachers are the worst perpetrators, presenting you with new words or phrases one minute, and then expecting you to actually use them the next. Well-meaning friends or language partners are no better, trying to “teach” you new words and phrases and expecting that you can actually use them right away. Assimilation takes time and repetition, so don’t beat yourself up if it takes a few times (or a few hundred times) of hearing or reading a new word or phrase before you can actually use it.

Input Only Problems

If, however, you spend months and months diligently listening to your iPod and reading online newspapers, but never actually speaking with native speakers (by design or chance), you will understand quite a bit of what goes on around you but will struggle to actually verbalize your thoughts well or have natural exchanges with native speakers. This happens because:

1. Proper pronunciation is a physical feat.

You can’t think your way through pronunciation (believe me, most introverts have tried and failed!). Good pronunciation requires that your ears first get used to the new language (i.e. through getting lots and lots of listening input), and then also getting your lips, tongue and larynx used to new sounds not found in your native tongue, which of course takes lots and lots of talkin’ the talk.

2. Speaking and writing identifies your learning gaps.

Until you actually try to say or write something, you won’t know what you really know. While you may passively recognize certain words, phrases, idioms or Chinese characters, you may still struggle to say or write them. This is even true for your native language (as I found out when I first started teaching English and was confronted with such conundrums up at the white board as “Wait a second…How in the hell do you spell “misspelled”?)

The more you speak and write, the more you know where the “holes” are in your language cheese, and the easier it will be to fill them with focused study and review.

Conclusion

So as in all things, the extremists tend to be just that: extreme. They tend to get more attention, but the efficacy of their advice tends to be an inverse proportion to their popularity…

To become fluent in a language, just consume a balanced diet, rich in listening and speaking, with plenty of reading and writing sprinkled in for flavor.

]]>Antonio Graceffo is an applied linguist, and martial arts and adventure author living in Asia (check out our interview with him here). His books, including ”The Monk from Brooklyn”, are available at Amazon.com .

.

Normally, ALG says you do 800 hours of listening, then you start speaking, and you do writing and reading last. The reality is, however, if you are not at the ALG school in Bangkok, it is nearly impossible to arrange these type of lessons for yourself. And, strict ALG takes two years to learn a category three language, such as Chinese, Thai or Korean. Most people working in a foreign country can’t invest two years in learning, particularly if they are on a one year or two year contract.

Normally, ALG says you do 800 hours of listening, then you start speaking, and you do writing and reading last. The reality is, however, if you are not at the ALG school in Bangkok, it is nearly impossible to arrange these type of lessons for yourself. And, strict ALG takes two years to learn a category three language, such as Chinese, Thai or Korean. Most people working in a foreign country can’t invest two years in learning, particularly if they are on a one year or two year contract.

So, I modify ALG when I am doing my own learning and writing.

Next, the founders of ALG were concentrated on how to teach Thai to foreigners. In taking ALG out of Thailand and applying it to other countries, my personal feeling is that the game changes a bit because, unlike Thai, Korean is not tonal and the pronunciation is simple consonant vowel, consonant vowel. And second, the Thai writing system is extremely complex and you really shouldn’t learn to read until you have a very functional knowledge of the language. But in the case of Korean, Hangul is one of the easiest and most perfect writing systems ever developed.

Most people can learn Hangul in about a week, after that, you can read literally anything in Korean. Normally, I tell people to read last, because when you read you have an internal monologue which will be imperfect if you haven’t done sufficient listening first.

What I suggest, to speed up the process, but to also learn the language well, is to buy a university level Korean textbook, and hire a private tutor. Korean teachers will generally want to spend the first several lessons on the alphabet. Don’t let them. Don’t worry about the alphabet for a few weeks. It is probably better to hire a young university student who you can intimidate into teaching you the way you want to learn, as opposed to hiring an experienced teacher who only knows one way and will argue and fight with you.

Have your tutor read the dialogues in your book again and again. At home, listen to the audio CDs for the book. Do not start by having the teacher teach you the symbols or the characters of Hangul. Just follow along with your finger while the teacher reads. Do this for two or three weeks. You will begin to make guesses about what the different characters should sound like. You will begin to recognize words. You will slowly gain a rhythm for the language.

