This word should be your mantra when learning a language. When you find yourself procrastinating, making excuses, and putting off speaking practice out of fear, this string of six letters can help put you back on track:

- I have enough time if I prioritize my day and put language learning first.

- I have enough materials. My problem is probably not a lack of resources but a lack of motivation.

- I know enough words to at least start a basic conversation, even if I stall a few seconds later. That’s what dictionaries and phrase books are for!

So enough excuses already! Time to stop complaining and start learning.

]]>This is especially true for learning new vocabulary. Instead of spending time on words and phrases you might need someday (or even Sunday), focus all your energy and time on just the terms you will need to use today. For example, if you will be going to buy a prepaid SIM card in Taiwan, you would want to commit the words “cell phone” (手機, shǒujī), “prepaid” (預付, yùfù), “SIM card” (SIM卡, sim kǎ), etc. to memory. The Chinese names of different bird species might be useful for your birdwatching trip next week, but such information won’t do you much good at the Taiwan Mobile (台灣大哥大) store and is therefore not JIT. It can wait.

As Tim Ferriss puts it in The 4-Hour Workweek:

]]>“I used to have the habit of reading a book or site to prepare for an event weeks or months in the future, and I would then need to reread the same material when the deadline for action was closer. This is stupid and redundant. Follow your to-do short list and fill in the information gaps as you go. Focus on what digerati Kathy Sierra calls ‘just-in-time’ in- formation instead of ‘just-in-case’ information.”

I previously wrote about the similarities between learning to ride a bike and learning a language, but in this post, I’d like to share the parallels between language learning and another major passion of mine: martial arts. Just like learning a martial art, mastering a foreign tongue requires time and effort (which is the real meaning of the term “kung fu”), the proper blend of “self-study” and “sparring”, a great deal of patience, and a focus on mastering the basics instead of always chasing flashy new moves or words.

I previously wrote about the similarities between learning to ride a bike and learning a language, but in this post, I’d like to share the parallels between language learning and another major passion of mine: martial arts. Just like learning a martial art, mastering a foreign tongue requires time and effort (which is the real meaning of the term “kung fu”), the proper blend of “self-study” and “sparring”, a great deal of patience, and a focus on mastering the basics instead of always chasing flashy new moves or words.

Both Require “Kung Fu”

One of my constant struggles as a language blogger is to find the right balance point between highlighting the importance of having fun in language learning and setting proper expectations about how much time and effort is required to reach fluency (however it is you define the term).

In both language learning and martial arts, you should do everything you can to ensure that you genuinely enjoy the learning process. Choose a good teacher, find other people to learn with, and find activities you love. But you must also accept that:

- Some requisite tasks will hurt (e.g. doing horse stances and learning conjugations).

- Some days you just won’t feel like learning and will have to force yourself to do so anyway.

This is where “kung fu” (功夫, gōngfu) comes in. The word actually refers not just to martial arts, but to any form of learning that requires a great deal of time and effort to master:

“Gongfu is an ancient Chinese term describing work/devotion/effort that has been successfully applied over a substantial period of time, resulting in a degree of mastery in a specific field. Although the term is synonymous in the West with martial arts (though it is most over rendered Kung Fu), it is equally applicable to calligraphy, painting, music, or other areas of endeavor.” —Andy James

I don’t know about you, but I think learning a foreign fits this definition perfectly!

Both Require a Blend of “Self-Study” & “Sparring”

Another challenge in both martial arts and language learning is finding the right balance between preparation and application.

Some learners spend all their time training or studying alone, putting off the messy process of sparring or speaking with others until they feel “ready” (a feeling that will never come). You get better at what you practice, so if your goal is to learn how to defend yourself from an attacker or participate in flowing conversations with native speakers, then you have to actually apply movements with someone trying to attack you and speak with actual human beings, not just your iPhone.

Conversely, some learners want to just jump in and start sparring or speaking on day one. This is certainly preferable of the two options (especially for languages since there is no risk of physical injury), but the importance of self-study and preparation must not be underestimated in either endeavor:

- The more hours you spend in a horse stance or doing Anki reps, the stronger your kicks and vocabulary will become.

- The more times you practice techniques and phrases with slow, perfect form, the easier it will be to apply them at full speed while sparring or speaking.

Start “sparring” as soon as possible, but don’t expect to have effortless, free-flowing exchanges with native speakers until you have spent the requisite time in your “linguistic horse stance”!

Both Require Patience

I freaking love movies, especially those that follow what Joseph Campbell called “the hero’s journey” or “monomyth” in The Hero with a Thousand Faces:

“A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

But there is big unintended problem with such hero flicks: by showing the transformation from beginner to bad-ass in the course of 2 hours or so, they make us believe (at least at a subconscious level) that significant change can happen almost instantaneously. In fact, the majority of the learning in such movies is crammed into a short “montage” scene, where someone goes from zero to hero in the course of an 80s rock ballad! This hilarious clip from South Park sums up this absurdity nicely. At a conscious level, all of us know that developing actual abilities will obviously take more than a few minutes. But these films can leave us with a short-lived sugar high, a hunger for instant gratification that will quickly evaporate once one realizes what actual training or study feel like. Use films to pump you up, but make sure to start out in a new language or martial art with realistic expectations about how much time it will take you to reach your personal proficiency goals.

Both Require a Focus on the Basics

In a similar vein, many new learners of martial arts or languages want to skip the basics and jump ahead to the “flashy” stuff, may it be jump spinning hook kicks or technical terminology. While there is a time and place for both, it is imperative to master the basics first. Just as you can communicate a great deal with a very small number of words (Dr. Seuss wrote Green Eggs and Ham using only 50!), a martial artist can defend themselves from an almost limitless number of attacks using a very small set of core techniques. The key is quality, not quantity. As Bruce Lee said:

]]>“I fear not the man who has practiced 10,000 kicks once, but I fear the man who has practiced one kick 10,000 times.”

I’ve been blogging about language learning for 6 years, teaching languages for over 10, and learning languages myself for 15. During this time, I have heard lots of excuses (and made a fair number myself I must admit) about why one/I cannot learn a language well. The most common three by far have been:

I’ve been blogging about language learning for 6 years, teaching languages for over 10, and learning languages myself for 15. During this time, I have heard lots of excuses (and made a fair number myself I must admit) about why one/I cannot learn a language well. The most common three by far have been:

- I don’t have enough time.

- I don’t have enough money.

- I’m not good at languages.

Now I don’t want to imply that these are completely invalid reasons why one fails to learn a language. Sure, having more free time would certainly make it easier to fit in the requisite hours needed to reach conversational fluency. Bags of cash would make it much easier to visit countries where the language is spoken, pay for tutors or classes, and buy the best resources available. And being a savant like Daniel Tammet would make the language learning process go much faster than us mere mortals (he learned enough Icelandic in 7 days to handle a media interview in the language!).

But it is imperative that would-be language learners understand that:

- Anyone can make at least a little bit of time each day to spend on language learning.

- Everything you need to learn a language can be found online or at your local public library for FREE.

- Everybody can learn a foreign language, even if it takes some of us longer than others.

The gap between making the above excuses and making serious progress in a language is not time, money, or ability but motivation. If you really want to learn—nay, must learn—a language, you will find the time by cutting out less important things, you will figure out how to acquire the necessary resources, and you will eventually get used to a language’s pronunciation, grammar, vocabulary, etc.

The hurdles are inside your head, not on the clock, in your wallet, or within your genes. Now stop making excuses and start making progress.

]]>In the traditional brute-force method of memorizing vocabulary (the default approach worldwide), the learner writes a particular word or character dozens and dozens of times, hoping that it will somehow stay in their brain long enough for the next test or conversation. But unless you have a photographic memory, you will probably find that the information you worked so hard cram into your noodle is nowhere to be found just a few hours later. It’s demoralizing. You think to yourself, “See? I told you I’m not good at languages! I told you I have a crappy memory! Screw it; I’m just gonna watch House of Cards and eat an entire pint of Cherry Garcia.”

But before you give up, waste the entire weekend on Netflix, and develop insulin resistance, please realize that YOU are not the problem! Despite its ubiquitous use, rote memorization only works for an extremely small percentage of learners. Fortunately, there are three superior vocabulary acquisition approaches that work with (not against) how the adult human brain encodes and prioritizes information: 1) Mnemonics, 2) Spaced repetition, and 3) Context.

1) Create Crazy Mnemonics

Most of you have probably already dabbled in mnemonics in school, perhaps when trying to memorize the order of the planets. For example, the silly sentence “My Very Educated Mother Just Served Us Nine Pizzas” might help you remember the that the planets are ordered Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto. You would of course need to update this mnemonic now that Pluto has been demoted from planet status.

Even better would be a “linking system” that relies not on sentences but vivid stories. Tony Buzan shares the following example in his book Master Your Memory:

“Imagine that in front of you, where you are currently reading, is a glorious SUN. See it clearly, feel its heat, and admire its orange/red glow, Imagine, next to the Sun, a little (it’s a little Planet) thermometer, filled with that liquid metal that measures temperature: MERCURY.

Imagine that the Sun heats up, and eventually becomes so hot that it bursts the thermometer. You see all over the desk or floor, in front of you, tiny balls of that liquid metal Mercury, Next you imagine that, rushing in to see what happens, and standing by your side, comes the most beautiful little goddess. Colour her, clothe her (optional!), perfume her, design her as you will, What shall we call our little goddess? Yes, VENUS!

You focus so intently on Venus with all your senses, that she becomes almost a living physical reality in front of you, You see Venus play like a child with the scattered mercury, and finally manage to pick one of the mercury globules, She is so delighted that she throws it in a giant arc way up in the sky (which you see, as light glistens off it throughout its journey), until it hurtles down from on high and lads in your garden with a gigantic ‘thump’!, which you both hear and feel as a bodily vibration. And on what planet is your garden? EARTH.”

And on Buzan goes through all the planets, using vivid imagery, multiple (imagined) sensory inputs, a full color pallet, sexuality, stark contrast in size, etc. All of this seemingly extraneous information accomplishes one thing: helping your forever remember the order of the planets. It may seem like extra work up front, but in the long run, it is far more efficient and effective to learn information this way than through tedious rote memorization.

Rote memory fails because you are not giving your brain any hooks to attach the new information to. Crazy stories like above tie new, abstract information to memories already in our brains, things we can see (whether in our mind’s eye or on our own bodies like with knuckle mnemonics), or to concrete concepts that we can more easily recall.

So when trying to learn a new word, phrase, or Chinese character, create imaginative stories with multiple “hooks” that help to dig out the specific meanings, spellings, pronunciations, or strokes.

Here is an example on how to remember the kanji 朝 (“morning”) from Remembering the Kanji, a systematic mnemonic system designed by James Heisig to help independent learnings memorize the meaning and writing of all jouyou kanji:

“On the right we see the moon fading off into the first light of morning, and to the left, the mist that falls to give nature a shower to prepare it for the coming heat. If you can think of the moon tilting over to spill mist on your garden, you should have no trouble remembering which of all the elements in this story are to serve as primitives for constructing the character.”

If you are learning Japanese, download a free sample of Remembering the Kanji or get the book on Amazon. And don’t miss my interview with James Heisig.

2) Use Spaced Repetition

As the name implies, “spaced repetition” shows you flashcards at specific intervals based on how difficult or easy you previously rated them. The more difficult something is, the sooner (and more often) it will be repeated. Spaced repetition systems (or “SRS” for short) like Anki, Memrise, etc. are far more efficient than randomly reviewing a stack of unsorted flashcards since they (ideally) focus on just the information you need to practice at just the right time.

But a word of caution: although spaced repetition can increase efficiency, make sure that you don’t fall back on bad rote habits. Fill your flashcards with complete sentences and useful phrases taken from—and applicable in—real-life. Better still, add audio recordings of each sentence (ask your iTalki tutor or use Rhinospike to get free audio recordings by native speakers of your target language).

Read my post Spaced Repetition: What is It? Why & How Should You Use It? for more about SRS methods, apps, etc.

3) Learn & Use Vocabulary in Clear Contexts

The most potent way to improve the initial encoding and subsequent recall of new words is learning (and actually using!) vocabulary in context. By “context”, I mean out and about in the real world, doing real things, talking to real people, ordering real food, getting on real trains, flirting with real girls/guys, etc. Trying to memorize words at your desk is not only boring; it’s also far less effective. Studying alone in isolation creates far less robust memories because their is less urgency, less sensory input, less emotional feedback, and let’s face it, less of a point!

Read Anthony Metivier’s guest post Why It’s Impossible To Learn New Words And Phrases Out Of Context for more about the importance of context and how to create effective mnemonics.

]]>Given all the time and energy one spends trying to solve such puzzles, why not just learn a language instead?

I haven’t come across any studies yet that substantiate this (if you have, please send them to me!), but I hypothesize that learning languages has a far greater impact on brain plasticity than solving simple math or vocabulary puzzles. Think about it: solving a sudoku puzzle only requires sensory input from the eyes, basic addition, and movement of the hand to write the numbers. Speaking a language with another human being is a far more complex “bio-psycho-social” skill that requires:

- The use of multiple senses, including sight, sound, and physical movement (e.g. hand gestures and body language).

- The reading of subtle changes in tone, speed, volume, and body language.

- The discernment and production of exact auditory signals.

- The processing of complex syntax and production of grammatically correct sentences.

Perhaps more important than the potential neural benefits are the many practical advantages offered by foreign languages over puzzles and brain training apps. When you solve a crossword puzzle for example, all you are left with is temporary satisfaction and a worthless piece of paper. Learning to understand and speak a foreign language, on the other hand, enables you to:

- Delve more deeply into the culture, psychology, art, history, sports, cuisines, etc. of exotic lands. Yes, you can read about the history and philosophy of aikido (合気道・あいきどう) in English, but you will get much more learning “The Way of Unifying Life Energy” in Japanese.

- Travel more enjoyably. Your Lonely Planet guidebook might help you avoid some common scams or pick a hostel, but conversational fluency in the local language allows you to go further off the beaten path, avoid expat bubbles, find hidden gems, and interact with locals.

- Travel more cheaply. There are usually three prices for things: 1) the monolingual foreigner price ($$$), 2) the bilingual foreigner price ($$), and 3) the local price ($). While you may never be able to pass for a true local (whether from an ethnic or linguistic perspective), you can at least get close enough to reap significant cost-savings.

I may be wrong, but I don’t think sudoku, crosswords, or Luminosity will unlock any of these advantages… ; )

]]>Spaced Repetition Systems (or “SRS” for short) are flashcard programs designed to help you systematically learn new information—and retain old information—through intelligent review scheduling. Instead of wasting precious study time on information you already know, SRS apps like Anki allow you to focus most on new words, phrases, kanji, etc., or previously studied information that you have yet to commit to long-term memory.

Why Should You Use Spaced Repetition in Language Learning?

Because We Forget New Information REALLY Quickly Unless Reviewed

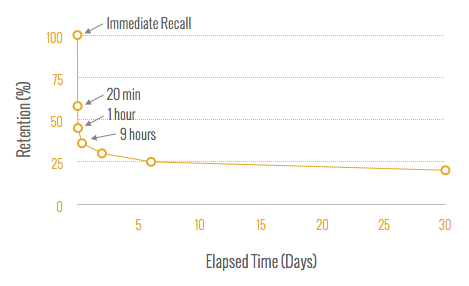

In 1885, a German psychologist named Hermann Ebbinghaus (1850-1909) put forth a paper titled “Über das Gedächtnis” (“On Memory”) in which he codified something every school student already knows: New information is forgotten at an exponential rate unless reviewed immediately. He plotted this rate along what he termed the “forgetting curve”.

As you can see, Ebbinghaus observed that he forgot new information almost immediately, with over half of the target information lost in just the first hour! Though his experiment was conducted only on himself (i.e. an N=1 study), his basic findings have been reproduced in more scientific studies since his time, and it’s generally agreed that we forget the vast majority of new information we encounter (as much as 80%) within 24 hours.

Because Spaced Repetition Lets Us Hack the Forgetting Curve

The good news is that we can use strategic repetition schedules to hack our memory and help control what sticks and for how long. Each subsequent re-exposure, if properly timed, can help push information we want to remember further and further into long-term memory.

This memory-boosting method was first popularized in language learning by Paul Pimsleur (1927-1976), the man behind The Pimsleur Approach. His particular brand of spaced repetition was dubbed “Graduated Interval Recall” (GIR), which he detailed in a 1967 paper titled “A Memory Schedule” (published in The Modern Language Journal). His proposed review schedule was as follows:

- 1st Review: 5 seconds

- 2nd Review: 25 seconds

- 3rd Review: 2 minutes

- 4th Review: 10 minutes

- 5th Review: 1 hour

- 6th Review: 5 hours

- 7th Review: 1 day

- 8th Review: 5 days

- 9th Review: 25 days

- 10th Review: 4 months

- 11th Review: 2 years

Modern SRS apps and software use even more complex scheduling, but lucky for us, all the math is done automatically by algorithms like SuperMemo’s SM2.

How Spaced Repetition Systems Work

Most SRS apps rely on self-ratings of difficulty to schedule reviews. For example, in Anki (one of the recommended apps I discuss more below), you will usually have 3 or so levels of difficulty to choose from:

- Red button: Used for “new” or “difficult” cards that you want to be shown again very soon.

- Green button: Fairly easy or somewhat familiar cards that you want to see again in a little while.

- Gray: Easy card that you don’t want to review for a while.

The exact interval of minutes, days, or months that each button represents will vary depending on how many times you have previously reviewed the card. For example, if this is your first time seeing a particular card:

- The red button will probably be labeled “1m” (i.e. 1 minute until the next review).

- The green button will probably read “10m” (i.e. 10 minutes until the next review).

- The gray button will probably read “4d” (i.e. 4 days until the next review).

How to Get the Most Out of SRS

Grade Yourself Honestly, But Quickly

A lot of learners get hung up on how to rate themselves, worrying they are giving themselves an overly generous score when they don’t really know the material or being too harsh on themselves when they were close but not perfect. Don’t fall into the trap of spending your valuable time deciding what you know instead of actually expanding what you know. When in doubt, just grade yourself in the middle and move on to the next card.

Use Complete Sentences & Clear Contexts

Avoid creating cards with just a single word or Kanji on the front and the reading or meaning on the back. These are boring and do little more than expand your declarative memory; procedural memory is what we are going for and that is only developed when seeing how words are used in context. Therefore, use complete sentences or even entire paragraphs.

Use Interesting Content

This may seem obvious, but I am constantly surprised by how many learners spend years forcing themselves through boring material. When you are assigned material by a teacher, you may not have a choice, but remember, this whole guide is about self-guided immersion: the choice is yours. Read and listen to content that excites you, topics that you would spend time with even in your native language. Then take chunks of this text or audio content you love (but perhaps don’t quite grasp entirely) and put them into your SRS deck.

Don’t be Afraid to Delete Cards

If you come across cards that are too easy, boring, or just annoying, delete them from your deck. Don’t think about it too much. If you find yourself wanting to delete a card but are unsure if you should, just delete it and move on. You won’t miss it. As Khatzumoto of All Japanese All the Time puts it:

“When your SRS deck starts to become more of a chore than a game, bad cards are most likely your problem.”

Recommended SRS Tools

There are loads and loads of apps available today that incorporate spaced repetition. Here are a few of the best:

Anki

Literally meaning “memorization” in Japanese, “Anki” (暗記) is one of the most popular SRS tools for language learning, and for good reason: 1) it has as heaps of useful user-generated decks, 2) it allows for extensive customization, and 3) it works on every major platform:

Anki Web (free) Anki Desktop (Mac, PC & Linux; free) AnkiDroid (Android, free) AnkiMobile (iOS, $24,99)

If you’re curious why three of the four platforms are free, while the iOS version costs 25 buckaroos, read Anki creator Damien Elmses’ justification:

“Taken alone, AnkiMobile is expensive for an app. However, AnkiMobile is not a standalone app, but part of an ecosystem, and the $17.50 Apple gives me on each sale goes towards the development of that whole ecosystem. For the price, you get not only the app, but a powerful desktop application, a free online synchronization service, and mobile clients for various platforms.”

Once you install your app of choice, make sure to download some of the shared decks created by other Anki users. There are heaps for most major languages, with lists for reviewing Chinese characters, practicing high-frequency words, etc.

Flashcards Deluxe

A good low-cost, high-quality, user-friendly alternative to Anki is Flashcards Deluxe from Orange or Apple. The app, available on both iOS and Android for $3.99, allows you to either create your own multisided flashcards (complete with audio and photos) or import pre-made decks from Quizlet.com and Cram.com.

Thanks go to Olly of IWillTeachYouaLanguage.com for recommending this app to me.

Flashcards Deluxe (iOS, $3.99) Flashcards Deluxe (Android, $3.99)

Skritter

Instead of the potentially problematic self-ratings used by most SRS systems, Skritter employs “active recall” (i.e. requiring us to actually write Chinese characters on the screen of our mobile device) to confirm which we know by heart and which we simply recognize but cannot yet produce from memory. Read my complete review of Skritter here.

Sign up for Skritter Japanese Skritter (iOS, free) Chinese Skritter (iOS, free) Android Public Beta

Memrise: Learning, Powered by Imagination

Memrise is arguably the best designed SRS tool on the block, but the site and apps offer much more than just a pretty user interface:

- Sound science. The entire Memrise experience is designed to optimize memory through the use of “elaborate encoding” (each flashcard includes community-generated mnemonics, etymologies, videos, photos, and example sentences), choreographed testing, and scheduled reminders (i.e. spaced repetition).

- Fun methodologies. Memrise points out that “we’re at our most receptive when we’re at play.” To that end, they have made efforts to incorporate gaming principles into their system. For example, they use a fun harvest analogy for learning (perhaps taking a page from the FarmVille playbook), breaking the learning process up into three phases: 1) Planting Seeds, 2) Harvesting your “saplings”, and 3) Watering Your Garden.

- Community. Perhaps the greatest benefit of Memrise is access to community generated “mems” (i.e. mnemonics), including a number of clever animated GIFs for Kanji.

Study Online (free) Memrise for iOS (free) Memrise for Android (free)

Massive-Context Cloze Deletions (MCDs)

Popularized by AJATT’s Khatzumoto, MCDs (“Massive-Context Cloze Deletions”) represent a simple—albeit extremely powerful—method for creating far more effective SRS cards. Instead trying to memorize (and test memory of) lots of information on your cards, MCDs focus on one single bit of target information at a time, may it be a Japanese particle, the meaning or pronunciation of a particular kanji, etc. In Khatz’s words:

MCD Plugin for Anki“Learning—which is to say, getting used to—a language used to be like climbing a mountain. With MCDs, it’s like taking a gentle flight of stairs. Everything becomes i+1, because we’re only ever handling one thing at a time.”

Surusu

Another product of “Great Leader Khatzumoto”, Surusu is a free online SRS tool that works hand in hand with the MCD approach. It works on all major web platforms (Explorer, Firefox, Safari, Mobile Safari), the only requirement being an active web connection (sorry, no offline studying folks).

Learn More About Surusu

Midori’s Bookmark Flashcards

Midori, my recommended Japanese dictionary app for iOS, gives you the option to study your saved words using spaced repetition:

- Click “Bookmarks” and choose one of your bookmark folders to study.

- Tap the share button (the upward arrow) and select “Flashcards”. Choose “Spaced Repetition” for the order.

- I recommend activating “Show Meanings” to test yourself on producing the Japanese word from an English prompt (it’s much easier but less valuable to test yourself on producing English meanings from Japanese prompts). You can always change this during a study session by tapping the share button and then “Options”.

- If you want to review the entire card and see example sentences as you review, pinch out on a flashcard. To return to the flashcards, tap the back button in the upper left.

Pleco’s Flashcard Module

The Pleco dictionary app for iOS and Android is by far the most powerful mobile Chinese dictionary available. The basic app and standard dictionary databases are free, but there are a number of paid add-ons to expand its functionality, including an excellent spaced repetition flashcard system for ($9.95).

Pleco for iOS (free) Pleco for Android (free) Browse Add-Ons

]]>

- Your confidence in your ability to learn.

- Your feelings about the language and culture.

- Your willingness to try things out.

- Your ability to learn from (and laugh at!) mistakes.

- Your tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity.

Here now are five of the most insidious psychological obstacles standing between you and fluency:

1) Negative Beliefs About Your Ability to Learn the Language

The most common—and arguably most destructive—psychological obstacle in language learning is the belief that you are not good at learning languages. Okay, maybe you didn’t do so well in high school or college Spanish class. But guess what? It’s probably not your fault. In most cases, poor performance in language classes is a reflection not of your inability to learn a language, but rather:

- How ineffective the standard academic approach to language learning tends to be for most people. A small percentage of learners with high linguistic intelligence manage to pick up languages in school, but most people do far better using more natural, immersion-based approaches that leverage multiple intelligences (visual-spatial intelligence, musical intelligence, bodily-kinesthetic intelligence, etc.). Some teachers do indeed try to integrate such methods, but the limitations imposed by large class sizes and standardized testing make the task all but impossible.

- How few chances you likely had to use the language in fun, meaningful, personally relevant contexts. Your language teacher may have planned some skits and “culture days”, but these are a far cry from the exciting, messy, real world interaction you need to reach conversational fluency.

- The fact you were required to learn a language, especially one you didn’t get to choose. Language learning should be optional. Or at the very least, students should get to choose which language they learn. And I don’t just mean a choice between Spanish and French. There are roughly 6,500 languages spoken in the world today; learners should be able to choose from a larger pool than just 2 or 3 Romance languages. If a particular language isn’t offered at one’s school, why not allow learners to develop a self-study program monitored by a faculty member or parent? The more power an individual has to choose, the more likely they are to take ownership of the learning process and put in the time and effort needed to make tangible progress.

2) Negative Beliefs About the Language & Culture

Looking back at my former English students, the one’s who made the most progress tended to be those who loved American culture, watched American movies, listened to American music, ate American food, and dreamt about traveling to—or living in—the United States. Those that had little interest in Americana (or the cultures of other English speaking countries) made far less progress no matter how important the English language may have been for their academic or professional careers.

In my case, my deep love and respect for Japanese culture gave me the extra fuel needed to continue putting one foot in front of the other even on days I really didn’t feel like studying.

3) The “Wait Until I’m Ready” Delusion

Many learners (especially those with perfectionistic tendencies) spend many years diligently preparing to use a language, flipping flashcard after flashcard, watching foreign films, listening to language podcasts, etc. All of this is well and good, but focusing only on input leads to an imbalanced language acquisition diet. You need to mix in healthy servings of output, too. Speaking and writing are by far the most efficient ways to solidify what you’ve previously learned, identify gaps in your vocabulary and grammar, and remind yourself why you started learning the language in the first place.

Look, I know it’s scary. There are so many things you want to say but don’t yet know how. So many unknown words and structures that fly right over your head. But so what? No matter how long you study, you will eventually have to go through this messy, two-way interaction. Why put off the inevitable? Why let fear stand between you and fluency? Regardless of your level, you can always try to communicate something today. If you only know five words, use those five words. If you don’t know any words yet, use gestures, drawings, inference, etc. to get your meaning across, paying close attention to what words and structures you hear as you go.

Imagine, for example, that you are at a market in Taiwan and want an apple. You don’t know the word yet, so you just point at one. There are many fruits on the table, so the merchant confirms which one by pointing at the pile of apples: “píng guǒ (蘋果)?” Boom, you now know the word for “apple” in Mandarin! He then asks you how many you want, but you don’t understand him. So he asks, “yī gè (一個)?” and holds out the universal gesture for the number one. You now know the number one in Mandarin, or more accurately, the phrase for “one thing”. Not bad for 10 seconds of person to person interaction! Had you tried to learn these words alone at your desk, you would miss out on the opportunity to:

- Eat the delicious apple!

- Mimic proper pronunciation.

- Encode words in a far more robust, multi-sensory way.

4) Fear of Making Mistakes & Looking Stupid in Front of Others

The “Wait Until You’re Ready” delusion above is largely fueled by fear. Fear of being misunderstood. Fear of not understanding others. Fear of making embarrassing mistakes. Fear of ordering the wrong food. Fear of getting on the wrong train. Fear of accidentally saying you’re pregnant in Spanish when you meant to say you are embarrassed! This fear is not completely unjustified. You will indeed make mistakes. Heaps of them. You will order the wrong food and get on the wrong train. You will accidentally insult someone when trying to express praise. But in the vast majority of cases, the only real victim is your pride. And the ego can only be bruised if you let your sense of worth be tied to your perceived ability in the language. Tie your pride instead to your willingness to try things out and laugh off mistakes, not how perfectly (or imperfectly) you can use a language.

As Viktor E. Frankl says in Man’s Search for Meaning:

“Between stimulus and response, there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.”

When you say the wrong word, butcher a sentence, misunderstand someone’s question, or make a cultural faux pas, you have a choice about how you respond to the potential embarrassment. Do you get frustrated or have a good chuckle? Do you let the gaffe serve as proof that you suck at the language or interpret it as an opportunity for growth? The choice is yours.

5) Frustration With Not Understanding Everything You Hear & Read

Just as most learners put off speaking and writing practice out of fear of making mistakes, many avoid powerful listening and reading opportunities because they grow frustrated with ambiguity and uncertainty. They stop watching an un-subitled foreign film half way through because they don’t know exactly what’s happening in the story. They limit their reading to bilingual books. They only talk with native speakers who also speak English, allowing them to always fall back on their native tongue when confusion arises.

While it is indeed ideal to choose materials just above one’s current level of understanding, and bilingual speakers do offer some advantages over their monolingual counterparts, don’t let a pursuit of the perfect resource or tutor stop you from getting valuable linguistic exposure right now with whatever and whomever happen to be around. The pursuit of perfection usually just leads to procrastination.

How about you? What psychological obstacles have you encountered in your language learning adventures? How did you overcome them? Let me know in the comments.

]]>

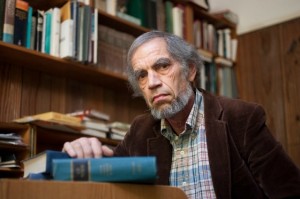

Stephen Krashen is one of my heroes. He is a linguist, researcher, education activist, and professor emeritus at the University of Southern California. I have wanted to meet him since I began studying linguistics in university, and finally had my chance at Ming Chuan University’s 2009 “Annual Conference on Applied Linguistics” in Taipei, Taiwan. He then agreed to conduct the following interview via email. Note that this interview was originally only available to newsletter subscribers, but since I am now offering Language Mastery Insiders a new bonus each month, I decided it was time for everyone to have the chance to enjoy Krashen’s unique brand of intellect and humor. Enjoy!

Stephen Krashen is one of my heroes. He is a linguist, researcher, education activist, and professor emeritus at the University of Southern California. I have wanted to meet him since I began studying linguistics in university, and finally had my chance at Ming Chuan University’s 2009 “Annual Conference on Applied Linguistics” in Taipei, Taiwan. He then agreed to conduct the following interview via email. Note that this interview was originally only available to newsletter subscribers, but since I am now offering Language Mastery Insiders a new bonus each month, I decided it was time for everyone to have the chance to enjoy Krashen’s unique brand of intellect and humor. Enjoy!

JF: Could you try to summarize the results of the research you have done over the last 30 years in a few sentences?

SK: Of course. We acquire language when we understand what we hear and read, when we understand what people are saying to us, not how they say it. To borrow a phrase from the Jewish philosopher Hillel, “the rest is commentary.”

JF: Can you provide some of the commentary?

SK: With pleasure. We do not acquire language by learning about it, by consciously learning rules and practicing them. Consciously learned rules have very limited functions: We use them to edit what we say and write, but this is hard to do, and sometimes they can help make input comprehensible, but this is rare.

We do not acquire language by producing it; only by understanding it. The ability to produce is the result of language acquisition, not the cause.

Language acquisition proceeds best when the input is not just comprehensible, but really interesting, even compelling; so interesting that you forget you are listening to or reading another language.

Language acquisition proceeds best when the acquirer is “open” to the input, not “on the defensive”; not anxious about performance.

Language acquisition proceeds along a predictable order that can’t be changed by instruction. Some grammatical rules, for example, are typically acquired early and others much later.

JF: If all this is true, what happens to language teaching? Doesn’t this mean the end of language classes?

SK: Not at all. In fact, the comprehension hypothesis makes life much more interesting for both teachers and students. Classes are great places to get comprehensible input. Even if you live in the country where the language is spoken, it is hard to get comprehensible input from the “outside world”, especially if you are an adult. The language you hear is too complex. The beginner can get more comprehensible input in one hour from a good language classes than from days and days in the country.

Here is an example from my own experience. After having spent about six weeks in Taiwan, on and off over six years, all I could say was “I like ice cream” and maybe four more words, and I understood nothing. Then in the summer of 2007 I took a nine- hour short course in Mandarin, taught by Linda Li, using TPRS, a very good method for providing comprehensible input for beginners. Linda made the input comprehensible in a variety of ways, including pictures, actions, and the use of the first language.

I got much more comprehensible input in the first 30 minutes in that class than I had in Taiwan during the six weeks I was there.

The comprehension hypothesis helps clarify what the goal of language classes is: Acquire enough of the language so that at least some authentic language input, input from the outside world, is comprehensible. Then the acquirer can improve without a class.

JF: I noticed that you said that language acquisition “proceeds along a predictable order” with some grammatical items acquired early and others late. This finding must be a big help in teaching – now we know when to teach which grammatical rules, right?

SK: That’s what I thought at first, but I have changed my position: I don’t think we should teach along any order. There are strong arguments against using any kind of grammatical syllabus.

First, we don’t know the natural order. We know enough to be confident that the natural order exists, but researchers have not worked out the order for every aspect of grammar.

Second, if our hidden agenda in a reading passage or discussion is the relative clause, or some other aspect of grammar, it is very hard to make the input truly interesting.

Third, we have to constantly review the target structures: Every language student knows that one set of exercises and a few paragraphs are not enough.

Finally, we don’t need to use a grammatical syllabus. In fact, it is more efficient not to have a grammatical syllabus. I have hypothesized that if we provide students with enough comprehensible input, the next structures they are ready to acquire are automatically provided and are reviewed regularly and naturally.

JF: I assume that translation is out of the question…

SK: Too much translation can interfere with delivery of comprehensible input. This is because there is a tendency to pay attention only to the translation and not the second language input.

But there are ways of using the first language to make input more comprehensible, including doing background reading or having discussions on topics that are especially complex and hard to understand in the second language. This is part of the basis for bilingual education: Providing background knowledge in the first language that makes second language input more comprehensible.

In class, the first language can also be used for quick explanation or for providing the meaning of a problematic, but crucial word. This may or may not help much with acquiring the meaning of the actual word, but will serve to make the entire discussion more comprehensible and thereby aid in acquisition of other words and grammatical rules. Linda Li did this very effectively in the Mandarin class I attended.

JF: This sounds nice for developing conversational language. But we also need to talk about what Jim Cummins has called “academic language.” That’s the real goal for many students of English today. Now that English has become an international language, many people need high levels of English literacy and knowledge of specialized vocabulary.

SK: Again, the comprehension hypothesis is a big help. It predicts, and predicts correctly, that there are several ways of developing academic language proficiency. The one I think is the most powerful is wide, self-selected reading, also known as free voluntary reading.

There is an overwhelming body of research that shows that free reading is the main source of our reading ability, our writing style, our “educated” vocabulary, much of our spelling ability and our ability to handle complex grammatical constructions, all important aspects of academic language proficiency.

A second way is through sheltered subject matter teaching, that is, making subject matter comprehensible for second language students in special classes, a form of “content-based” teaching.

Studies show that students in these classes typically make good progress in second language development and learn subject matter at the same time.

JF: One more question; a very important one. You have claimed that there is research supporting these hypotheses. But it is very hard to find the actual studies, especially these days when money is a problem for nearly everyone. How can we access the actual studies?

SK: I think the prices of technical books and journals are outrageous, and do a disservice to educators and concerned citizens. My approach is to make as much as possible available on the internet, for free.

I have my own website, www.sdkrashen.com, and readers of this interview are free to download, share, and cite anything on this website. I am adding articles as quickly as I can. There is already one book on the website and there will be more.

The website also has a mailing list, if people are interested in seeing short items I come across, and my own letters to the editor. I write several letters to the editor to newspapers all over the world every week. Again, readers are free to share anything from the website with others, including with their students.

We also started a free open-access internet journal a few years ago, which includes many of the research papers my colleagues and I have done, the International Journal of Language Teaching (IJFLT). Just go to ijflt.com and you have easy access. The journal emphasizes short, readable papers, a real contrast to the usual thing you see in some professional journals in education these days. And for those interested in the political as well as the research controversies in language education in the US today, I recommend two more websites which have been very important for me:

- www.SusanOhanian.org, which I regard as the center of gravity for the “resistance movement” in American education.

- www.elladvocates.org, the website of the Institute for Language and Education, a new organization dealing with policies related to children acquiring English in the US.

JF: Thank you, Professor Krashen.

]]> The latest episode of Freakonomics Radio really caught the attention of this language nerd. Titled “Is Learning a Foreign Language Worth It?“, the episode looks at the economic benefits and opportunity costs of learning a foreign language. At first glance (or rather, first listen), the economists they interview seem to make a pretty strong case against teaching foreign languages in U.S. schools:

The latest episode of Freakonomics Radio really caught the attention of this language nerd. Titled “Is Learning a Foreign Language Worth It?“, the episode looks at the economic benefits and opportunity costs of learning a foreign language. At first glance (or rather, first listen), the economists they interview seem to make a pretty strong case against teaching foreign languages in U.S. schools:

- On average, speaking a foreign language only accounts for a 2% increase in wages.

- A great deal of money and time is devoted to learning foreign languages in school that could (as some argue) be better spent on English literacy skills.

- English is (and will likely remain for some time), the international lingua franca of business.

But…

The above arguments against learning a foreign language stand on the following assumptions:

- You only learn a foreign language in a formal school setting.

- You only learn a language in an effort to earn more money.

Obviously, there are countless ways to learn languages outside of the classroom using the ever-growing pool of free (or at least reasonably priced), high-quality language learning materials, resources, apps, and crowd-sourced tools. But given the high rate of change and economic interests of traditional language education, most folks still think the only way to learn a foreign language is to plop their butts in a classroom or buy over-hyped, over-priced language products. There are certainly benefits to having access to a teacher (they can answer questions, choose tailored materials for you, and help build a cultural context), but all of these benefits can be attained with an online tutor or language-exchange partner. If you have the time or money to take classes, go for it. But don’t use a lack of either as an excuse not to learn a language.

And regarding the second assumption, external motivators like income or promotion aren’t actually very effective in the long run anyway. As an English teacher and corporate trainer, I observed that most students primarily motivated by the promise of higher pay or a position higher up the corporate latter didn’t have the necessary passion (or time!) for learning the language to show up week in and week out or put in the requisite effort outside of class. Those who excelled tended to love language for language’s sake, and looked forward to using the language to better understand and participate in the world.

One quote in the interview really stood out to me. Bryan Caplan, an economist at George Mason University, argues:

“If people are going to get some basic career benefit out of it, or it enriches their personal life, then foreign language study is great. But if it’s a language that doesn’t really help their career, they’re not going to use it, and they’re not happy when they’re there, I really don’t see the point, it seems cruel to me.”

I completely agree! But forcing students to learn a foreign language in school doesn’t mean they can’t learn them outside of school. And when one has a choice whether or not to learn a language, and what language or languages to learn specifically, it certainly provides much more personal enrichment than mandatory classes. And even better, such self-guided learning can lead to fluency far faster, far cheaper, and with far less frustration than traditional classroom-based language learning.

Here’s the show. Have a listen and let me know your thoughts in the comments.

]]>

As language learners, we’re often told that we need to memorize new words followed immediately by memorizing a phrase that uses the word. There’s no disagreeing with the important of seeing new vocabulary in context, but this method does not tell the full story of context and its power.

Some of what follows may seem a bit brainy and conceptual, but stick with me for a moment because understanding context more fully can change how you study your dream language. First off, it’s important to realize that learning words out of context is technically impossible. There is always context and you cannot learn even your first word of foreign language vocabulary without it.

Why? Because whenever you learn a new word, you’re learning it in the field of your mother tongue. Your mother tongue is a very important context because it’s like a comparative software database that sits in your brain pumping out computations every time you learn. “Maintenance” in French is like “maintenance” in English, only the sounds are different.

Or there may be limited or “false cognate” associations between two words. “Attendre” in French looks like “attend” in English, but the meaning of the words are quite different (the difference between waiting for something or someone and showing up at a concert). Either way, whether you are comparing or contrasting new vocabulary words, your mother tongue is the ultimate context in which the process of learning occurs.

Why does this matter?

Because the context of your mother tongue and understanding that this primary language is a kind of “software” installed into the foundation of your mind is where the power lies when it comes to quickly learning and memorizing new vocabulary.

Hacking Context

The language – or languages you already know – is a primary basis for association when learning foreign vocabulary. At some level your mind will always make associations, but you can hack this natural impulse by self-consciously guiding the natural capacities of your imagination using mnemonics or “memory tricks.”

A lot of people resist memory techniques for language learning because they think there’s too much work involved. Index cards and spaced-repetition software seem more concrete and direct and rote learning-based drills are deeply familiar to us from years of school.

However, what if I were to tell you that you could “download” new vocabulary words and phrases so that you can see them immediately in context quickly, reliably and even addictively?

That would be pretty cool, wouldn’t it?

Here then is an example of how you can use the context of your mother tongue to quickly learn and memorize a new word.

“Der Zug” is the German masculine noun for “train” in English. “Zug” sounds like “zoo” with a “g” at the end, so to help you memorize this, you could see a gorilla installing a “g” at the end of the word “zoo” at your local wildlife park. You would make this image large, bright, colorful and filled with zany action.

In other words, the gorilla wouldn’t just be putting the “g” at the end of “zoo” in a calm and polite manner. He’d be doing it in a frenzied manner, perhaps because the zoo police are after him (and ideally they’re about to arrive using the zoo’s train to help compound the meaning that you’re trying to associate the sound zoog/Zug with the meaning of “train.”

All of the images in this example rely upon using English, not German, as a primary context. We are playing with the foreign language word in the sandbox of my mother tongue, and if you’re playing along, you’re integrating and absorbing “der Zug” into your mind using imaginative play.

Dealing with Gender in Context

I mentioned that “der Zug” is a masculine noun. How on earth are you going to memorize this important aspect of the word with so many other images already going on?

Simple.

Put a pair of boxing gloves on your gorilla. Or anything you associate with masculinity. Maybe he’s got a cigar in his mouth, a moustache or some other stereotype (I’m sorry, but memorizing foreign language vocabulary is not place to be politically correct …)

The best part is that once you’ve chosen an imaginative indicator of gender, you can stick with it and use it again and again for every masculine word you encounter and want to memorize using a mnemonic strategy.

For some people, this might seem like a lot of work and I’ll admit that what I’m suggesting certainly isn’t a magic bullet.

But with a small amount of practice, mnemonics work gangbusters for learning and memorizing foreign language vocabulary. And if you actually found yourself using your local zoo to generate the image I’ve suggested for memorizing “der Zug,” then you will experience an interesting side-effect that you can exploit whenever you are memorizing foreign language words.

Location, Location, Location

When you try to recall the meaning and sound of this word, your mind actually knows where to go to look for images you created. This is the mnemonic principle of using a familiar location. There are ways to get even more systematic with mnemonics so that it’s even easier and more effective to memorize massive amounts of vocabulary in a very short period of time based on the principle of location, so it’s well worth looking into these special methods.

Zoog/Zug in a Phrase

Now let’s look at “der Zug” in the context of a phrase. Although you’re now going to see and memorize the word in the context of German, you will still be consciously using the context of your mother tongue to “encode” the phrase into your mind.

And let’s stick with the local zoo so that we also have the “context” of a location that will allow us to visit the mnemonic imagery we’ve created, substantially increasing our chances of recalling the sound and meaning of the phrase with ease.

“Der Zug ist abgefahren” means that the train has left the station. You can use the phrase literally or your can use it to mean that someone has “missed the boat” or that an opportunity has been missed.

You’ve already memorized “der Zug,” so it’s now just a matter of memorizing “abgefahren” (to depart). I suggest that you practice the principle of “word division” here by splitting “abgefahren” into “ab” and “gefahren.” Just as you can use a figure like boxing gloves to always remember when a word is masculine, you can repeatedly use a certain figure to remember how certain words begin.

In this case, lets use Abraham Lincoln for “ab.” The first thing that comes to my mind for “gefahren” is an image of Forrest Gump running far with the letter n tucked under his arm like a football because he’s late for the train. And Abraham helps him out by throwing the train from the zoo(g) at him so that he won’t miss it (remember, zany and weird images work best because they stand out in your mind).

Abraham Lincoln + Gump + running far with an n = abgefahren.

Der Zug ist abgefahren.

Got it.

In conclusion, I’m suggesting that you combine contexts: the context of the language itself by following up your memorization of a new word with the memorization of a phrase, but also the primary context of your mother tongue. Instead of thinking of new language learning as a process of “addition,” we can think of it as “embedding” new words like seeds into a field of rich dirt that already understands how to connect, differentiate and absorb. All we need to do is consciously manipulate our natural powers of association to bring a massive boost to our language goals.

As a final note, I’ve suggested to you some images in this article that are meant as a guide to making your own mnemonics. Because you serve as the best possible context (the movies you like, the places you’ve been, the specific ways you use your mother tongue), it’s important to draw upon your own inner resources. Relying on yourself will not only make new vocabulary words and phrases stick out like a sore thumb in the context of your mind, but drawing upon your own life will also make you more creative. The more creative you are, the more readily you can make images for memorizing more vocabulary words and phrases. Used well, context is a truly perfect circle.

The Internet has blessed modern language learners with unprecedented access to foreign language tools, materials, and native speakers. Assuming they can get online, even a farmhand in rural Kansas can learn Japanese for free using Skype, YouTube, and Lang-8. But language learning luddites and technophobes scoff at these modern miracles. Like Charleton Heston clutching his proverbial rifle, they desperately cling to tradition for tradition’s sake, criticizing these modern tools—and the modern methods they enable—from their offline hideouts. Communicating via messenger pigeon and smoke signals no doubt…

“Technology is for for lazy learners!” they exclaim. “Real language learners”, they insist, use the classroom-based, textbook-driven, rote-memory-laden techniques of old.

I call bullshit.

Given how ineffective these traditional methods and materials tend to be for most learners, I can only assume supporters do so from a place of masochism, not efficacy. Perhaps they feel that the more difficult their task, the more bad-ass they become if they manage to succeed despite less-than-optimal methods, materials, and tools.

These voices seem to be loudest in Japanese and Mandarin Chinese language learning circles, which should come as no surprise since these two languages are often considered “extremely difficult” and teachers of these languages tend to be most stuck in tradition and unwilling to embrace change. Personally, I don’t consider any languages difficult per se. Just different. This may be mere semantics, but one’s attitude toward a language plays a major role in one’s ability to stick with it long enough to reach fluency. Think about it: even supposedly “difficult” languages like Japanese, for example, pose many advantages for native speakers of English, including:

- A massive head start in vocabulary acquisition. Japanese contains a mother load of English loan words. When in doubt, just pronounce an English word with Japanese pronunciation and changes are good you will be understood. If that fails, just write down the English word on a piece of paper and they are likely to recognize it. Why? Throughout middle school, high school, and university, Japanese students must memorize thousands of English words, but the focus is on reading and spelling, not spoken English. So most folks can recognize English words when written down but probably won’t register the same word spoken aloud. Yet another reason why traditional language education approaches fail…

- Few new sounds & one-to-one pronunciation. English speakers already know how to make nearly all the sounds in Japanese. You just have to learn the Japanese ‘r’ and ‘ts’ sounds. Also, each kana in Japanese can only be read one way, unlike English letters—for example, English’s notorious ‘e’—that can represent numerous sounds.

- No need to change verbs based on the subject. Unlike most European languages, Japanese does not inflect verbs to agree with the subject pronoun. “I go”, “You go”, “We go”, “They go”, “He goes”, and “She goes” are all ikimasu (行きます・いきます).

But the linguistic masochists of the world don’t want to talk about such advantages because it threatens their egos and their “I study hard therefore I am” ethos.

There’s nothing wrong with studying your butt off. But make sure your efforts are applied to methods that actually work like spaced repetition systems, imaginative memory, mnemonics, and pegging, and materials you truly enjoy like podcasts, YouTube, blogs, anime, and manga. Why cling to expensive, outdated methods when free, modern options exist?

]]> Have you been studying a language for a few months, years, or even decades, but aren’t seeing any noticeable progress?

Have you been studying a language for a few months, years, or even decades, but aren’t seeing any noticeable progress?

First of all, make sure that you’re using a good way to measure your actual—as opposed to perceived—progress. I suggest recording an unrehearsed audio or video diary at least once a week, and writing a daily journal. Both of these active output tasks are far better measures of your fluency than multiple choice tests, and best of all, encourage you to do the very tasks that lead to conversational fluency.

Assuming your progress tracking tools are not the issue, here are five likely reasons you’re not improving as quickly as you’d like:

1) You’re not putting in the requisite hours each week.

The most common reason we fail to progress in any skill based endeavor is that we simply don’t spend enough time on task. It’s all too easy to log in 40 hours a week marathon viewing Breaking Bad, but how many hours a week do you honestly spend hearing, speaking, reading, and writing your target language? As an experiment, jot down how many minutes or hours you spend studying or immersing in a language each day for a week and then tally up your results. Even the most diehard learners may be surprised how little they spend each week. This is but one of the highly under-appreciated components of child language acquisition. They have no choice but to immerse in their first language throughout the day, and end up spending an enormous amount of time in their first few years of life sucking up the language around them. Before you say “children are better learners than adults”, try spending the same number of hours they do actively acquiring the language. If you did, I bet you’d learn even faster than the little ones.

2) You’re spending too much time reading and not enough time listening and speaking.

Although reading skills are extremely important, many learners (especially highly educated adults) fall into the cozy trap of reading far more than listening or speaking. I get it. Reading is safe. There’s no messy two-way communication to deal with. No chance that people won’t understand you, laugh at your mistakes, or give you chicken feet when you wanted fried chicken. But realize that reading does very little to improve your listening and speaking skills. You’ve probably encountered non-native speakers of English who can read The New York Times without much difficulty but can barely order a coffee to go along with the paper.

3) You’re not engaging in “deliberate practice”.

Podcasts and YouTube are great, but passive input alone is not enough. To make quick, tangible progress in a language, you have to engage in deliberate practice every day:

- Stay on target. Deliberate practice requires a high level of motivation and intense, constant focus on your specific goals. If your goal, for example, is to be conversationally fluent in 3 months, ignore (or at least minimize) reading and writing tasks for now until you’ve reached your objective.

- Get immediate feedback on your performance. Deliberate practice requires immediate feedback on your performance in the language. Have your friends, tutors, or teachers jot down mistakes you make and go over them one by one once you finish your sentence.

- Repetition, Repetition, Repetition. Deliberate practice requires that you get repeated exposure to the same words, kanji, phrases, structures, topics, etc., especially those that prove most difficult for you. If you already know something frontwards and backwards, there’s no reason to waist valuable time reviewing it again. Spaced repetition systems (SRS) like Anki and Memrise are a great way to automatically schedule reviews based on difficulty and the time since your last exposure, but just like the reading trap I mentioned above, make sure that you are not spending more time doing Anki reps than you are actively listening and speaking your target language.

4) You’re not hungry enough for it.

Aside from using archaic methods and boring textbooks, there’s a major reason why most folks don’t learn much in their high school Spanish class: the class is mandatory. If you had been given the choice to learn more “exotic” sounding languages like Japanese or Chinese in school, I bet you would have been more motivated to learn and retained much more of what you studied. Choice is a powerful motivator. I’ve taught thousands of adult English learners over the past 10 years, and have observed two overarching trends:

- Even after years of study, students in mandatory English classes (whether at school or work) seldom make any real progress.

- Those who did excel had strong internal motivation. Even if they didn’t have to learn English or weren’t offered free classes by their company, they would have chosen to do so at their own expense.

5) You don’t have a clear purpose for learning the language.

While there’s nothing wrong with learning a language just for spits and giggles, you probably won’t progress very quickly if you’re just learning as a casual pastime. If you’re serious about making rapid progress, you must make the language your top priority, and create extremely “S.M.A.R.T.” (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-bound) goals. “I want to be fluent in Japanese”, for example, is not such a goal:

- It’s not specific. “Fluency” is a very broad concept. Do you mean oral fluency or literacy? Do you mean fluency in a wide range of topics or just for your specific professional needs and personal interests?

- It’s not measurable. Not only is “fluency” difficult to define, but it’s also extremely difficult to measure. Sure, you can use standardized tests like the JLPT (Japanese Language Proficiency Test), but it is better at measuring your test taking ability and how much information about Japanese you’ve memorized, not your actual ability to use it day to day.

- It’s not attainable. If something can’t even be defined or measured, then how can you ever attain it?

- It’s not relevant. This goal is so large and vague that it has little impact on the day to day activities required to improve your fluency in Japanese.

- It’s not time-bound. There is no finish line in languages. Even native speakers continually expand their vocabularies and refine their communication skills, so by definition, this goal is not time bound is therefore not helpful for our purposes.

Photo courtesy of Ivana Vasilj via Flickr Creative Commons

Charlemagne, also known as “Pater Europae”, famously said:

“To have another language is to possess a second soul.”

Beyond the soul, languages are good for the mind, too. A 2011 article published on Livescience.com showed that learning a new language can protect our brains from developing Alzheimer’s disease, improve cognitive skills, and keep our minds sharp.

The good news: Thanks to the latest mobile technologies, language barriers are starting to fall. Google Translate’s Phrasebook, for example—a highly-recommended application by Verizon—facilitates communication and helps people learn and remember useful foreign phrases.

The bad news: Despite the neural benefits of learning a foreign language and the many advances in language learning technologies, most people still struggle to learn languages, held back by the myths like “only children can learn a foreign language well”.

In this article, we’ll bust the age myth, along with four other frequent offenders.

Myth 1: “I’m too old to learn a new language.”

People usually think that kids have more flexible brains, which can soak up more information than adults. This is a myth. According to many studies, adults can actually learn new languages more efficiently than children. Thanks to the adult’s mature learning system, they can understand complex grammar structures and memorize new vocabulary far more quickly. It’s never too late to learn something that can help enhance your life.

Myth 2: “Mistakes don’t matter.”

Committing mistakes is a natural, unavoidable part of the learning process. Moreover, you will usually still be understood even with grammatical mistakes if your pronunciation is good and there is a clear context. And even if they don’t understand you, they will appreciate your effort.

But this doesn’t mean you shouldn’t strive to fix your mistakes. One of the best ways to improve mistakes is to record yourself talking about a particular topic or event, and then have a native speaker transcribe what you said, highlighting mistakes in your grammar, vocabulary usage, and pronunciation.

Myth 3: “I’m not a fast learner.”

Everyone has their own set of learning curves, and it’s true: learning a new language can be “challenging”, though not necessarily “difficult” if done correctly. In the past, teachers used older methodologies that made adult students more anxious and less motivated to learn new things. But thanks to modern teaching techniques, anybody can learn a significant amount of functional language in a few weeks or months.

One such technique is mastering a small set of basic phrases first. For example:

“I’m sorry.”

“Excuse me.”

“Do you speak English?”

“Where is the bathroom/toilet?”

“I understand. / I don’t understand.”

These examples represent many of the top 100 words, which are frequently used in everyday conversations.

Myth 4: “You will learn a language automatically by living abroad.”

While immersion is an essential part of learning a foreign language, the fact is that living in another country alone won’t automatically turn you into a fluent speaker. Some immigrants to the Unites States, for example, have learned that just living in an English speaking country isn’t enough to transform them into fluent English speakers. Without concerted effort, living in a foreign country will likely only lead to mastery of very basic phrases you need to survive, broken sentences, and bad grammar.

On the other hand, with enough effort, you can immerse yourself in language right here in your home country. If you’re learning Japanese, for example, look for a native speaker in your own area who can really teach you. Watch foreign movies or television programs to practice your listening skills. Practice speaking and writing until you reach conversational fluency, and then go abroad to polish your skills and aim for native-like fluency.

Myth 5: “English is the language of the world. Learning a new one isn’t important.”

Only 5% of the world population speaks English, while 95% speak another language. Learning another foreign language, aside from English, is recommended and it can be a fulfilling experience. It helps you understand different cultures, keeps your mind engaged, and you become an asset to your workplace.

As the world becomes more digitally connected, we become more exposed to different languages. From the comfort of your own home, you can easily learn a new language through the Internet, television, and even books. In the end, you’ll gain more and be able to connect with other cultures.

]]>The following guest post is by Matthew Pink, a writer and editor working in digital publishing. He covers topics including media education, music and sound. You can find out more about his work and his new crime e-novel ‘Scafell’ at www.matthewpink.co.uk

Learning languages is a multi-faceted process. Nowadays they would probably call it holistic. Or 360. Or something.

But what I mean is that there are many different channels you can use to absorb the language which then enable you to reproduce it when the situation requires.

There is the bread and butter of vocabulary learning which you simply have to integrate into your daily routine. There is grammar and syntax to think of – this is best taught and then practised until trial and error gets you to a place where you can slip clause A into hole B with confidence. Then there is form and function to mull over – when is it appropriate to use what tone and what style of formality. Then of course there is pronunciation to consider – making sure you are understood.

Naturally these different facets are variously served by blends of active and passive learning.

Through the passive consumption of audio content (as it is now so-called), language students can absorb all these different facets through listening and comprehension exercises. These exercises, if structured correctly to include active task-based learning, are a great way to consolidate and strengthen the base layer of knowledge of the target language.

However, I actually want to propose a method which turns this on its head a little bit and make a case for an active learning task which I have found particularly useful in the past. This is the production of a short radio drama through a short workshop (a little like this one). This was an especially stimulating exercise for me because it combined so many of cultural passions – sound, music, drama and speech. When you can harness a student’s interests to language learning, you often find it to be the most dynamic and productive of learning periods.

Let me set the scene a little bit.

In our particular case we were given the outline of a situation ripe with conflict – an awkward dinner party conversation between a father and his teenage daughter where the overly defensive mother is also present and trying to mediate between the two firebrands of her family.

We had to put together a 5-10 minute sketch in the target language which would work as a piece of radio drama. The facilitator gave us a box of goodies with which to create whichever sound effects we would need to create to accompany the awkward conversation. We were to create the piece together, rehearse, and then record it for reference.

Firstly, between the 3 of us, we thought how the conversation might pan out between the father and daughter. We decided that the daughter was going to tell her father over dinner that she was pregnant by her boyfriend (of whom her father was not keen at all). There was to be some skirting around the subject by the daughter, some awkward silences, some tension-raising screeches of glasses and scuffs of chairs on the floor and then finally an explosion of rage from the father which we wanted to cut off just as the detonator went off (for effect).

We then noted this down in rough form in the form of a rough script, allocating one character’s voice to each of us and we imagined what we might say in that character’s position.

Where we could we tried to write the script in the target language but mostly we wrote in our native tongue and then translated afterwards. This seemed to work well.

Interspersed between the lines of dialogue we were instructed to use sounds to replace the ‘unsaid’ where the answer to a question might not be a directly verbalised response but instead the shifting of a glass, a nervous cough, or the scrape of a chair.

We then rehearsed and, from the practice session, we were able to edit the sections which didn’t work. On top of this we improved and honed the translations to make them more realistic.