by John Fotheringham

Just as the printing press democratized access to the written word, ebooks are again revolutionizing how information is produced, distributed and consumed. Even successful authors, whose very livelihoods have depended on the sale of dead-tree books (e.g. Timothy Ferriss, author of The 4-Hour Workweek and The Four-Hour Body, and Seth Godin, author of Tribes, Permission Marketing, and All Marketers are Liars) have seen the writing on the literary wall, and agree that “print is dead”, or at least “dying fast”…

Here are a few reasons why the ebook is beating print books to a “pulp” (pun intended):

- Lower Production & Distribution Costs: This allows for lower retail prices, putting books in the hands of more and more readers. And many ebooks are available at no cost at all, including literary classics no longer covered by copyright (e.g. Project Gutenberg) and new works that are free by choice (this is one of the common “freemium” strategies where an ebook is used for free marketing to promote other paid content or services.)

- Read Anytime, Anywhere: You can literally carry thousands of ebooks with you on your mobile device or ebook reader. Language learning is then just a click away whether you are on the bus, a plane, or bored to tears in a meeting. And if you forgot to download books at home, you can always download more on the go via WiFi or even 3G networks.

- More Time Efficient: Many ebook readers allow you to easily cut and paste words and even look up unknown terms using built in dictionaries. This can save the learner hours and hours, especially in ideographic languages that usually require looking up characters by strokes, radicals, or handwritten input.

So now that I’ve made the case for ebooks, let’s look at my two favorite weapons of choice for using ebooks in foreign language learning:

Best Ebook Readers

There are heaps of ebook reader devices on the market today (the Amazon Kindle, the iPad, the Sony PRS series, the Barnes & Noble Nook, etc.), as well as numerous ebook reader apps available for Android devices, iPhones, iPads, iPod touches, Blackberry devices, PCs and Macs. After trying out hundreds of different devices at last year’s CES and stealing…I mean “borrowing”…a few of my friend’s devices for further testing, here are my two finalists:

1st Place: The Amazon Kindle 3G

1st Place: The Amazon Kindle 3G

Price:

- Kindle 3G: $189 USD

- Kindle (WiFi version): $139 USD

Where to get ‘em: Available from Amazon.com

While I am a full-fledged Apple fanboy, I must give Amazon credit where credit is due. Despite serious competition from the Apple iPad, Sony’s various ebook readers, and myriad other me-too products, the Kindle remains a hot seller, and my humble opinion, the world’s best ebook reader.

Here’s what I love most about the Kindle:

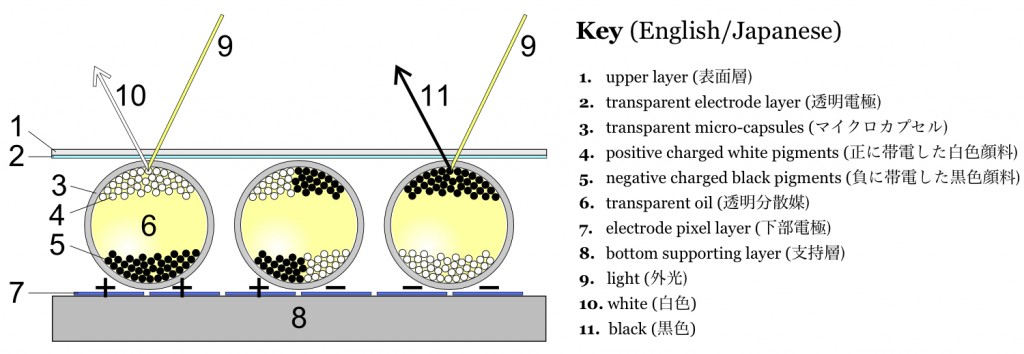

1) E ink is easy on the eyes and your battery. Unlike the pixels used on computers and smartphones (which can wreak havoc on your eyes and zap your battery), the Kindle’s use of E Ink creates a reading experience pretty darn close to physical books, all while consuming very little battery life. They accomplish this amazing feat by employing millions of itsy-bitsy, electronically charged “microcapsules”, within which there are tons of little black pigment pieces and white (or rather, light gray) pigment pieces. Text is produced by causing the black pigments to run to the top of specific microcapsules, while the background is created when the gray pigment is forced to the top. The Kindle display is also much easier to read outside in the sun, while most other devices (including the iPad, iPhone, and iPod touch) suffer from serious glare problems.

2) Direct access to the world’s largest book store pretty much anywhere in the world. Users can wirelessly access over 750,000 ebooks, plus heaps of audiobooks, newspapers, magazines and blogs, in over 100 countries worldwide. And unlike the iPad, the 3G wireless connectivity is provided free of charge.

3) Great Apple and Android apps. If you don’t want to fork over the funds for a Kindle, or you already own one but don’t feel like lugging it around all the time, you can always just download the Kindle app.

Download the free Kindle app (Android, Apple iPhone, iPad, iPod touch, Blackberry, PC, or Mac)

2nd Place: iBooks on the Apple iPad, iPhone & iPod touch

Prices:

- iBooks: free download in iTunes

- iPod touch: $229 USD (8GB), $299 (32GB), and $399 (64GB)

- iPad (WiFi): $499 USD (16GB), $599 USD (32GB), and $699 USD (64GB)

- iPad (3G): $629 USD (16GB), $729 USD (32GB), and $829 USD (64GB)

Where to get ‘em: Apple retail stores, the Apple Online Store, Amazon, Target, WallMart, AT&T Stores, Verizon Stores (iPad is available now; iPhones will allegedly be available through Verizon in early 2011…).

1) More than JUST an ebook reader. My only gripe with the Kindle is that it is only an ebook reader. With the iPad, iPhone, or iPod touch, on the other hand, your device is only limited by the apps you download to it. I currently have about 100 hundred apps on my iPod touch, including Skype for calling tutors and language partners, Evernote for keeping notes of new words and phrases, iLingQ, ChinesePod, SpanishPod, and on, and on, and on…

2) Sexy, intuitive user interface. The Kindle interface isn’t bad by any measure, but it pales in comparison to the rich, elegant design of Apple iBooks. The new “retina display”, available on the iPhone 4, iPod touches (4th gen), and likely the next vesion of the iPad, creates extremely crisp, vivid images, and makes reading text far easier than on lower resolution devices.

3) Excellent built in dictionary, bookmarks, highlighting and search features. iBook’s built in dictionary, bookmarks and highlighting tools are a thing of beauty. To look up a term, you need simply tap the word and then click “Dictionary” from the pop-up menu. To highlight, you again just tap a word and then drag the handles to the left or right to select the words or sentences you want. Bookmarking requires just a quick tap in the upper right corner. Best of all, you can then quickly go back to your saved highlights or bookmarks using the table of contents tab. Also, you can use the search feature to quickly find all instances of a particular word (a very useful feature for language learners as it allows you to quickly see how a particular word is used in context.)

Getting the Most Out of Ebook Readers

As we’ve seen, ebooks and ebook readers are wonderful language learning tools indeed. But as ESLpod’s Dr. Jeff McQuillan puts it, “A fool with a tool is still a fool.” Here then, are some tips on how to best apply these amazing new tools.

1) Don’t fall into the trap of reading more than you listen. Reading is an important part of language acquisition, and is an essential component of learning how to write well in a foreign language. But remember that listening and speaking should be the focus of language study, especially in the early stages of learning. It is all too easy to spend too more time with your nose in a book than listening to and communicating with native speakers, especially for introverts and those who have been studying for too long with traditional, grammar and translation based approaches.

2) Read an entire page before looking up unknown words. Lest you get distracted and lost in the details, I suggest making at least one full pass through each page in your ebook before looking up unfamiliar words.

3) Choose books that are just a tad beyond your comprehension level. By “comprehensible” I mean that you can understand about 70 to 85% of the text. Too far above or below this and you will quickly get bored and likely give up.

4) Use the Kindle’s Text-to-Speech Tool. The Kindle and Kindle 3G can literally read English-language content out loud to you. Use this feature when you are doing other tasks that require your vision but not your ears, and as a way of building your listening comprehension. I suggest listening to a passage first and then reading to back up your comprehension.

5) Get audio book versions of ebooks you read. While the Kindle’s text-to-speech tool works well, it can get a bit monotonous with its robotic pronunciation. For longer books, I suggest buying the audio book version the book, which tend to be read by professional voice actors, and are therefore far easier to listen to… Audio books are available from Audible, iTunes, and countless other site, and make sure to check out the free Audiobooks app for the iPhone, iPad and iPod touch.

]]>

As a language learning addict, I follow lots (and I mean lots) of polyglot blogs and podcasts. It is always interesting to see what has worked (and what hasn’t worked) for successful language learners. While most fluent foreign language speakers tend to agree on the vast majority of language learning DOs and DON’Ts, there is one area that always seems to cause heated debate, shouting, name calling, and occasional mud/poo flinging: the importance of language input (i.e. listening and reading) versus language output (i.e. speaking and writing).

I have sat quietly on the sidelines for some time now, politely listening to both sides of the argument. But it’s time to blow my referee whistle because both teams are “offsides” (Okay John, enough sports analogies already!)

The Argument is Flawed to Begin With…

The problem with the whole argument is that input and output are not mutually exclusive components of language learning. You need both. The key is order and balance.

1. Listen first, then speak

When just starting out in a language, it is important to get as much listening input as possible. Just like when you learned your first language, you need to first go through a “silent period” where your brain gets used to the patterns and phonology of the language. Once you have filled your teapot up with enough listening input, language will naturally want to start pouring out. That’s when it’s time for a tea party to put into practice what you have assimilated (and no, I am not promoting that kind of “tea party” as I am a bleeding-heart liberal…)

When just starting out in a language, it is important to get as much listening input as possible. Just like when you learned your first language, you need to first go through a “silent period” where your brain gets used to the patterns and phonology of the language. Once you have filled your teapot up with enough listening input, language will naturally want to start pouring out. That’s when it’s time for a tea party to put into practice what you have assimilated (and no, I am not promoting that kind of “tea party” as I am a bleeding-heart liberal…)

But unlike little babies, adults can also rely on reading input to back up what we listen to. This difference (along with the fact we don’t have to wear diapers) gives adults a major leg up on babies learning their first language.

To this end, try to find short, simple dialogues of actual native speakers with transcripts. Then listen and read, listen and read, and listen and read again as many times as your schedule and sanity allow. My personal favorite transcript-equipped podcasts are produced by Praxis Language (ChinesePod

, SpanishPod

, FrenchPod

, ItalianPod

and EnglishPod

) and LingQ (English, French, Russian, Spanish, German, Portuguese, Italian, Korean, Chinese, Japanese, and Swedish). I can’t stand the overly stilted, monotonous dialogues found on most textbook companion CDs and suggest you avoid them like the plague.

2. Take equal doses of your input and output medicine.

Once you have gone through your silent period (which will be input-centric by definition), try to spend an equal amount of time on input activities (listening to podcasts, reading blogs, etc.) and output activities (speaking with friends or tutors, writing a blog post in the foreign language, etc.). It may be nerdy, but I literally use the stop-watch feature on my iPod touch to time my input and output activities each day…

If you follow the above regimen, your foreign language skills will progress quickly, efficiently, and most importantly, enjoyably. However, if you follow the advice of the extremists on either side of the input-output debate, you are in for heaps of problems and a world of pain. Here’s why:

Output Only Problems

Proponents of the “Output is awesome; input is lame” philosophy suggest that learners just “get out there and start communicating with native speakers”. This approach, while certainly sexier than what I prescribe above, has a number of problems:

1. Nasty mispronunciation habits.

Bad pronunciation habits develop when you pronounce things how you think they should be pronounced based on your overly limited listening exposure to the language, and your logical, but nonetheless incorrect, assumptions based on how words are spelled but not pronounced.

2. You’ll be that annoying guy at the bar.

Because you have a limited vocabulary and only understand little of what is said to you, you will likely attempt to control conversations by keeping them on topics you are familiar with, using phrases and vocabulary you have memorized. All but the most patient interlocutors will get bored or annoyed by such one-sided conversations. Don’t be that guy.

3. You probably won’t enjoy the process and give up early.

Many would-be language learners give up because they simply don’t enjoy the process. Much of the angst, tedium and phobias stem from having to speak before one is ready. Language teachers are the worst perpetrators, presenting you with new words or phrases one minute, and then expecting you to actually use them the next. Well-meaning friends or language partners are no better, trying to “teach” you new words and phrases and expecting that you can actually use them right away. Assimilation takes time and repetition, so don’t beat yourself up if it takes a few times (or a few hundred times) of hearing or reading a new word or phrase before you can actually use it.

Input Only Problems

If, however, you spend months and months diligently listening to your iPod and reading online newspapers, but never actually speaking with native speakers (by design or chance), you will understand quite a bit of what goes on around you but will struggle to actually verbalize your thoughts well or have natural exchanges with native speakers. This happens because:

1. Proper pronunciation is a physical feat.

You can’t think your way through pronunciation (believe me, most introverts have tried and failed!). Good pronunciation requires that your ears first get used to the new language (i.e. through getting lots and lots of listening input), and then also getting your lips, tongue and larynx used to new sounds not found in your native tongue, which of course takes lots and lots of talkin’ the talk.

2. Speaking and writing identifies your learning gaps.

Until you actually try to say or write something, you won’t know what you really know. While you may passively recognize certain words, phrases, idioms or Chinese characters, you may still struggle to say or write them. This is even true for your native language (as I found out when I first started teaching English and was confronted with such conundrums up at the white board as “Wait a second…How in the hell do you spell “misspelled”?)

The more you speak and write, the more you know where the “holes” are in your language cheese, and the easier it will be to fill them with focused study and review.

Conclusion

So as in all things, the extremists tend to be just that: extreme. They tend to get more attention, but the efficacy of their advice tends to be an inverse proportion to their popularity…

To become fluent in a language, just consume a balanced diet, rich in listening and speaking, with plenty of reading and writing sprinkled in for flavor.

]]>Antonio Graceffo is an applied linguist and martial arts and adventure author living in Asia (check out our interview with him here). His books, including ”The Monk from Brooklyn”, are available at Amazon.com .

.

A Khmer student wrote to me on youtube and asked me to produce videos about how to read English language newspapers.

A Khmer student wrote to me on youtube and asked me to produce videos about how to read English language newspapers.

“I’d like to ask you to make videos how to read newspaper and translate it from English to Khmer. I Khmer and I having a problem to understand English phrases.” Wrote the student.

Language learners often write telling me about some area of learning or area of their lives where they are experiencing difficulties of comprehension and ask me for a trick or a guide to help them learn.

As I have said in numerous other language learning articles, there are no tricks and no hints. The more hours you invest, the better you will get. And if your goal is to read at a native speaker level, then you need to read things a native speaker reads. If you are a 22 year-old university graduate, then you need to be reading at that level in the foreign language. And you won’t get there by reading textbooks ABOUT the language. You will get there by reading books, articles, and textbooks IN rather than ABOUT the language.

If we analyze this latest email, the student says he has trouble reading, and he specifically singled out newspapers.

Obviously, reading is reading. On some level, reading a newspaper is no different than reading a novel or reading a short story.

If you are reading novels and short stories, you should be able to read newspapers. If I asked this student, however, he is probably is not reading one novel per month in English. If he were, newspaper reading would just come.

Therefore, the problem is not the reading or the newspapers, per se. The problem is the lack of practice.

I never took a course called “Newspaper Reading” in English. I just started reading newspapers. And at first, I had to learn to deal with the language, structure and organization of newspaper writing, but no one taught me, or you. It just came to us. The same was true for German or Spanish newspapers which I can read almost as well as English. No one taught me, or taught Gunther or Pablo, it just came through practice.

A point, that I have made many times in articles, is that when you begin learning a foreign language, you are not an idiot. You are not starting with an empty brain. One reason it takes babies three years to learn their native tongue is because they are also learning what a language is and how language works. You know all of that, and much more. Babies don’t know that there is such a thing as grammar. Every single piece of vocabulary has to be learned. A seven year old may not know the words “population, economy, government, referendum, currency” in his native tongue. So, reading a foreign newspaper would be difficult for him, because reading a newspaper in his mother tongue is difficult for him.

If you are an adult, coming from a developed country, with at least a high school or university level of education, you should already be able to read newspapers in your native tongue. At that point, reading a newspaper in a foreign tongue is simply a matter of vocabulary.

True there are different uses of language, and styles of writing. And newspapers do have style which differs from other kinds of writing. But you just read, and read and figure them out.

The problem with most learners, however, is that they aren’t reading novels and short stories. Most learners need to just accept that they need practice. They need to read, and read, and stumble, and fall, and read again, until they get it.

I didn’t develop a taste for reading the newspaper in English untill I was in my late twenties. But, by that time I had read countless books in English, and completed 16 years of education. I only began reading newspapers because I had to read foreign newspapers at college. Then I learned to read the newspapers in English first, to help me understand the foreign newspaper.

One of the problems, specifically with Khmer learners is that there is so little written material available in Khmer. American students have had exposure to newspapers, magazines, novels, reference books, poetry, plays, encyclopedias, diaries, biographies, textbooks, comic books… Most Khmers haven’t had this exposure.

If they haven’t read it in their native tongue, how could they read it in a foreign language?

And, I am not just picking on Khmers. True these styles of writing are not available in Khmer language, but even in Chinese, Korean, or Vietnamese education, where these many styles of writing exist, students may not have had exposure to them. For example, Taiwanese college students said that during 12 years of primary school they never wrote a single research paper.

But then they were asked to do that in English, in their ESL classes.

Currently, I have a Thai friend, named Em, who is studying in USA. He has been there for three years, studying English full time, and still can’t score high enough on his TOEFL exam to enter an American community college. In Thailand he is a college graduate, but education in Thailand is way behind western education. And in the developed world, American community colleges are about the single easiest schools of higher learning to enter.

If Em finally passes the TOEFL and gets into community college, in the first two years of core requirements for an American Bachelor’s Degree, he will be given assignments such as “Read George Orwell’s 1984, and explain how it is an allegory for communism, and how it applies to the Homeland Security Act in the US.”

When foreign students stumble on an assignment like this, they always blame their English level. But I am confident that the average graduate from most Asian countries couldn’t do this assignment in his native tongue. Their curriculum just doesn’t include these types of analytical book reports.

When I was teaching in Korea, there was a famous story circulating around the sober ESL community. A Korean girl, from a wealthy family, had won a national English contest. She had been tutored by an expensive home teacher, almost since birth, and her English level was exceptional. The prize was a scholarship to a prestigious boarding school in the Unites States, graduation from which almost guaranteed admission to an Ivy League school.

Apparently, one of the first assignments she was given at her new school in America was to read a poem and write an original analysis of it, and then give a presentation in class. When it came time for her presentation, the student stood up and dutifully recited the poem, word for word, she also regurgitated, exactly, what the lecturer had said about the poem in class. And she failed.

In Korea, her incredible memory and ability to accurately repeat what the teacher had said, had kept her at the top of her class. But in America, she was being asked to do much more than that; think, and analyze, create, present, and defend.

The majority of learners believe that their difficulty in dealing with foreign education, books, newspapers, or conversations lies in their lack of vocabulary or failings of language. But once they posses a relatively large vocabulary, the real problem is some combination of culture and practice.

Getting back to the Khmer student and his problem reading English newspapers: To understand English newspapers you also have to know all of the news and concepts in the newspaper. The best way to deal with foreign newspapers, at the beginning, is to first read a news story in your own language. Then read the same news story in the foreign language newspaper. Also you can watch the news in your own language and then in whatever language you are studying, and compare.

Translation isn’t just about knowing words. You have to know concepts. The first rule of translation is that the written text must convey the same meaning in the target language as it did in the source language. Even if the wording, in the end, is not even remotely like the original. No matter how good your foreign language skills are, you cannot convey meaning which you don’t know in your native tongue.

Recently, newspapers in Asia were running stories about the Taiwan Y2K crisis.

To understand the newspaper stories, you would first need to understand the original, global Y2K crisis. The global Y2K issue was something that Cambodia wasn’t very involved in because there were so few computers in Cambodia in the year 1999. There were probably less than one hundred or so internet connections in Cambodia at that time. Next, you would have to know and understand that Taiwan has its own calendar, based on the founding of the Republic of China in 1911. Government offices and banks in Taiwan record events according to the Republic of China calendar, which means if you take money out of an ATM machine today, the year will show as 99.

Once you know and understand these facts, then you would know that Taiwan is about to reach its first century, in the year 2011, and is facing a mini-Y2K crisis, because the year portion of the date in the computer only has two digits.

The bulk of my readers do not live in Asia, and may not have known anything about the history of Taiwan, or the Taiwan date. But, any person with a normal reading level should have understood my explanation. It is not necessarily a requirement that you posses prior knowledge of the exact situation you are reading about, but you can relate it to other things you know about, for example, other calendars and otherY2K problems.

If you look at the above explanation, the vocabulary is fairly simple. There are probably only a small handful of words, perhaps five or six, which an intermediate language learner wouldn’t know. So, those words could be looked up in a dictionary. And for a European student, with a broad base of education and experience, that would be all of the help he would need. But for students coming from the education systems of Asia, particularly form Cambodia which is just now participating in global events such as the Olympic Games for the first time, it would be difficult, even impossible, to understand this or similar newspaper stories.

The key lies in general education, not English lessons. Students need to read constantly and simply build their general education, in their own language first, then in English, or else they will never understand English newspapers or TV shows.

]]> The Polyglot Project is a new online reading tool with pop-up translations when you double click on words. The site is still in its infancy, but holds a lot of promise if they continue to expand their library and languages as their website promises.

The Polyglot Project is a new online reading tool with pop-up translations when you double click on words. The site is still in its infancy, but holds a lot of promise if they continue to expand their library and languages as their website promises.

As always, here are the pros and cons of the site as I see them:

The Good

It’s free & easy to sign up: As it stands, the site is completely free and it only requires you to fill in an email, password and your native language. That’s it.

Intuitive, easy to use design: Once you’re logged in, you just pick a book from the library, and begin reading. To look up a word, simply double-click on it and the translation in your native tongue will pop-up briefly.

Navigation shortcuts: Instead of clicking the next or back arrows, you cut just press the “n” or “p” keys for “next” and “previous” respectively.

Simple pop-ups: Many dictionary pop-up systems show too much information, which not only slows down the interface, but also slows down you the learner. There is no chance to get lost or distracted as The Polyglot Project only flashes a single word translation for a short time.

System memory: The system automatically adds any books or languages you’ve browsed to your account dashboard so you can quickly jump back to what you were previously reading. You can of course delete books or languages you no longer wish to view.

The Bad

Limited titles: So far, there are only a few titles available on the site, and they are all literary classics. I like the classics just as much as anyone, but they probably aren’t the best choice for someone just starting out in a language. For starters, they tend to use archaic vocabulary and structures no longer used in the modern language (which is of little use for someone trying to communicate with native speakers. I much prefer getting a firm handle on the modern language before delving into the classics. I hope they will soon add some modern fiction and non-fiction to the mix.

Limited languages: So far, the site only offers four Indo-European languages: German, Spanish, Italian and French. As an Asiaphile, I would greatly like to see Chinese, Japanese, and Korean join the list, as well as other top-ten, must-learn languages like Arabic. I understand, however, that each of these languages poses serious technical challenges: since they don’t naturally include spacing between words, it makes it hard for pop-up dictionaries to parse between different terms.

No way to save vocabulary: In its current design, there is no way to save and then later review words you have looked up. This is my favorite part of using sites like LingQ and I have come to expect it in foreign language reading sites.

Reading only: Reading is a wonderful tool for improving your vocabulary and writing skills, but it should take a back seat to (or at least be supplemented by an equal portion of) listening. This is especially true when you just start out in a foreign language. Many language learners spend far too much time reading and not enough time listening, leading to big vocabularies and strong reading and writing skills, but often causing poor listening skills and strange pronunciation patterns (i.e. they say words how they think they are pronounced based on reading, not how native speakers actually pronounce them).

The Verdict

The Polyglot Project is definitely worth checking out, and acts as a good supplement to your other foreign language learning activities. If they are able to expand their library with modern books and additional languages, they will have created a very powerful language tool, and will likely attract a strong following.

]]>Antonio Graceffo is an applied linguist, and martial arts and adventure author living in Asia (check out our interview with him here). His books, including ”The Monk from Brooklyn”, are available at Amazon.com .

.

Googling around the internet I found a lot of sites where people had written in saying, “I am studying language XYZ, and I want to know how many words I have to know to be able to read a newspaper.”

Googling around the internet I found a lot of sites where people had written in saying, “I am studying language XYZ, and I want to know how many words I have to know to be able to read a newspaper.”

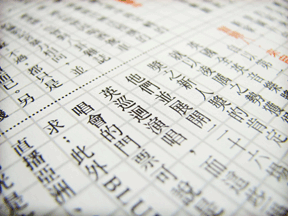

This question is particularly relevant for people who are studying Chinese, where each word is a character, and most students know the exact number of characters that they can read. Whereas students who have been studying Spanish, German, or Vietnamese for a period of years, wouldn’t generally know the exact number, or may not even know an approximate number of words that they understand.

This information is relevant for anyone studying a foreign language, including English, particularly if your goal is to study at a university overseas or to work in a professional job in the foreign language environment.

Checking a number of websites, the answers varied substantially.

On aksville.com, someone took the time to write a long reply, explaining that major newspapers, such as USA Today, are written at a 6th to 8th grade level and require approximately 3,000 words to read.

Another site, called blogonebytes.com: “I read somewhere that to be able to carry on a good conversation in “Mandarin Chinese” one should know about 3,000 characters, and about 7,000 characters to read technical books.”

A follow up comment by a reader on the same site said, “You will need to know a minimum of 3000 characters to be proficient. You will need to be able to speak and understand in the range of 5000-7000 characters.”

According to Omniglot, a site which I tend to have a lot of respect for, “The largest Chinese dictionaries include about 56,000 characters, but most of them are archaic, obscure or rare variant forms. Knowledge of about 3,000 characters enables you to read about 99% of the characters used in Chinese newspapers and magazines. To read Chinese literature, technical writings or Classical Chinese though, you need to be familiar with at least 6,000 characters.”

I had always heard that the range was somewhere between 1,500 and 3,000 words to read a newspaper. In the case of Chinese, I know that I can read right about 3,000 characters, and yet, I absolutely cannot read a newspaper. If you hand me a newspaper, I can pick out words that I know, but I can’t actually read and understand the stories.

In Bangkok, I have several friends who are extremely conversant in Thai, and they can read a menu. But they would need an entire day and a dictionary to read a single newspaper story. And even then, they wouldn’t understand everything.

With German, after four years of studying and working as a translator and researcher in the country, I can obviously read anything. But, I have no idea how many words I know. Now that I am embarking on my study of Bahasa Malay, and also making plans to go back and finish learning Vietnamese, I am becoming very curious how long it will take to get my reading level anywhere close to what it is in English or Spanish. My own experience with Chinese made me question this 3,000 word figure. Also, as a person who earns most of his living from writing for magazines, newspapers, and books, I would hate to believe that I only write a 3,000 word vocabulary , and on a 6th to 8th grade level.

As many times as I attended 9th grade, you would think I would be writing at least at high school level.

The two facts that I wanted to verify were, the average reading level of The New York Times, my hometown paper, and the average number of words per edition.

The first question was easy to answer.

The May 2, 2005 edition of “Plain Language At Work Newsletter”, Published by Impact Information Plain-Language Services, explained that there are two generally accepted scales for determining the reading level of various publications. They are the Rudolph Flesch Magazine Chart (1949) and the Robert Gunning Magazine Chart (1952). Both charts analyzed such aspects of a magazine or newspaper such as, average sentence length in words and number of syllables per 100 words. Based on this information, they assigned a school grade reading-level to the publication. According to this rating system, The Times of India was considered the most difficult newspaper in the world, with a reading level of 15th grade. The London Times scored a 12th grade reading level, as did the LA Times and the Boston Globe. The survey must have been flawed, however, because they assigned The New York Times a reading level of 10th grade, which is lower than the LA Times, when everyone knows quite well that New York is better than California or any other place which is not New York.

If you get most of your news from Time Magazine, you might be pleased to know that Time and TV Guide both scored a 9th grade reading level.

The survey didn’t cover newspapers written in languages other than English, but if we assume that we are shooting for an average 10th grade level, this will probably be close to what you need to read a newspaper in any language.

The next question was much harder to answer. How many words do I need to read the New York Times? I have never believed the low estimates of 3,000 or less, simply because every event that happens anywhere in the world, any human situation can appear in the Times as a news story and could of course, require the appropriate vocabulary.

To answer the question, I went to the June 4, 2010 New York Times online and I chose 8 articles, taken from several different sections, because I assumed they would all require different vocabulary. The stories were: “Pelicans, Back From Brink of Extinction, Face Oil Threat”, “BP Funneling Some of Leak to the Surface”, “John Wooden, Who Built Incomparable Dynasty at U.C.L.A., Dies at 99”, “An Appraisal : Wooden as a Teacher: The First Lesson Was Shoelaces”, “Should you be able to discharge student loans into bankruptcy?”, “On the Road to Rock, Fueled by Excess” as well as other tidbits, announcements and follow up articles.

In some cases, if the articles were very long, I didn’t take them in their entirety, assuming there would be much repetition of words.

In all, I took parts of about 8 stories, comprising 51 pages of text. The stories I took didn’t even represent 10% of the total content of this particular edition of The New York Time, June 4, 2010 online edition.

I pasted the words into a word document, converted them to a single column table, which ran over 450 pages long. Then I sorted the table alphabetically. Up to this point, it was easy, just pressing buttons. Next, I had to go through all 450 pages, all 10s of thousands of words, removing duplicates. It was one of the most tedious exercises I have ever conducted in my life. It was exactly the type of obsessive compulsive behavior that gets people locked up in mental institutions. It took 16 hours. By the 10th hour, I began hallucinating. Nearing the 12th hour, I believed I was a hummingbird of some kind.

I allowed plural forms of nouns, so I counted “car” once and “cars” once. I also included all forms of a verb, so “walk” once, “walked” once, and “walking” once. I counted proper nouns, including place names, as the names of people and countries will come up in the news and you need to know them. Also, in foreign language, particularly Asian languages, the grammatical forms and proper names may not even be recognizable if you haven’t studied and learned them.

When I was finished, I found that the random sampling of stories I chose contained 4,139 unique words. This was much higher than the estimates I had read on some websites, but was well in line with what I suspected. If I had the energy to complete a similar analysis of the entire edition, I would have to believe the number would increase. And if we monitored the newspaper over a period of one month, analyzing the text every day, and comparing the vocabulary against an accumulated list, I would imagine that it would grow. Most likely the difference in vocabulary from day to day would be small, but still, the necessary vocabulary would increase.

Comparing the dialogues in my Chinese textbooks with the vocabulary that appeared in these New York Times articles, much of what I learned in school was useless. For example, all foreign language textbooks have chapters devoted to shopping at the market, where you have to memorize tedious lists of Fruits and vegetables. In these Times articles, not a single fruit name was mentioned. Neither my Vietnamese, Chinese, or Bahasa textbooks include the names of heads of state of various countries. But obviously, these names came up in world news stories.

Below is a small sampling of words that I found in the news story which, I don’t know how to say in Chinese. Some of these words, I question, however, if the average 9th grader would know them. Do 9th graders know: abetted, absinthe, archeo-feminist, or bearish?

abetted albeit assesses bankruptcy biofuels able-bodied. Amandine assessment batch biography abortions ambivalent assets bawdy-sweet black-clad absinthe anachronistic asthmatic bearish bleak absurd. anarchic audience-pleasing Bedford blemish accord Appended aura befriended blockade across-the-board Archbishop autobiography behind-the-back blowout activists archeo-feminist autograph-seekers benefits bond Advocates articulate awfully best-selling booster aerodynamic assertion babbles bioenergy breakthrough

Names and proper nouns are important for understanding news stories. In language textbooks you may learn the names of major countries and the capital cities, but news happens in small cities and even villages as well. To read the news you need to know the names of political parties, famous people, economic theories, financial indices, global corporations, educational institutions, associations, and international organizations such as the UN.

All of these names were taken from the same collection of stories. Do you know how to say these in Vietnamese or write them in Thai?

Cypriot Delta Geneva Mediterranean Bihar Baltic Democrat Greece Nehru Turkish-controlled Brooklyn Denmark Uttar Metropolitan Nasdaq Iranian Dow Midwesterner Mayor Polytechnique Louisiana Durbin Scotch Reich Iskenderun. pro-Greek Dutch-Irish Rev. Latino Kentucky. California Baptist BENJAMIN Bonaventure/Agence Burke/Associated Cambridge Chicago-based Berkeley Pennsylvania. Bush Cyprus Barataria-Terrebonne Navy BP Dallas-Fort Audubon Gandhi. Bess Dalit Arce

How many of the above terms were you able to translate or transliterate into the language that you study? This is the level of reading that an adult native-speaker can do, and this should be your goal. If the task doesn’t seem daunting enough, remember, in this article, we were only concerned with vocabulary. But you could have a vocabulary of a million words not be able to understand a newspaper or a book. For real communication, you need a comprehensive approach to language, which includes culture, syntax, context, and grammar.

It’s a long stretch. I know. And it can seem impossible. But remember, every Sunday in New York City Catholic mass is said in 29 languages. For more than a century, large numbers of immigrants, my family included, have been coming to America and Canada in search of a better life. Most of them learned English with less than half of the education of the average person reading this article.

So, if your Grandma and Grandpa could learn a new language to a level of functionality, so can you.