After several weeks, then you could spend a single lesson on the alphabet, to ensure that you know what each letter sounds like and how to recognize them. After that, you can read on your own.

At night, follow the written words on the page while you listen to the CDs. You can start writing at this point. It will help reinforce what you are hearing and learning. But remember, listening is still the key to learning a language and to avoid fossilizing mistakes. Never write an assignment and allow the teacher to take it home and mark it. You go over every assignment, verbally with your teacher, a number of times before you go home and write it. The next day, you should go over your homework verbally, with your teacher. Again, the teacher reads and corrects. You just listen and write. Think about your homework as a talking point, something to help you focus and contextualize your listening.

Don’t speak yet.

What I did with the Korean language was to buy as many level-one textbooks as I could find. There are about three or maybe four series of Korean textbooks sold in Korea. So, I bought all of them. I chose one that I only did with my teacher. The others I did on my own. You can get level one textbooks for free, just ask other foreigners who gave up on learning Korean. They will often pass the books on to you. Just write in them and fill them with ink, writing and rewriting each exercise.

My teacher and I went on like this for about a month or six weeks. Everyday, she read for me. In the evenings I listened to the listening for that book and the listening for the other books which I read on my own.

Eventually, when I started speaking, I only read out my answers from my main textbook while my teacher and I marked my homework.

With Korean language, the listening/speaking is not difficult in the sense of getting the pronunciation right. Actually, Korean, like Mandarin, has only a couple of sounds that we don’t have in English. BUT the listening is difficult because of the complex Korean grammar and registers of speech. So, when you first start “speaking” it should really be just reading grammatically correct and appropriate answers from your book. I did this for hours with my teacher. Occasionally she would ask me something that wasn’t in the book, but I would refuse to answer. You don’t want to start “creating” speech until you are ready. Stick with canned speaking practice for several more weeks.

Finally, you can start speaking. Again, it would be best to wait till the end of 800 hours, but this is not a reality for most people living in the country. So, maybe you start speaking at the end of two months of lessons. My vocabulary was already 2,000 words when I began speaking. And even then, I kept my speaking limited to what was in the book and eventually variations of what was in the book. You should move your reading and listening away from the book and into the real world pretty early on. But your speaking needs to stay in the sterile book world or you will create mistakes that you will never, ever be able to shake.

With all of my languages, once my listening gets to an acceptable level, I encourage people in the real world to talk to me in Korean, but I answer in English. The longer you stay at that level and the more total listening you do, the better your Korean will be when you open up your mouth and start speaking.

If you jump right into speaking, as most teachers want you to do, you will most likely never approach fluency. You will make errors of grammar and appropriateness of speech. Depending upon how early you start speaking you may even make mistakes in pronunciation which is truly sad because Korean is so perfect and easy to pronounce.

The keys to language learning are: dedication, hard work, listening, and discipline to avoid giving in to the temptation to speak too early.

Like Antonio’s writing?

Check out some of his fantastic books on travel, martial arts, language learning and endangered cultures.

]]>

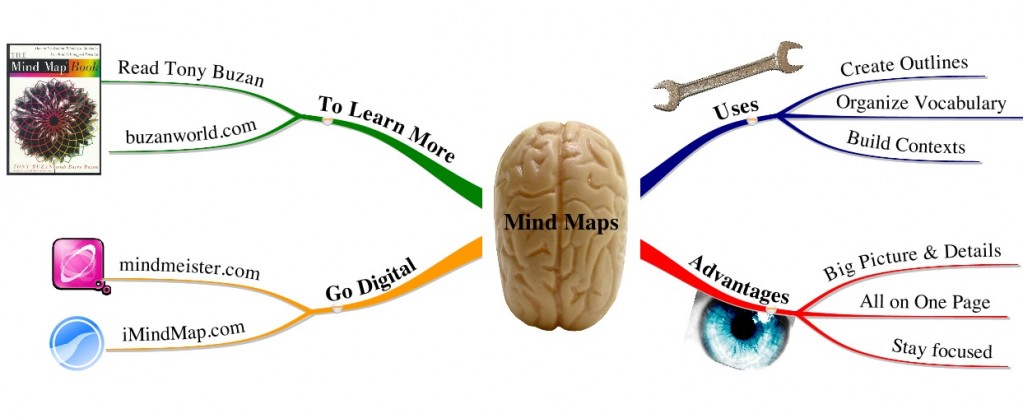

The first thing I’d like to say about mind mapping is how upset I am for not knowing about it sooner! Why wasn’t it taught to me in elementary school, or junior high, or high school, or even university? Why did I labor through so many classes, books and professional or personal challenges without this amazing tool?! Oh well, at least a little angel introduced the concept to me before it was too late… (Thanks Kim!)

So what is mind mapping?

The idea was formalized by British author Tony Buzan. He defines mind maps as follows:

A Mind Map is a powerful graphic technique which provides a universal key to unlock the potential of the brain. It harnesses the full range of cortical skills – word, image, number, logic, rhythm, colour and spatial awareness – in a single, uniquely powerful manner. In so doing, it gives you the freedom to roam the infinite expanses of your brain. The Mind Map can be applied to every aspect of life where improved learning and clearer thinking will enhance human performance.

While I like his definition, I think we can remove the flower pedals and whittle it down to this: A mind map is a non-linear outline. Instead of listing ideas vertically on one or more sheets of paper, you arrange your ideas on one sheet of paper in a web-like structure. It is important to use only one sheet as this forces you to be brief and keep all of the ideas centered around the main idea written in the center. This is a major advantage over using traditional writing which often makes it easy to lose focus on the main idea and get lost in interesting but distracting tangents.

Effective mind maps only use one word or phrase for each topic or sub-topic. This is where many people go astray, adding Twitter-like entries for each bubble. It is difficult to do in the beginning, but training yourself to choose one vivid, concise keyword has many advantages:

- It takes less time to find the information you are looking for

- It takes less time to review the entire mind map

- The keywords will instantly jolt your memory and draw up the desired fact or concept

In addition to keywords, a good mind map makes use of color and images to help stimulate the brain and facilitate fast recall. Don’t worry if you look childish; this is one time when doodling is actually constructive!

How can it be used for language learning?

Mind maps are extremely useful for 3 main purposes in language learning:

- Learning vocabulary

- Building a clear context before, during and after study sessions, classes or conversations with a tutor

- Organizing one’s thoughts before writing

When listening to or reading an article, you can make a mind map that includes all previously unknown vocabulary. Put the title of the article in the center of the map, and then fan the words around the center. You can then add one-word definitions, synonyms, antonyms, parts of speech, translations, drawings, etc. depending on your learning preferencces.

If you are working with your LingQ tutor via Skype, for example, you could both use an online mind map such as Mindmeister. This allows you both to view the same mind map and make changes in real time. The mind map can act as both an agenda for the conversation and a visual tool to aid your listening comprehension. After the call, you can refer back to the mind map to quickly review any new language that came up. If meeting a private teacher or tutor face-to-face, you can accomplish the same thing on paper.

And perhaps the most powerful use of mind maps is organizing your thoughts before you begin writing. Here are some of the benefits of mind mapping first:

- Greatly reduced writer’s block in both your native and foreign languages. An initial time investment of 10 to 20 minutes often saves hours of lost time thinking about what to write next and second guessing and changing what you have already written.

- Keeping focused on both the big picture and relevant details without getting lost in minutiae. If you just start writing paragraphs, it is easy to forget the main idea you presented in the introduction whilst filling out the details of supporting paragraphs. But if you have a mind map to refer back to you, you can quickly and easily check the relevancy of what you are typing.

Take Action

- Download a free trial version of iMindMap here (this is the program I used to create the mindmap shown above.

- Or, set up a MindMeister account so you can use online, collaborative mind maps with your tutor. You can visit their site by clicking this image:

- Read any of Tony Buzan’s books on mind mapping and improving memory. I’ve read them all; each one is a wonderful treasure chest of useful tips and knowledge: