This tome of language awesomeness contains over 500 pages of language learning advice, tips, and success stories, with contributions from 43 authors, including Moses McCormick, Steve Kaufmann, Benny Lewis, Stuart Jay Raj, and countless others language heroes.

The book is the brainchild of Claude Cartaginese of Syzygy on Languages, who also edited the work. In his own words, The Polyglot Project is:

“…a book written entirely by YouTube Polyglots and language learners. In it, they explain their foreign language learning methodologies. It is motivating, informative and (dare one say) almost encyclopedic in its scope. There is nothing else like it.”

]]>

But this is not necessarily a bad thing considering the myriad advantages of ebooks, especially for learners of foreign languages.

The Rise of eBooks

Here are a few reasons why the ebook is beating print books to a “pulp” (pun intended):

Lower Production & Distribution Costs

This allows for lower retail prices, putting books in the hands of more and more readers. And many ebooks are available at no cost at all, including literary classics no longer covered by copyright (e.g. Project Gutenberg) and new works that are free by choice (this is one of the common “freemium” strategies where an ebook is used for free marketing to promote other paid content or services.)

Read Anytime, Anywhere

You can literally carry thousands of ebooks with you on your mobile device or ebook reader. Language learning is then just a click away whether you are on the bus, a plane, or bored to tears in a meeting. And if you forgot to download books at home, you can always download more on the go via WiFi or even 3G networks.

More Time Efficient

Many ebook readers allow you to easily cut and paste words and even look up unknown terms using built in dictionaries. This can save the learner hours and hours, especially in ideographic languages that usually require looking up characters by strokes, radicals, or handwritten input.

So now that I’ve made the case for ebooks, let’s look at my two favorite weapons of choice for using ebooks in foreign language learning:

Best Ebook Readers

There are heaps of ebook reader devices on the market today (the Amazon Kindle, the iPad, the Sony PRS series, the Barnes & Noble Nook, etc.), as well as numerous ebook reader apps available for Android devices, iPhones, iPads, iPod touches, Blackberry devices, PCs and Macs. After trying out hundreds of different devices at last year’s CES and stealing…I mean “borrowing”…a few of my friend’s devices for further testing, here are my two finalists:

1st Place: The Amazon Kindle 3G

1st Place: The Amazon Kindle 3G

Available from Amazon.com (Kindle 3G: $189 USD, Kindle (WiFi version): $139 USD)

While I am a full-fledged Apple fanboy, I must give Amazon credit where credit is due. Despite serious competition from the Apple iPad, Sony’s various ebook readers, the Barnes & Noble Nook, and myriad other me-too products, the Kindle remains a hot seller, and my humble opinion, the world’s best ebook reader.

Here’s what I love most about the Kindle:

1) E ink is easy on the eyes and your battery.

Unlike the pixels used on computers and smartphones (which can wreak havoc on your eyes and zap your battery), the Kindle’s use of E Ink creates a reading experience pretty darn close to physical books, all while consuming very little battery life. They accomplish this amazing feat by employing millions of itsy-bitsy, electronically charged “microcapsules”, within which there are tons of little black pigment pieces and white (or rather, light gray) pigment pieces. Text is produced by causing the black pigments to run to the top of specific microcapsules, while the background is created when the gray pigment is forced to the top. The Kindle display is also much easier to read outside in the sun, while most other devices (including the iPad, iPhone, and iPod touch) suffer from serious glare problems.

2) Direct access to the world’s largest book store pretty much anywhere in the world.

Users can wirelessly access over 750,000 ebooks, plus heaps of audiobooks, newspapers, magazines and blogs, in over 100 countries worldwide. And unlike the iPad, the 3G wireless connectivity is provided free of charge.

3) Great Apple and Android apps.

![]()

If you don’t want to fork over the funds for a Kindle, or you already own one but don’t feel like lugging it around all the time, you can always just download the free Kindle app.

Available for Android, iPhone, iPad, iPod touch, Blackberry, Windows Phone 7, PC, and Mac.

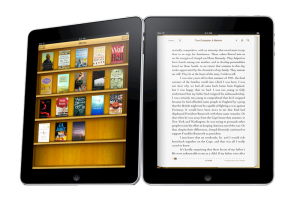

2nd Place: Apple iPad and iBooks

iBooks is free download in iTunes. The iPad 2 is available at the Apple Store, Verizon and AT&T.

1) More than JUST an ebook reader.

1) More than JUST an ebook reader.

My only gripe with the Kindle is that it is only an ebook reader. With the iPad, iPhone, or iPod touch, on the other hand, your device is only limited by the apps you download to it. I currently have about 100 hundred apps on my iPod touch, including Skype for calling tutors and language partners, Evernote for keeping notes of new words and phrases, iLingQ, ChinesePod, SpanishPod, and on, and on, and on…

2) Sexy, intuitive user interface.

The Kindle interface isn’t bad by any measure, but it pales in comparison to the rich, elegant design of Apple iBooks. The new “retina display”, available on the iPhone 4, iPod touches (4th gen), and likely the next vesion of the iPad, creates extremely crisp, vivid images, and makes reading text far easier than on lower resolution devices.

3) Excellent built in dictionary, bookmarks, highlighting and search features.

iBook’s built in dictionary, bookmarks and highlighting tools are a thing of beauty. To look up a term, you need simply tap the word and then click “Dictionary” from the pop-up menu. To highlight, you again just tap a word and then drag the handles to the left or right to select the words or sentences you want. Bookmarking requires just a quick tap in the upper right corner. Best of all, you can then quickly go back to your saved highlights or bookmarks using the table of contents tab. Also, you can use the search feature to quickly find all instances of a particular word (a very useful feature for language learners as it allows you to quickly see how a particular word is used in context.)

Getting the Most Out of Ebook Readers

As we’ve seen, ebooks and ebook readers are wonderful language learning tools indeed. But as ESLpod’s Dr. Jeff McQuillan puts it, “A fool with a tool is still a fool.” Here then, are some tips on how to best apply these amazing new tools.

1) Don’t fall into the trap of reading more than you listen.

Reading is an important part of language acquisition, and is an essential component of learning how to write well in a foreign language. But remember that listening and speaking should be the focus of language study, especially in the early stages of learning. It is all too easy to spend too more time with your nose in a book than listening to and communicating with native speakers, especially for introverts and those who have been studying for too long with traditional, grammar and translation based approaches.

2) Read an entire page before looking up unknown words.

Lest you get distracted and lost in the details, I suggest making at least one full pass through each page in your ebook before looking up unfamiliar words.

3) Choose books that are just a tad beyond your comprehension level.

By “comprehensible” I mean that you can understand about 70 to 85% of the text. Too far above or below this and you will quickly get bored and likely give up.

4) Use the Kindle’s Text-to-Speech Tool.

The Kindle and Kindle 3G can literally read English-language content out loud to you. Use this feature when you are doing other tasks that require your vision but not your ears, and as a way of building your listening comprehension. I suggest listening to a passage first and then reading to back up your comprehension.

5) Get audio book versions of ebooks you read.

While the Kindle’s text-to-speech tool works well, it can get a bit monotonous with its robotic pronunciation. For longer books, I suggest buying the audio book version the book, which tend to be read by professional voice actors, and are therefore far easier to listen to… Audio books are available from Audible, iTunes, and countless other site, and make sure to check out the free Audiobooks app for the iPhone, iPad and iPod touch.

]]>I have sat quietly on the sidelines for some time now, politely listening to both sides of the argument. But it’s time to blow my referee whistle because both teams are “offsides” (Okay John, enough sports analogies already!)

The Argument is Flawed to Begin With…

The problem with the whole argument is that input and output are not mutually exclusive components of language learning. You need both. The key is order and balance.

1. Listen first, then speak

When just starting out in a language, it is important to get as much listening input as possible. Just like when you learned your first language, you need to first go through a “silent period” where your brain gets used to the patterns and phonology of the language. Once you have filled your teapot up with enough listening input, language will naturally want to start pouring out. That’s when it’s time for a tea party to put into practice what you have assimilated (and no, I am not promoting that kind of “tea party” as I am a bleeding-heart liberal…)

But unlike little babies, adults can also rely on reading input to back up what we listen to. This difference (along with the fact we don’t have to wear diapers) gives adults a major leg up on babies learning their first language.

To this end, try to find short, simple dialogues of actual native speakers with transcripts. Then listen and read, listen and read, and listen and read again as many times as your schedule and sanity allow. My personal favorite transcript-equipped podcasts are produced by Praxis Language (ChinesePod

, SpanishPod

, FrenchPod

, ItalianPod

and EnglishPod

) and LingQ (English, French, Russian, Spanish, German, Portuguese, Italian, Korean, Chinese, Japanese, and Swedish). I can’t stand the overly stilted, monotonous dialogues found on most textbook companion CDs and suggest you avoid them like the plague.

2. Take equal doses of your input and output medicine.

Once you have gone through your silent period (which will be input-centric by definition), try to spend an equal amount of time on input activities (listening to podcasts, reading blogs, etc.) and output activities (speaking with friends or tutors, writing a blog post in the foreign language, etc.). It may be nerdy, but I literally use the stop-watch feature on my iPod touch to time my input and output activities each day…

If you follow the above regimen, your foreign language skills will progress quickly, efficiently, and most importantly, enjoyably. However, if you follow the advice of the extremists on either side of the input-output debate, you are in for heaps of problems and a world of pain. Here’s why:

Output Only Problems

Proponents of the “Output is awesome; input is lame” philosophy suggest that learners just “get out there and start communicating with native speakers”. This approach, while certainly sexier than what I prescribe above, has a number of problems:

1. Nasty mispronunciation habits.

Bad pronunciation habits develop when you pronounce things how you think they should be pronounced based on your overly limited listening exposure to the language, and your logical, but nonetheless incorrect, assumptions based on how words are spelled but not pronounced.

2. You’ll be that annoying guy at the bar.

Because you have a limited vocabulary and only understand little of what is said to you, you will likely attempt to control conversations by keeping them on topics you are familiar with, using phrases and vocabulary you have memorized. All but the most patient interlocutors will get bored or annoyed by such one-sided conversations. Don’t be that guy.

3. You probably won’t enjoy the process and give up early.

Many would-be language learners give up because they simply don’t enjoy the process. Much of the angst, tedium and phobias stem from having to speak before one is ready. Language teachers are the worst perpetrators, presenting you with new words or phrases one minute, and then expecting you to actually use them the next. Well-meaning friends or language partners are no better, trying to “teach” you new words and phrases and expecting that you can actually use them right away. Assimilation takes time and repetition, so don’t beat yourself up if it takes a few times (or a few hundred times) of hearing or reading a new word or phrase before you can actually use it.

Input Only Problems

If, however, you spend months and months diligently listening to your iPod and reading online newspapers, but never actually speaking with native speakers (by design or chance), you will understand quite a bit of what goes on around you but will struggle to actually verbalize your thoughts well or have natural exchanges with native speakers. This happens because:

1. Proper pronunciation is a physical feat.

You can’t think your way through pronunciation (believe me, most introverts have tried and failed!). Good pronunciation requires that your ears first get used to the new language (i.e. through getting lots and lots of listening input), and then also getting your lips, tongue and larynx used to new sounds not found in your native tongue, which of course takes lots and lots of talkin’ the talk.

2. Speaking and writing identifies your learning gaps.

Until you actually try to say or write something, you won’t know what you really know. While you may passively recognize certain words, phrases, idioms or Chinese characters, you may still struggle to say or write them. This is even true for your native language (as I found out when I first started teaching English and was confronted with such conundrums up at the white board as “Wait a second…How in the hell do you spell “misspelled”?)

The more you speak and write, the more you know where the “holes” are in your language cheese, and the easier it will be to fill them with focused study and review.

Conclusion

So as in all things, the extremists tend to be just that: extreme. They tend to get more attention, but the efficacy of their advice tends to be an inverse proportion to their popularity…

To become fluent in a language, just consume a balanced diet, rich in listening and speaking, with plenty of reading and writing sprinkled in for flavor.

]]>All in all, the site is very similar, in a good way, to LiveMocha (read my review of LiveMocha here). Both use a “freemium” model, offering both free and premium services, which is great for new users who want to get their language learning feet wet before committing to a monthly credit card charge. Both are social networks, relying upon and benefiting from crowd sourcing to correct user writing samples, provide conversation practice, etc. There are, however, many subtle differences between the two sites; some good, some bad…

The Good

1) Excellent User Interface.

I love Busuu’s Language Garden visual shown on your personalized landing page (you’ll see it once you have registered). It’s attractive, intuitive and a pleasant departure from other sites that just show a boring table or list.

Busuu also uses high-quality stock photography that does a good job of creating a clear visual context. Rosetta Stone and LiveMocha also use a similar approach, but I find that they often use unclear pictures, leaving the learner a little confused about what concept, idea, or vocabulary item they are trying to impart. From what I have seen, this doesn’t seem to be as much of a problem on Busuu.

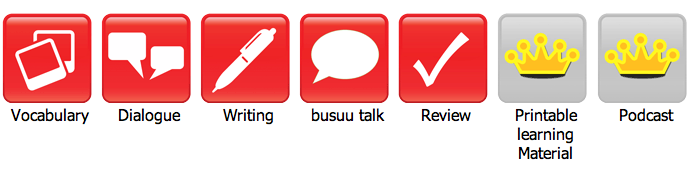

One of my favorite little features is the blinking icon effect showing which section of the lesson is next (the system will keep track of which sections you have already completed and then show you what to do next.)

2) Conversational beginner materials.

From the very first lesson, you will be hearing and reading natural (albeit simple) phrases like “How’s it going?”, “Where are you from?”, and “I’m sorry, I didn’t know she was your sister!” Okay, I made up the last one…

This is in contrast to LiveMocha, which starts off with a number of simple, declarative sentences to demonstrate certain simple adjectives, pronouns, etc. (e.g. He is tall. She is short. The man is fat. The girl is thin.) The idea of course is to get you used to how the language works and introduce basic vocabulary within a sentence. The problem is that most beginning language learners want to learn some useful phrases as well so they can actually say something once they arrive in the foreign country. You are fat probably won’t get you very far at a bar…

3) Great iPhone / iPod touch app.

The Busuu apps are extremely well designed, and as far as I can tell, include nearly all the content available on the website. As is often the case, I actually prefer using the app version over the website equivalent as it is more tactile and their are fewer visual distractions (less screen real-estate forces the designers to only include what is absolutely necessary.) And best of all, the apps are free!

The Bad

1) Annoying AdSense advertisements.

I completely understand the need to monetize the website, but random, third-party banners are not the answer. I, like many people in my generation, instinctively tune such ads out and will NEVER click them no matter how many times they flash in my face. I think Busuu would be better off placing more ads for their premium offerings as LiveMocha does.

2) Annoying comprehension questions.

Some comprehension questions ask information about specific people mentioned in the dialogue. I would much prefer exercises that reinforced the vocabulary and grammatical structures, not specific biographical information about characters. Better yet, they could present a number of dialogues using different characters and content information, but based around the same phrases and structures. Called “narrow listening”, this approach would help improve intake and retention, while also reducing the monotony involved in listening to the same piece of audio again and again.

3) A few too many bad apples…

On multiple occasions, users who agreed to “correct” my writing samples would simply copy what I wrote and paste it in the comments with no changes or comments whatsoever. I assume they did this in an effort to quickly earn “Busuu Berries”, points that can be exchanged for otherwise pay-only services on the site. Busuu needs to figure out a better way to patrol feedback. My suggestion is that they only assign points after the author of the writing sample has thumbed up the feedback.

My Verdict

If you are looking for a good free language learning solution online and are not learning a less common language (at the time of writing, Busuu only offers materials for a handful of major languages), then I definitely suggest checking out Busuu. Now if they only offered the Busuu language itself… It would be great to become the 9th speaker!

]]>The site has been well received by most, and comes strongly recommended by many language bloggers, school teachers, and individual learners.

Steven J. Sacco, a Language Professor at San Diego State University, has this to say about LiveMocha:

“Livemocha is the best online language program I have seen and used—vastly superior to Rosetta Stone in terms of cost and the variety of language functions it offers.”

So how does this blogger feel about LiveMocha? Here’s a quick look at the good and bad as I see it.

The Good

The best aspects of social networks

With so many registered users, LiveMocha provides a massive pool of potential tutors and language partners. The best part of this quid pro quo, reciprocity-based system are the corrections provided by native speakers. It’s win-win: they get some “Mocha Points” (exhangeable for otherwise pay-only features on the site) and you get free corrections. Not a bad deal. And you can of course correct the writing and speaking samples of people learning your native tongue. There will be frequent pop-ups asking you to do just that…

Numerous languages to choose from

LiveMocha currently offers courses in 35 languages making the site quite the polyglot wonderland. The following languages are offered, though not all of them are equally fleshed out: Arabic, Brazilian, Bulgarian, Catalan, Czech, Dutch, Esperanto, Estonian, Finnish, French, German, Greek, Hebrew, Hindi, Hungarian, Icelandic, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Mandarin, Persian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Spanish (Castellano), Swedish, Turkish, Ukrainian, Urdu. Phew, that’s a lot of “languaging”…

Lots of free content

It is always a good idea to test drive new materials before opening your wallet or purse. LiveMocha offers 3 units for free, with 5 or so lesson per unit, each including a variety of activities. Which leads to the next good point…

A wide range of listening, speaking, reading and writing activities

In each lesson, you will receive multiple exposures to target vocabulary and structures, with a good mix of listening and reading input. I especially like the “drag & drop” writing activity as it tests your understanding of basic structures and word order without requiring overt output before learners are ready for free writing exercises.

Language Specific Pop-up Keyboards

Although most browsers allow you to insert special characters, using LiveMocha’s pop-up keyboards (which are specific to whatever language you are studying at the time) saves you a lot of time over looking for the right accent mark, upsidedown exclamation point, or funky squiggle within the sea of shapes in browser symbol directories.

Correction by native speakers who are not necessarily trained teachers

Many people would consider this a disadvantage, but in my experience, untrained teachers are often better at identifying what doesn’t sound right and providing simple examples of more natural language. Teachers tend to miss the forest for the trees, and provide prescriptive advice on what one should say, not what real native speakers actually do say. Moreover, most teachers try to “teach” you the language, and as I reiterate time and time again, languages cannot be taught.

Informal language is presented first

Opinions differ on this issue, but I personally recommend (and much prefer) learning informal language before focusing on more formal equivalents. Why? Because in nearly all cultures, we rarely use formal language. When you start out in a language, it is inefficient to spend your precious time learning infrequent, specialized vocabulary and phrases. “Pardon me, but could I trouble you for dab of Gray Poupon?” can come later… Also, informal language tends to be shorter and therefore easier to learn, and often does a better job of demonstrating the basic structures of the language, where as formal structures are often archaic, semantically opaque constructions. Besides, travelers and new foreign residents will almost always be forgiven for being a tad bit too informal.

The Bad

The good news is that all of the following problems can be overcome or side-stepped based on how you use LiveMocha. And in my opinion, the pros of the site still far outweigh these cons…

Requires speaking and writing output too soon

When to begin producing output is a highly contested issue, and as of late, there have been some heated arguments on the topic between well-known language bloggers (many of you probably know to whom I refer). In my own experience as a language learner and teacher, I stand firmly in the “later but not too late” camp when it comes to output. Speaking and writing too soon is the single greatest cause of “fossilization” (see The Linguistionary for more on fossilized errors) and often leads learners to develop a fear of speaking the foreign language.

Too much overt focus on grammar

Grammar study is an equally controversial topic among language teachers, linguists, and polyglots (see this debate between LingQ’s Steve Kaufmann and Vincent of “Street-Smart Language Learning” for more on the topic). In my experience, a little grammar review from time to time can be useful, but should only take up a small percentage of your time with the language. Lots of input (and eventually, lots of output) is the key to true fluency, not memorizing complex information about the language that you have virtually no chance of utilizing in real time.

Reliance on (and a prevalence of) translation

Most language learners rely on—and expect their language products to provide—translations of everything they hear or read. While translation does make the learner feel more comfortable (and a little bit here and there can be helpful), knowing the equivalent of each word or phrase in your native language is certainly not necessary to learn a language. Remember: you learned your native language without translating to or from any language. The key is to create such highly contextualized situations that you don’t need to translate. LiveMocha does a fairly good job of this with their use of annotated pictures, but they could do more to contextualize lessons (especially those for absolute beginners) by adding sound effects and video clips.

Some bad apples

With such a large community, you are bound to run into a few bad apples who abuse the system. The most common problem I encountered were users who just copied what I had written without adding any suggestions or corrections in an effort, I assume, to quickly earn “Mocha Points”. But as LiveMocha’s VP of Marketing and Product, Clint Schmidt, mentions during our interview (see below), the community will quickly vote down such users and they will be removed from the system if appropriate.

So there you have it. Overall, I think LiveMocha is an excellent language learning site and recommend it as a supplementary material to your other learning tools.

]]>