Like Antonio’s writing?

Check out some of his fantastic books on travel, martial arts, language learning and endangered cultures.

]]>Antonio Graceffo is an applied linguist, and martial arts and adventure author living in Asia (check out our interview with him here). His books, including ”The Monk from Brooklyn”, are available at Amazon.com .

.

Normally, ALG says you do 800 hours of listening, then you start speaking, and you do writing and reading last. The reality is, however, if you are not at the ALG school in Bangkok, it is nearly impossible to arrange these type of lessons for yourself. And, strict ALG takes two years to learn a category three language, such as Chinese, Thai or Korean. Most people working in a foreign country can’t invest two years in learning, particularly if they are on a one year or two year contract.

Normally, ALG says you do 800 hours of listening, then you start speaking, and you do writing and reading last. The reality is, however, if you are not at the ALG school in Bangkok, it is nearly impossible to arrange these type of lessons for yourself. And, strict ALG takes two years to learn a category three language, such as Chinese, Thai or Korean. Most people working in a foreign country can’t invest two years in learning, particularly if they are on a one year or two year contract.

So, I modify ALG when I am doing my own learning and writing.

Next, the founders of ALG were concentrated on how to teach Thai to foreigners. In taking ALG out of Thailand and applying it to other countries, my personal feeling is that the game changes a bit because, unlike Thai, Korean is not tonal and the pronunciation is simple consonant vowel, consonant vowel. And second, the Thai writing system is extremely complex and you really shouldn’t learn to read until you have a very functional knowledge of the language. But in the case of Korean, Hangul is one of the easiest and most perfect writing systems ever developed.

Most people can learn Hangul in about a week, after that, you can read literally anything in Korean. Normally, I tell people to read last, because when you read you have an internal monologue which will be imperfect if you haven’t done sufficient listening first.

What I suggest, to speed up the process, but to also learn the language well, is to buy a university level Korean textbook, and hire a private tutor. Korean teachers will generally want to spend the first several lessons on the alphabet. Don’t let them. Don’t worry about the alphabet for a few weeks. It is probably better to hire a young university student who you can intimidate into teaching you the way you want to learn, as opposed to hiring an experienced teacher who only knows one way and will argue and fight with you.

Have your tutor read the dialogues in your book again and again. At home, listen to the audio CDs for the book. Do not start by having the teacher teach you the symbols or the characters of Hangul. Just follow along with your finger while the teacher reads. Do this for two or three weeks. You will begin to make guesses about what the different characters should sound like. You will begin to recognize words. You will slowly gain a rhythm for the language.

After several weeks, then you could spend a single lesson on the alphabet, to ensure that you know what each letter sounds like and how to recognize them. After that, you can read on your own.

At night, follow the written words on the page while you listen to the CDs. You can start writing at this point. It will help reinforce what you are hearing and learning. But remember, listening is still the key to learning a language and to avoid fossilizing mistakes. Never write an assignment and allow the teacher to take it home and mark it. You go over every assignment, verbally with your teacher, a number of times before you go home and write it. The next day, you should go over your homework verbally, with your teacher. Again, the teacher reads and corrects. You just listen and write. Think about your homework as a talking point, something to help you focus and contextualize your listening.

Don’t speak yet.

What I did with the Korean language was to buy as many level-one textbooks as I could find. There are about three or maybe four series of Korean textbooks sold in Korea. So, I bought all of them. I chose one that I only did with my teacher. The others I did on my own. You can get level one textbooks for free, just ask other foreigners who gave up on learning Korean. They will often pass the books on to you. Just write in them and fill them with ink, writing and rewriting each exercise.

My teacher and I went on like this for about a month or six weeks. Everyday, she read for me. In the evenings I listened to the listening for that book and the listening for the other books which I read on my own.

Eventually, when I started speaking, I only read out my answers from my main textbook while my teacher and I marked my homework.

With Korean language, the listening/speaking is not difficult in the sense of getting the pronunciation right. Actually, Korean, like Mandarin, has only a couple of sounds that we don’t have in English. BUT the listening is difficult because of the complex Korean grammar and registers of speech. So, when you first start “speaking” it should really be just reading grammatically correct and appropriate answers from your book. I did this for hours with my teacher. Occasionally she would ask me something that wasn’t in the book, but I would refuse to answer. You don’t want to start “creating” speech until you are ready. Stick with canned speaking practice for several more weeks.

Finally, you can start speaking. Again, it would be best to wait till the end of 800 hours, but this is not a reality for most people living in the country. So, maybe you start speaking at the end of two months of lessons. My vocabulary was already 2,000 words when I began speaking. And even then, I kept my speaking limited to what was in the book and eventually variations of what was in the book. You should move your reading and listening away from the book and into the real world pretty early on. But your speaking needs to stay in the sterile book world or you will create mistakes that you will never, ever be able to shake.

With all of my languages, once my listening gets to an acceptable level, I encourage people in the real world to talk to me in Korean, but I answer in English. The longer you stay at that level and the more total listening you do, the better your Korean will be when you open up your mouth and start speaking.

If you jump right into speaking, as most teachers want you to do, you will most likely never approach fluency. You will make errors of grammar and appropriateness of speech. Depending upon how early you start speaking you may even make mistakes in pronunciation which is truly sad because Korean is so perfect and easy to pronounce.

The keys to language learning are: dedication, hard work, listening, and discipline to avoid giving in to the temptation to speak too early.

Like Antonio’s writing?

Check out some of his fantastic books on travel, martial arts, language learning and endangered cultures.

]]> In addition to endless English listening input, Hulu.com is now a source of reading input, too. How could a TV site be used for reading input? The answer is closed captioning. Though intended for the hearing impaired, English captions are a wonderful tool for non-native speakers of English.

In addition to endless English listening input, Hulu.com is now a source of reading input, too. How could a TV site be used for reading input? The answer is closed captioning. Though intended for the hearing impaired, English captions are a wonderful tool for non-native speakers of English.

Thanks to Hulu’s new caption search feature, it is easier than ever to use closed captioning for language learning. Here’s how:

- If your reading skills are stronger than your listening abilities, try reading through the closed captions before you watch an episode.

- If you are watching a video and unsure of what was said, you can repeat a given section again and again until it is clear.

- If you want to go back and review the vocabulary from a particular episode again later, you can simply search for terms used during the show, and then automatically jump to the clip using that language.

The only downside is that Hulu is not available outside of the United States, so English learners living in other countries won’t be able to use this amazing tool.

Maybe TV isn’t so bad after all?…

To learn more, check out the following video and visit Hulu’s Caption Search page.

]]> The iPod Touch, and it’s big brother the iPhone, are perhaps the best language learning tools to date. Their portability and massive storage allow you to carry around your immersion with you no matter where you are in the world or how busy you may get at work or home. In addition to the benefits of downloading podcasts onto your iPod (which can be listened to on any portable media player or computer by the way), the iPod Touch and iPhone allow you to choose from literally thousands of applications (called “Apps” in the new tech vernacular). Most of the apps are free, with paid versions usually costing only a dollar or two.

The iPod Touch, and it’s big brother the iPhone, are perhaps the best language learning tools to date. Their portability and massive storage allow you to carry around your immersion with you no matter where you are in the world or how busy you may get at work or home. In addition to the benefits of downloading podcasts onto your iPod (which can be listened to on any portable media player or computer by the way), the iPod Touch and iPhone allow you to choose from literally thousands of applications (called “Apps” in the new tech vernacular). Most of the apps are free, with paid versions usually costing only a dollar or two.

Here is 5 top list of apps well suited for language learning:

1. Google Mobile (Free)

In addition to all the other uber-useful and always free Google tools (Gmail, Calendar, Docs, Tasks, Reader, News, etc.), the Google Mobile app takes you right to the world’s best translation software: Google Translate.

Features:

- Clean, easy to use interface

- Translate a single word, phrases or entire webpages

- Search by text or voice

- Google’s propriety translation algorithm produces surprisingly accurate translations

Download Google Mobile from the iTunes Store

___________________________________________

2. Wikipanion (Free & Pro Versions)

Wikipedia articles are a great source of reading input that fits your exact personal interests (in language learning, interest trumps all!) The problem is that viewing the normal Wikipedia site is bit tedious on smaller devices. To make things a little easier, Wikipanion repackages the content of Wikipedia into a streamlined mobile interface.

Features:

- Easy to view related articles

- Offline browsing (Plus)

- Add articles to the que for later reading

Download Wikipanion from the iTunes Store

___________________________________________

3. eReader (Free)

Don’t want to shell out another few hundred bucks for a Kindle? No problem! Just download eReader and view thousands of free and for sale ebooks.

Features:

- Choose from a variety of color combinations to make reading easy on your eyes (e.g. dark on light in bright rooms and light on dark in darker rooms)

- Annotate the text: add notes, bookmarks, highlights, etc.

- Read with one hand using the autoscroll feature

Download eReader from the iTunes Store

___________________________________________

4. Apple Voice Memos (part of iPod OS 3.1)

Language learners have long known about the benefits of recording conversations to later check their pronunciation and review difficult to understand sections of a conversation. The problem is that people get nervous when they know you are recording them. Using Apple’s high quality headphone mic and Apple Voice Memos, you can discreetly record yourself or others without anyone knowing.

Features:

- Ultra cool user interface with retro mic and voltage meter

- Easily email voice recordings

- Trim, rename and classify recordings

Read more about OS 3.1 on the Apple website

___________________________________________

5. Skype (Free)

The amazing VOIP (voice over IP) power of Skype is now available on iPod Touches and iPhones. Don’t rack up your cell phone minutes; use Skype’s instead. It’s free to call people when they’re online and very cheap to call normal phone numbers. You can even text now.

Features:

- Free calls and instant messages to Skype users

- Cheap calls and texting to everyone else

- Syncs your Skype contacts

Download Skype from the iTunes Store

___________________________________________

]]>Antonio Graceffo is a martial arts and adventure author living in Asia (check out our interview with him here).

His books, including The Monk from Brooklyn, are available at Amazon.com

“The rabbit and the lion walked through the jungle. All of the animals ran away. Afterward, the rabbit said to the lion, ‘I told you they were all afraid of me.’”

“The rabbit and the lion walked through the jungle. All of the animals ran away. Afterward, the rabbit said to the lion, ‘I told you they were all afraid of me.’”

This was the story I struggled through last week. Yes, I was sort of proud that it was written in Chinese, but it is quite humbling that most of my reading material is purchased in the books section of Toys R Us. Some of them came with free candy. Others were pop-up books. I particularly like those. All of them are decorated with little cartoon drawing of smiling monkeys and happy flowers.

If your ego gets away from you, as mine often does, just ask the nearest seven year old to help you with your reading practice. This will bring you back to Earth in a hurry.

Learning to read and write Chinese turns you into a study hermit. Chinese children spend five hours a day, from about age five to age fifteen or sixteen, writing endless lists of Chinese characters. In other words, it takes them ten solid years of studying five hours a day, seven days a week, to learn their native tongue.

One reason it takes them so long is because every single piece of vocabulary has to be taught. When you learned to read and write in school, your teachers taught you some very basic vocabulary. Probably through about sixth grade you had spelling tests and vocabulary exercises, but you were only taught a very small percentage of your vocabulary, the rest you acquired passively from listening and from reading and studying your other subjects. But for Chinese, every single piece of vocabulary has to be taught. Even native speakers can’t do much with a word they can say, but don’t know how to read or write.

As an adult foreign-learner you are at a huge disadvantage compared to the native speaker children. For one thing, they already know the meaning of every word.

When you first sign up for Chinese classes, in Taiwan or China, you are given a choice of speaking and listening only, or the complete set of reading, writing, speaking and listening. When I first began learning Chinese at Taipei Language Institute, for the purposes of survival, I chose speaking and listening only. At that time I was the only foreigner on two Chinese Kung Fu teams, training with each team once per day. This gave me several hours of exposure to the language each day outside of the 2-4 hours per day I spent in the classroom. As a dedicated learner, with the opportunity to hear and practice the language, I reached a point where I was getting through a chapter of our book every two and a half days.

One of my American friends, call him Jim, chose the complete set of read, writing, speaking, and listening. In the six months that it took me to complete all of the books from beginner to upper intermediate, he hadn’t completed book one. He could read and write every single word that he knew, but he knew only about 1,000 words when he left Taiwan.

We had another classmate, call her Su Ling, who was a Taiwanese American. At home, her parents only spoke Taiwanese. So, she had returned to Taiwan to study Mandarin for the first time in her life. She could neither read, write, speak, nor understand any Mandarin.

The three of us went to a restaurant, and the waitress automatically handed a menu to Su Ling, and began speaking to her in Mandarin. I interrupted, explaining to the waitress that, in spite of her looks, Su Ling didn’t speak Mandarin. The waitress smiled politely, and resumed her incomprehensible babble with Su Ling.

“Tell her again.” Said Su Ling, “I don’t think she believes you.”

When I finally was able to convince the waitress that I was the one she needed to talk to, she handed me the menu, which I immediately handed to Jim, the only one of us who could read. Jim read the menu aloud, which I understood, but we had to translate into English for Su Ling. When we decided on our order, I told the waitress what we all wanted.

Basically, the point of the story is, if you can’t read Chinese, it takes three people to order off a menu. And, since I often find myself dining alone, I needed to learn to read.

I returned to Taiwan in June 2008, and began taking private lessons in reading and writing in late July. Once I got through my first hundred characters, I realized that learning reading and writing would be a very, very different experience than learning speaking.

When I was learning to speak, I spent as many hours in front of my teachers as possible. The only way I could get any input, any new learning, was sitting with my teachers. But in reading and writing, you have to do it all yourself. The best student will be the one who puts in the most hours of homework. Before, I had the teachers teach me the new material, and I saw them twenty or more hours per week. Now, with reading and writing, I have to teach myself the new material. I work through the chapters completely on my own, and then meet with my teachers just to correct, or go over what I have already done on my own. My ratio now is only six to eight hours per week of lessons and twenty or more hours per week of self-study.

When we were at Taipei Language Institute, I remembered Jim telling me, “With the Chinese, for every single word you learn, you have to learn three things: the way it looks, the way it sounds, and its meaning.”

It’s true. With Chinese, unlike any European language, it is possible to know thousands of words, and not be able to read them or write them. This is where I was when I started studying. The other possibility is that you see a word. You know how to pronounce it, but you forgot what it means. Or, that you remember the meaning, but forgot how to say the word.

One example is that the Chinese have about three ways to express the concept of “a week.” Each of these is composed of two characters. Very often I am reading, and I know the sentence says, “I study Chinese three times per week.” I use the word “xin qi” to express one week, but my teacher corrects me. “These are the characters for ‘li bai’ which also means week.” Two different sets of characters can have the same meaning, but different pronunciations. In English we have a lot of synonyms, which are written and spelled completely differently, but have similar meanings. But, because of our phonetic writing system, it would be impossible to look at the word “demise,” and say “kick-off.”

For myself, the last two don’t happen as often because my vocabulary, going into my basic reading class, was already well over 2,000 words. So, while I could maintain a fairly normal conversation, my reading book has sentences like, “My name is.” and “How many glass of tea did Mr. Wang take?” When any of my Taiwanese friends open my textbooks they always look at me in surprise. “This is so easy. You are way beyond this.” They learned to read so long ago that they forgot that someone who speaks Chinese well may not know how to read at all.

Interesting, my second-grade students don’t think there is anything strange about what I am doing. They watch me do my homework and often say proudly, “Teacher, I can read all of that.” Half way through the page, though, they inevitably stop and ask me, “What is this word?” Yesterday, one of the kids asked me about five different Chinese characters in my homework. I was so proud of myself. If I study really hard, I might qualify for elementary school.

In learning to read, I thought a lot about what Jim said. And, although I understand the concept of why, at universities in the west, students are taught all four skills from day one, this must be a very daunting, very discouraging way to learn. Progress would be so slow. In my case, having learned so many words first, even with reading and writing I am getting through a chapter every three days. This is only possible because I already have the speaking and listening. Maybe this method of study would be better for university students in other countries. Maybe it is only possible if you are studying in a country where the language is widely spoken.

So much about L2 (second language) acquisition has been written based on how children acquire their L1 (first language). There are some fundamental differences, however, namely that an adult has more logic and experience to draw from. An adult also understands the mechanics and use of language. When I teach second graders that they have to use good grammar, they may not even be aware that Chinese has grammar. And certainly, their Chinese grammar wouldn’t be perfect yet.

One point that makes my current study of Chinese reading and writing more similar to the way Taiwanese children learn is that, like a Taiwanese child, my vocabulary is already large and I am already able to speak and communicate. Now, I have to learn the reading and writing. Even in the more advanced reading books, if I get stuck on a word, it is normally because I don’t know how to pronounce or recognize a particular character. But, if my teacher reads the character, I understand. This is exactly the case for Taiwanese children.

There are huge differences in vocabulary and usage, however, but more on this later.

One of my Tainan friends, call him Chuck, has lived in Taiwan for twenty years. He learned all four skills from day one. He had some very interesting points to make about language. First, he said, “I studied hard for the first five years. Then I took the exam and I scored 3,000.” Meaning his test results showed that he knew 3,000 or more characters. Three thousand is the magic number. At that level you should be able to read anything, even college textbooks, but you will still need a dictionary for specialized vocabulary that you may encounter. “I stopped studying at that point,” continued Chuck. “And my Chinese stopped improving. I recently retook the test and still scored 3,000, so I haven’t lost anything. But fifteen more years of living here didn’t cause me to improve.”

Chuck was touching on a subject I have written about extensively, namely, being in the country doesn’t mean you are immersed or that you are learning. Chuck has lots of Taiwanese friends and speaks Chinese all day, but in the course of a normal day or normal conversation, he doesn’t go beyond his three thousand words. The only way to move forward is to study.

Chuck also said, “There is nothing anyone can do for you when you learn to read or write. Even your teachers can’t really help you. If you get stuck or you make a mistake, they can correct you. But you have to learn it on your own.”

And this means countless, lonely hours of reading and writing. Reading and writing Chinese, you become a study hermit.

Chuck told me about a foreigner who was teaching in Taiwan in the 1980s when the country was a bit less developed and regulations were in some ways looser. This foreign adult wanted to learn Chinese, so he went to an elementary school principle and obtained permission to attend classes, along with the children.

“For four years he sat in the back of the classroom learning the stuff children learn,” said Chuck. “But to me, it seemed a little pointless. He didn’t need to know the name of every utensil in the house.”

Now we are back to the differences in vocabulary and approach of an adult learner, verses a child. I haven’t tried it, but I would bet money that if I took my basic reading dialogue entitled “At the Money Changers” and showed it to my second graders, they wouldn’t be able to read any of it. And if I read it aloud, the probably wouldn’t know words like currency exchange, travelers checks, or the technical names for currencies such as American Dollars or New Taiwan Dollars. They might not even be able to read the rates, which are posted in decimal form. At the same time, I don’t know how to say baby bottle or game consul. And I always forget what to call your father’s younger brother.

And perhaps most embarrassing, the second graders didn’t stutter when they were reading the story about the lion and the rabbit. It took me two days to read that.

This hits on my other writing focus. There is a myth that children learn language faster than adults. It’s just not true. For my work as an adventure writer, I need a lot of specialized vocabulary in the fields of international relations, politics, and geography. There is no way second graders would understand any of the concepts, so how would they learn and use that vocabulary. Often, we are talking about a second grader’s inability to learn these words and concepts in a foreign language. But now, I am comparing me, and adult learner, learning Chinese, to native speaker second graders. While they have many advantages in general reading and writing, by virtue of being native speakers, it will be years before they could read and explain the texts I will be using at university, a few months from now. And of course, if we compare an adult foreign leaner to a child foreign learner, the difference becomes even more extreme.

Learning to read Chinese means memorizing one or more characters for every single piece of vocabulary in your head. The characters are based on over a hundred base characters. So, after a while, you can see a new character and guess that it has something to do with talking or driving or is esoterically related to the heart or an open door, but for the most part, it is pure memorization.

The Chinese language is like an epic movie, starring a cast of thousands of characters.

Like Antonio’s writing?

Check out some of his fantastic books on travel, martial arts, language learning and endangered cultures.

]]>