Antonio Graceffo is an applied linguist, and martial arts and adventure author living in Asia (check out our interview with him here). His books, including ”The Monk from Brooklyn”, are available at Amazon.com .

.

Googling around the internet I found a lot of sites where people had written in saying, “I am studying language XYZ, and I want to know how many words I have to know to be able to read a newspaper.”

Googling around the internet I found a lot of sites where people had written in saying, “I am studying language XYZ, and I want to know how many words I have to know to be able to read a newspaper.”

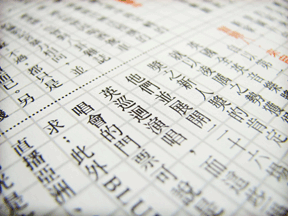

This question is particularly relevant for people who are studying Chinese, where each word is a character, and most students know the exact number of characters that they can read. Whereas students who have been studying Spanish, German, or Vietnamese for a period of years, wouldn’t generally know the exact number, or may not even know an approximate number of words that they understand.

This information is relevant for anyone studying a foreign language, including English, particularly if your goal is to study at a university overseas or to work in a professional job in the foreign language environment.

Checking a number of websites, the answers varied substantially.

On aksville.com, someone took the time to write a long reply, explaining that major newspapers, such as USA Today, are written at a 6th to 8th grade level and require approximately 3,000 words to read.

Another site, called blogonebytes.com: “I read somewhere that to be able to carry on a good conversation in “Mandarin Chinese” one should know about 3,000 characters, and about 7,000 characters to read technical books.”

A follow up comment by a reader on the same site said, “You will need to know a minimum of 3000 characters to be proficient. You will need to be able to speak and understand in the range of 5000-7000 characters.”

According to Omniglot, a site which I tend to have a lot of respect for, “The largest Chinese dictionaries include about 56,000 characters, but most of them are archaic, obscure or rare variant forms. Knowledge of about 3,000 characters enables you to read about 99% of the characters used in Chinese newspapers and magazines. To read Chinese literature, technical writings or Classical Chinese though, you need to be familiar with at least 6,000 characters.”

I had always heard that the range was somewhere between 1,500 and 3,000 words to read a newspaper. In the case of Chinese, I know that I can read right about 3,000 characters, and yet, I absolutely cannot read a newspaper. If you hand me a newspaper, I can pick out words that I know, but I can’t actually read and understand the stories.

In Bangkok, I have several friends who are extremely conversant in Thai, and they can read a menu. But they would need an entire day and a dictionary to read a single newspaper story. And even then, they wouldn’t understand everything.

With German, after four years of studying and working as a translator and researcher in the country, I can obviously read anything. But, I have no idea how many words I know. Now that I am embarking on my study of Bahasa Malay, and also making plans to go back and finish learning Vietnamese, I am becoming very curious how long it will take to get my reading level anywhere close to what it is in English or Spanish. My own experience with Chinese made me question this 3,000 word figure. Also, as a person who earns most of his living from writing for magazines, newspapers, and books, I would hate to believe that I only write a 3,000 word vocabulary , and on a 6th to 8th grade level.

As many times as I attended 9th grade, you would think I would be writing at least at high school level.

The two facts that I wanted to verify were, the average reading level of The New York Times, my hometown paper, and the average number of words per edition.

The first question was easy to answer.

The May 2, 2005 edition of “Plain Language At Work Newsletter”, Published by Impact Information Plain-Language Services, explained that there are two generally accepted scales for determining the reading level of various publications. They are the Rudolph Flesch Magazine Chart (1949) and the Robert Gunning Magazine Chart (1952). Both charts analyzed such aspects of a magazine or newspaper such as, average sentence length in words and number of syllables per 100 words. Based on this information, they assigned a school grade reading-level to the publication. According to this rating system, The Times of India was considered the most difficult newspaper in the world, with a reading level of 15th grade. The London Times scored a 12th grade reading level, as did the LA Times and the Boston Globe. The survey must have been flawed, however, because they assigned The New York Times a reading level of 10th grade, which is lower than the LA Times, when everyone knows quite well that New York is better than California or any other place which is not New York.

If you get most of your news from Time Magazine, you might be pleased to know that Time and TV Guide both scored a 9th grade reading level.

The survey didn’t cover newspapers written in languages other than English, but if we assume that we are shooting for an average 10th grade level, this will probably be close to what you need to read a newspaper in any language.

The next question was much harder to answer. How many words do I need to read the New York Times? I have never believed the low estimates of 3,000 or less, simply because every event that happens anywhere in the world, any human situation can appear in the Times as a news story and could of course, require the appropriate vocabulary.

To answer the question, I went to the June 4, 2010 New York Times online and I chose 8 articles, taken from several different sections, because I assumed they would all require different vocabulary. The stories were: “Pelicans, Back From Brink of Extinction, Face Oil Threat”, “BP Funneling Some of Leak to the Surface”, “John Wooden, Who Built Incomparable Dynasty at U.C.L.A., Dies at 99”, “An Appraisal : Wooden as a Teacher: The First Lesson Was Shoelaces”, “Should you be able to discharge student loans into bankruptcy?”, “On the Road to Rock, Fueled by Excess” as well as other tidbits, announcements and follow up articles.

In some cases, if the articles were very long, I didn’t take them in their entirety, assuming there would be much repetition of words.

In all, I took parts of about 8 stories, comprising 51 pages of text. The stories I took didn’t even represent 10% of the total content of this particular edition of The New York Time, June 4, 2010 online edition.

I pasted the words into a word document, converted them to a single column table, which ran over 450 pages long. Then I sorted the table alphabetically. Up to this point, it was easy, just pressing buttons. Next, I had to go through all 450 pages, all 10s of thousands of words, removing duplicates. It was one of the most tedious exercises I have ever conducted in my life. It was exactly the type of obsessive compulsive behavior that gets people locked up in mental institutions. It took 16 hours. By the 10th hour, I began hallucinating. Nearing the 12th hour, I believed I was a hummingbird of some kind.

I allowed plural forms of nouns, so I counted “car” once and “cars” once. I also included all forms of a verb, so “walk” once, “walked” once, and “walking” once. I counted proper nouns, including place names, as the names of people and countries will come up in the news and you need to know them. Also, in foreign language, particularly Asian languages, the grammatical forms and proper names may not even be recognizable if you haven’t studied and learned them.

When I was finished, I found that the random sampling of stories I chose contained 4,139 unique words. This was much higher than the estimates I had read on some websites, but was well in line with what I suspected. If I had the energy to complete a similar analysis of the entire edition, I would have to believe the number would increase. And if we monitored the newspaper over a period of one month, analyzing the text every day, and comparing the vocabulary against an accumulated list, I would imagine that it would grow. Most likely the difference in vocabulary from day to day would be small, but still, the necessary vocabulary would increase.

Comparing the dialogues in my Chinese textbooks with the vocabulary that appeared in these New York Times articles, much of what I learned in school was useless. For example, all foreign language textbooks have chapters devoted to shopping at the market, where you have to memorize tedious lists of Fruits and vegetables. In these Times articles, not a single fruit name was mentioned. Neither my Vietnamese, Chinese, or Bahasa textbooks include the names of heads of state of various countries. But obviously, these names came up in world news stories.

Below is a small sampling of words that I found in the news story which, I don’t know how to say in Chinese. Some of these words, I question, however, if the average 9th grader would know them. Do 9th graders know: abetted, absinthe, archeo-feminist, or bearish?

abetted albeit assesses bankruptcy biofuels able-bodied. Amandine assessment batch biography abortions ambivalent assets bawdy-sweet black-clad absinthe anachronistic asthmatic bearish bleak absurd. anarchic audience-pleasing Bedford blemish accord Appended aura befriended blockade across-the-board Archbishop autobiography behind-the-back blowout activists archeo-feminist autograph-seekers benefits bond Advocates articulate awfully best-selling booster aerodynamic assertion babbles bioenergy breakthrough

Names and proper nouns are important for understanding news stories. In language textbooks you may learn the names of major countries and the capital cities, but news happens in small cities and even villages as well. To read the news you need to know the names of political parties, famous people, economic theories, financial indices, global corporations, educational institutions, associations, and international organizations such as the UN.

All of these names were taken from the same collection of stories. Do you know how to say these in Vietnamese or write them in Thai?

Cypriot Delta Geneva Mediterranean Bihar Baltic Democrat Greece Nehru Turkish-controlled Brooklyn Denmark Uttar Metropolitan Nasdaq Iranian Dow Midwesterner Mayor Polytechnique Louisiana Durbin Scotch Reich Iskenderun. pro-Greek Dutch-Irish Rev. Latino Kentucky. California Baptist BENJAMIN Bonaventure/Agence Burke/Associated Cambridge Chicago-based Berkeley Pennsylvania. Bush Cyprus Barataria-Terrebonne Navy BP Dallas-Fort Audubon Gandhi. Bess Dalit Arce

How many of the above terms were you able to translate or transliterate into the language that you study? This is the level of reading that an adult native-speaker can do, and this should be your goal. If the task doesn’t seem daunting enough, remember, in this article, we were only concerned with vocabulary. But you could have a vocabulary of a million words not be able to understand a newspaper or a book. For real communication, you need a comprehensive approach to language, which includes culture, syntax, context, and grammar.

It’s a long stretch. I know. And it can seem impossible. But remember, every Sunday in New York City Catholic mass is said in 29 languages. For more than a century, large numbers of immigrants, my family included, have been coming to America and Canada in search of a better life. Most of them learned English with less than half of the education of the average person reading this article.

So, if your Grandma and Grandpa could learn a new language to a level of functionality, so can you.

Like Antonio’s writing?

Check out some of his fantastic books on travel, martial arts, language learning and endangered cultures.

]]>

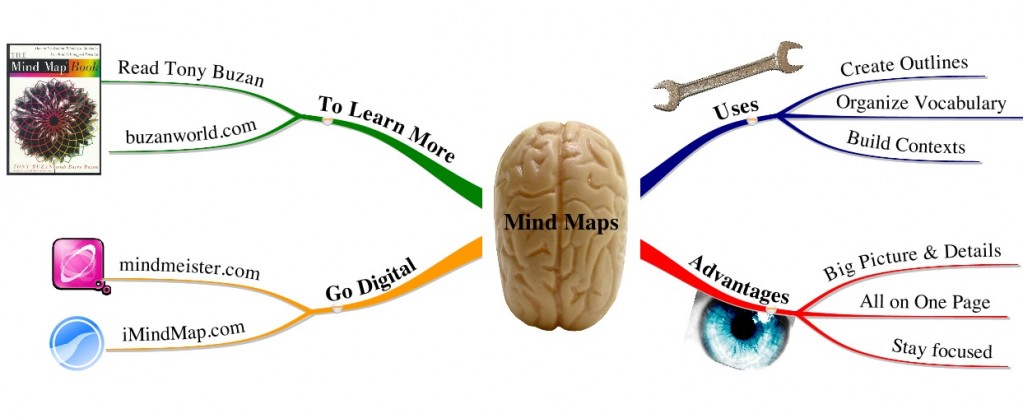

The first thing I’d like to say about mind mapping is how upset I am for not knowing about it sooner! Why wasn’t it taught to me in elementary school, or junior high, or high school, or even university? Why did I labor through so many classes, books and professional or personal challenges without this amazing tool?! Oh well, at least a little angel introduced the concept to me before it was too late… (Thanks Kim!)

So what is mind mapping?

The idea was formalized by British author Tony Buzan. He defines mind maps as follows:

A Mind Map is a powerful graphic technique which provides a universal key to unlock the potential of the brain. It harnesses the full range of cortical skills – word, image, number, logic, rhythm, colour and spatial awareness – in a single, uniquely powerful manner. In so doing, it gives you the freedom to roam the infinite expanses of your brain. The Mind Map can be applied to every aspect of life where improved learning and clearer thinking will enhance human performance.

While I like his definition, I think we can remove the flower pedals and whittle it down to this: A mind map is a non-linear outline. Instead of listing ideas vertically on one or more sheets of paper, you arrange your ideas on one sheet of paper in a web-like structure. It is important to use only one sheet as this forces you to be brief and keep all of the ideas centered around the main idea written in the center. This is a major advantage over using traditional writing which often makes it easy to lose focus on the main idea and get lost in interesting but distracting tangents.

Effective mind maps only use one word or phrase for each topic or sub-topic. This is where many people go astray, adding Twitter-like entries for each bubble. It is difficult to do in the beginning, but training yourself to choose one vivid, concise keyword has many advantages:

- It takes less time to find the information you are looking for

- It takes less time to review the entire mind map

- The keywords will instantly jolt your memory and draw up the desired fact or concept

In addition to keywords, a good mind map makes use of color and images to help stimulate the brain and facilitate fast recall. Don’t worry if you look childish; this is one time when doodling is actually constructive!

How can it be used for language learning?

Mind maps are extremely useful for 3 main purposes in language learning:

- Learning vocabulary

- Building a clear context before, during and after study sessions, classes or conversations with a tutor

- Organizing one’s thoughts before writing

When listening to or reading an article, you can make a mind map that includes all previously unknown vocabulary. Put the title of the article in the center of the map, and then fan the words around the center. You can then add one-word definitions, synonyms, antonyms, parts of speech, translations, drawings, etc. depending on your learning preferencces.

If you are working with your LingQ tutor via Skype, for example, you could both use an online mind map such as Mindmeister. This allows you both to view the same mind map and make changes in real time. The mind map can act as both an agenda for the conversation and a visual tool to aid your listening comprehension. After the call, you can refer back to the mind map to quickly review any new language that came up. If meeting a private teacher or tutor face-to-face, you can accomplish the same thing on paper.

And perhaps the most powerful use of mind maps is organizing your thoughts before you begin writing. Here are some of the benefits of mind mapping first:

- Greatly reduced writer’s block in both your native and foreign languages. An initial time investment of 10 to 20 minutes often saves hours of lost time thinking about what to write next and second guessing and changing what you have already written.

- Keeping focused on both the big picture and relevant details without getting lost in minutiae. If you just start writing paragraphs, it is easy to forget the main idea you presented in the introduction whilst filling out the details of supporting paragraphs. But if you have a mind map to refer back to you, you can quickly and easily check the relevancy of what you are typing.

Take Action

- Download a free trial version of iMindMap here (this is the program I used to create the mindmap shown above.

- Or, set up a MindMeister account so you can use online, collaborative mind maps with your tutor. You can visit their site by clicking this image:

- Read any of Tony Buzan’s books on mind mapping and improving memory. I’ve read them all; each one is a wonderful treasure chest of useful tips and knowledge: