by John Fotheringham

Just as the printing press democratized access to the written word, ebooks are again revolutionizing how information is produced, distributed and consumed. Even successful authors, whose very livelihoods have depended on the sale of dead-tree books (e.g. Timothy Ferriss, author of The 4-Hour Workweek and The Four-Hour Body, and Seth Godin, author of Tribes, Permission Marketing, and All Marketers are Liars) have seen the writing on the literary wall, and agree that “print is dead”, or at least “dying fast”…

Here are a few reasons why the ebook is beating print books to a “pulp” (pun intended):

- Lower Production & Distribution Costs: This allows for lower retail prices, putting books in the hands of more and more readers. And many ebooks are available at no cost at all, including literary classics no longer covered by copyright (e.g. Project Gutenberg) and new works that are free by choice (this is one of the common “freemium” strategies where an ebook is used for free marketing to promote other paid content or services.)

- Read Anytime, Anywhere: You can literally carry thousands of ebooks with you on your mobile device or ebook reader. Language learning is then just a click away whether you are on the bus, a plane, or bored to tears in a meeting. And if you forgot to download books at home, you can always download more on the go via WiFi or even 3G networks.

- More Time Efficient: Many ebook readers allow you to easily cut and paste words and even look up unknown terms using built in dictionaries. This can save the learner hours and hours, especially in ideographic languages that usually require looking up characters by strokes, radicals, or handwritten input.

So now that I’ve made the case for ebooks, let’s look at my two favorite weapons of choice for using ebooks in foreign language learning:

Best Ebook Readers

There are heaps of ebook reader devices on the market today (the Amazon Kindle, the iPad, the Sony PRS series, the Barnes & Noble Nook, etc.), as well as numerous ebook reader apps available for Android devices, iPhones, iPads, iPod touches, Blackberry devices, PCs and Macs. After trying out hundreds of different devices at last year’s CES and stealing…I mean “borrowing”…a few of my friend’s devices for further testing, here are my two finalists:

1st Place: The Amazon Kindle 3G

Price:

- Kindle 3G: $189 USD

- Kindle (WiFi version): $139 USD

Where to get ‘em: Available from Amazon.com

While I am a full-fledged Apple fanboy, I must give Amazon credit where credit is due. Despite serious competition from the Apple iPad, Sony’s various ebook readers, and myriad other me-too products, the Kindle remains a hot seller, and my humble opinion, the world’s best ebook reader.

Here’s what I love most about the Kindle:

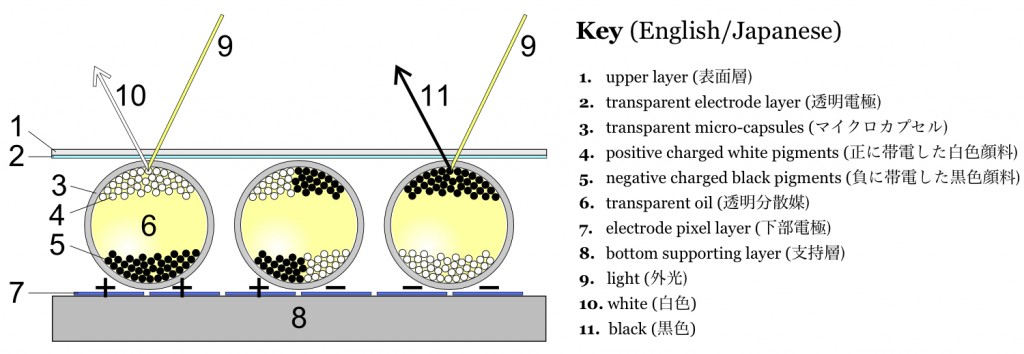

1) E ink is easy on the eyes and your battery. Unlike the pixels used on computers and smartphones (which can wreak havoc on your eyes and zap your battery), the Kindle’s use of E Ink creates a reading experience pretty darn close to physical books, all while consuming very little battery life. They accomplish this amazing feat by employing millions of itsy-bitsy, electronically charged “microcapsules”, within which there are tons of little black pigment pieces and white (or rather, light gray) pigment pieces. Text is produced by causing the black pigments to run to the top of specific microcapsules, while the background is created when the gray pigment is forced to the top. The Kindle display is also much easier to read outside in the sun, while most other devices (including the iPad, iPhone, and iPod touch) suffer from serious glare problems.

2) Direct access to the world’s largest book store pretty much anywhere in the world. Users can wirelessly access over 750,000 ebooks, plus heaps of audiobooks, newspapers, magazines and blogs, in over 100 countries worldwide. And unlike the iPad, the 3G wireless connectivity is provided free of charge.

3) Great Apple and Android apps. If you don’t want to fork over the funds for a Kindle, or you already own one but don’t feel like lugging it around all the time, you can always just download the Kindle app.

Download the free Kindle app (Android, Apple iPhone, iPad, iPod touch, Blackberry, PC, or Mac)

2nd Place: iBooks on the Apple iPad, iPhone & iPod touch

Prices:

- iBooks: free download in iTunes

- iPod touch: $229 USD (8GB), $299 (32GB), and $399 (64GB)

- iPad (WiFi): $499 USD (16GB), $599 USD (32GB), and $699 USD (64GB)

- iPad (3G): $629 USD (16GB), $729 USD (32GB), and $829 USD (64GB)

Where to get ‘em: Apple retail stores, the Apple Online Store, Amazon, Target, WallMart, AT&T Stores, Verizon Stores (iPad is available now; iPhones will allegedly be available through Verizon in early 2011…).

1) More than JUST an ebook reader. My only gripe with the Kindle is that it is only an ebook reader. With the iPad, iPhone, or iPod touch, on the other hand, your device is only limited by the apps you download to it. I currently have about 100 hundred apps on my iPod touch, including Skype for calling tutors and language partners, Evernote for keeping notes of new words and phrases, iLingQ, ChinesePod, SpanishPod, and on, and on, and on…

2) Sexy, intuitive user interface. The Kindle interface isn’t bad by any measure, but it pales in comparison to the rich, elegant design of Apple iBooks. The new “retina display”, available on the iPhone 4, iPod touches (4th gen), and likely the next vesion of the iPad, creates extremely crisp, vivid images, and makes reading text far easier than on lower resolution devices.

3) Excellent built in dictionary, bookmarks, highlighting and search features. iBook’s built in dictionary, bookmarks and highlighting tools are a thing of beauty. To look up a term, you need simply tap the word and then click “Dictionary” from the pop-up menu. To highlight, you again just tap a word and then drag the handles to the left or right to select the words or sentences you want. Bookmarking requires just a quick tap in the upper right corner. Best of all, you can then quickly go back to your saved highlights or bookmarks using the table of contents tab. Also, you can use the search feature to quickly find all instances of a particular word (a very useful feature for language learners as it allows you to quickly see how a particular word is used in context.)

Getting the Most Out of Ebook Readers

As we’ve seen, ebooks and ebook readers are wonderful language learning tools indeed. But as ESLpod’s Dr. Jeff McQuillan puts it, “A fool with a tool is still a fool.” Here then, are some tips on how to best apply these amazing new tools.

1) Don’t fall into the trap of reading more than you listen. Reading is an important part of language acquisition, and is an essential component of learning how to write well in a foreign language. But remember that listening and speaking should be the focus of language study, especially in the early stages of learning. It is all too easy to spend too more time with your nose in a book than listening to and communicating with native speakers, especially for introverts and those who have been studying for too long with traditional, grammar and translation based approaches.

2) Read an entire page before looking up unknown words. Lest you get distracted and lost in the details, I suggest making at least one full pass through each page in your ebook before looking up unfamiliar words.

3) Choose books that are just a tad beyond your comprehension level. By “comprehensible” I mean that you can understand about 70 to 85% of the text. Too far above or below this and you will quickly get bored and likely give up.

4) Use the Kindle’s Text-to-Speech Tool. The Kindle and Kindle 3G can literally read English-language content out loud to you. Use this feature when you are doing other tasks that require your vision but not your ears, and as a way of building your listening comprehension. I suggest listening to a passage first and then reading to back up your comprehension.

5) Get audio book versions of ebooks you read. While the Kindle’s text-to-speech tool works well, it can get a bit monotonous with its robotic pronunciation. For longer books, I suggest buying the audio book version the book, which tend to be read by professional voice actors, and are therefore far easier to listen to… Audio books are available from Audible, iTunes, and countless other site, and make sure to check out the free Audiobooks app for the iPhone, iPad and iPod touch.

]]>Antonio is an applied linguist, and martial arts and adventure author living in Asia (check out our interview with him here). His books, including ”The Monk from Brooklyn”, are available at Amazon.com.

When I started my Vietnamese intensive course, a lot of non-linguistists I talked to said that the Chinese students would have an advantage because they already speak a tonal language.

It is true that some Westerners could be completely stumped by tones, and just not get the language at all. But, a person who already speaks a tonal language does not have an advantage over a Westerner or a Korean or Japanese who is intelligent, motivated and who is trying to learn tones. Remember that a Cantonese or Mandarin speaker has mastered the tones of his or herlanguage, not the tones of Vietnamese. Saying that someone from a tonal language would have an advantage is like saying people from languages with words, or sounds, or verbs or adjectives would have an advantage.

Mastery of a particular language is based EXCLUSIVELY on your mastery of THAT language, not other languages. If you know tones in one language, you still need to learn the specific tones for the new language you are studying.

Next, people who were more language-savvy suggested that both the Chinese and Korean students would have a huge advantage because of all of the Chinese cognates between Chinese, Korean and Vietnamese. But in my class, I have noticed the Chinese and Koreans don’t even hear or notice the cognates. I help Schwe Son translate his homework every single day and he never sees the cognates. The Koreans are the same.

In addition to not having a particular advantage, our Chinese classmate, Schwe Son (not his real name) seems to have a number of special problems because of his Chinese mother tongue. For example, we learned the words for “half a million.” But in Chinese, there is no word for a million. They count by ten-thousands. So, a million is 100-ten-thousands. Schwe Son pointed at the Vietnamese words for half a million, nửa triệu, and asked me to translate. I translated it into Chinese, literally, “Half of 100-ten-thousands.” The look on Schwe Son’s face was as if he had just seen me defecate in a frying pan. “Why don’t they just say 50-ten-thousands?” He asked. He had a point.

The old Vietnamese word for Burma is ‘Miến Điện’ the same as in Chinese. But now the Vietnamese have created a Vietnamese spelling for the countries new name of Myanmar. Most languages and most countries move toward not changing country or city names, but just spelling them in their own language. This is why Beijing is now Beijing in English, instead of Peking. But Chinese cannot move in that direction, as it is impossible to spell foreign words with Chinese characters. As a result, many Chinese place names are outdated. Or, they have to create a totally new word, which may or may not be recognizable as the place it relates to.

So, in class, when we encounter country names that are instantly recognizable for Western or Korean students, but for which Schwe Son needs a translation. Afterwards, the translation has no real meaning for him. He just has to memorize it, although it doesn’t relate to anything.

We have only had eight days of class so far, but have already encountered a lot of Chinese cognates. The word for ‘a shop’ which I learned in Hanoi was ‘cửa hàng’. But here in Saigon they say ‘tiệm.’ this is a cognate from the Chinese, ‘Diàn’. And yet, when we came to this word, Schwe Son asked me to translate. I said, in Chinese, “tiệm means Diàn.” Schwe Son simply said, “OK.” And immediately wrote the Chinese character in his notebook. There was not even a flicker of recognition.

Here is a list of Chinese cognates from the first eight days of class (I have only listed modern Mandarim cognates. If I were to list ancient Chinese cognates (similar to Korean and Cantonese cognates) the list would be much, much longer.)

| English | Vietnamese | Chinese Pronunciation | Chinese Character |

| Please | xin | Qǐng | 請 |

| Shop (n) | tiệm | Diàn | 店 |

| South | nam | Nán | 南 |

| East | đông | Dōng | 東 |

| come | đi lại | Lái | 來 |

| Zero/Empty | Không (zero) | Kōng (empty) | 空 |

| zero | linh | Líng | 零 |

| prepare | Zhǔnbèi | chuẩn bị | 準備 |

| money | tiền | Qián | 錢 |

| side | bên | biān | 邊 |

| Café | quán cà phê | Kāfēi guǎn | 咖啡館 |

| wrap | bao | Bāo | 包 |

| pronunciation | phát âm | Fāyīn | 發音 |

| dictionary | tự điển | Zìdiǎn | 字典 |

| Burma | Miến Điện | Miǎndiàn | 緬甸 |

| Country | Quốc gia | Guójiā | 國家 |

| Germany | Đức | Déguó | 德國 |

Vietnamese is a Mon-Khmer language, in spite of having so many Chinese cognates. Chinese is a single syllable language, with a lot of compound words. But Mon Khmer languages have multi-sylabic words. The Chinese student is having a lot of difficulty with the pronunciation of multi-sylabic words.

Possession in Khmer, Vietnamese, and English can me made, using the verb, “to belong to”, as in, ‘the book belongs to me.’ But most languages don’t have that construction. Neither Korean nor Chinese has it. (It exists in Korean, but no one uses it). So, they were all having a hard time understanding the concept of, “book belongs to me”, “sách của tôi”. The Chinese student kept pushing me for word-for-word translations. But obviously, there was no way to translate this word-for-word. I could only translate the meaning. In Chinese, “This is my book.” But then he would flip the book to the previous day’s lesson. “I thought this phrase meant ‘this book is mine’.” He said. “Yes,” I said. “The meaning is the same, but the wording is different.” “OK, so what is it in Chinese?” he asked again.

Schwe Son realizes he needs to improve his English in order to get through his study of Vietnamese language. So, every day, in addition to translating his homework into Chinese, he asks me to translate it into English for him. And this creates a whole other set of problems.

In Vietnamese there is a word for the noun, “a question” (câu hỏi), and the verb “to ask” (hỏi) is a related word. The noun, “answer” (câu trả lời) is also related to the verb “to answer” (trả lời). But in English, obviously, the verb “to ask” is unrelated to the noun “a question.”

“Open and close your book” in Vietnamese is exactly as it is in English. Meaning the same words “open and close” could be used for the door or a drawer or a crematorium. But in Chinese, the words for “open and close your book” are unrelated to “open and close the door.” I translated for him, and he understood what the phrase ‘open your book meant’ in Chinese, but it was a completely unrelated phrase, that had no meaning and no connection to anything else for him. For the rest of the classmates, once they learned ‘open and close’ they could apply it to anything. But for Schwe Son it was one isolated piece of linguistic noise.

There are so many aspects to learning a language: vocabulary, grammar, pronunciation, usage, and many more. Though an argument could be made that a student with a given native tongue may have an advantage in one area, he or she may have other areas with particular difficulties.

]]>This tome of language awesomeness contains over 500 pages of language learning advice, tips, and success stories, with contributions from 43 authors, including Moses McCormick, Steve Kaufmann, Benny Lewis, Stuart Jay Raj, and countless others language heroes.

The book is the brainchild of Claude Cartaginese of Syzygy on Languages, who also edited the work. In his own words, The Polyglot Project is:

“…a book written entirely by YouTube Polyglots and language learners. In it, they explain their foreign language learning methodologies. It is motivating, informative and (dare one say) almost encyclopedic in its scope. There is nothing else like it.”

And here is an entertaining video announcement about the book’s release from Claude:

Buy “The Polyglot Project” on Amazon

Download a free PDF of “The Polyglot Project”

Download my chapter of the “The Polyglot Project” (I fixed some typos that made it into the book…)

]]>

As a language learning addict, I follow lots (and I mean lots) of polyglot blogs and podcasts. It is always interesting to see what has worked (and what hasn’t worked) for successful language learners. While most fluent foreign language speakers tend to agree on the vast majority of language learning DOs and DON’Ts, there is one area that always seems to cause heated debate, shouting, name calling, and occasional mud/poo flinging: the importance of language input (i.e. listening and reading) versus language output (i.e. speaking and writing).

I have sat quietly on the sidelines for some time now, politely listening to both sides of the argument. But it’s time to blow my referee whistle because both teams are “offsides” (Okay John, enough sports analogies already!)

The Argument is Flawed to Begin With…

The problem with the whole argument is that input and output are not mutually exclusive components of language learning. You need both. The key is order and balance.

1. Listen first, then speak

When just starting out in a language, it is important to get as much listening input as possible. Just like when you learned your first language, you need to first go through a “silent period” where your brain gets used to the patterns and phonology of the language. Once you have filled your teapot up with enough listening input, language will naturally want to start pouring out. That’s when it’s time for a tea party to put into practice what you have assimilated (and no, I am not promoting that kind of “tea party” as I am a bleeding-heart liberal…)

When just starting out in a language, it is important to get as much listening input as possible. Just like when you learned your first language, you need to first go through a “silent period” where your brain gets used to the patterns and phonology of the language. Once you have filled your teapot up with enough listening input, language will naturally want to start pouring out. That’s when it’s time for a tea party to put into practice what you have assimilated (and no, I am not promoting that kind of “tea party” as I am a bleeding-heart liberal…)

But unlike little babies, adults can also rely on reading input to back up what we listen to. This difference (along with the fact we don’t have to wear diapers) gives adults a major leg up on babies learning their first language.

To this end, try to find short, simple dialogues of actual native speakers with transcripts. Then listen and read, listen and read, and listen and read again as many times as your schedule and sanity allow. My personal favorite transcript-equipped podcasts are produced by Praxis Language (ChinesePod, SpanishPod, FrenchPod, ItalianPod and EnglishPod) and LingQ (English, French, Russian, Spanish, German, Portuguese, Italian, Korean, Chinese, Japanese, and Swedish). I can’t stand the overly stilted, monotonous dialogues found on most textbook companion CDs and suggest you avoid them like the plague.

2. Take equal doses of your input and output medicine.

Once you have gone through your silent period (which will be input-centric by definition), try to spend an equal amount of time on input activities (listening to podcasts, reading blogs, etc.) and output activities (speaking with friends or tutors, writing a blog post in the foreign language, etc.). It may be nerdy, but I literally use the stop-watch feature on my iPod touch to time my input and output activities each day…

If you follow the above regimen, your foreign language skills will progress quickly, efficiently, and most importantly, enjoyably. However, if you follow the advice of the extremists on either side of the input-output debate, you are in for heaps of problems and a world of pain. Here’s why:

Output Only Problems

Proponents of the “Output is awesome; input is lame” philosophy suggest that learners just “get out there and start communicating with native speakers”. This approach, while certainly sexier than what I prescribe above, has a number of problems:

1. Nasty mispronunciation habits.

Bad pronunciation habits develop when you pronounce things how you think they should be pronounced based on your overly limited listening exposure to the language, and your logical, but nonetheless incorrect, assumptions based on how words are spelled but not pronounced.

2. You’ll be that annoying guy at the bar.

Because you have a limited vocabulary and only understand little of what is said to you, you will likely attempt to control conversations by keeping them on topics you are familiar with, using phrases and vocabulary you have memorized. All but the most patient interlocutors will get bored or annoyed by such one-sided conversations. Don’t be that guy.

3. You probably won’t enjoy the process and give up early.

Many would-be language learners give up because they simply don’t enjoy the process. Much of the angst, tedium and phobias stem from having to speak before one is ready. Language teachers are the worst perpetrators, presenting you with new words or phrases one minute, and then expecting you to actually use them the next. Well-meaning friends or language partners are no better, trying to “teach” you new words and phrases and expecting that you can actually use them right away. Assimilation takes time and repetition, so don’t beat yourself up if it takes a few times (or a few hundred times) of hearing or reading a new word or phrase before you can actually use it.

Input Only Problems

If, however, you spend months and months diligently listening to your iPod and reading online newspapers, but never actually speaking with native speakers (by design or chance), you will understand quite a bit of what goes on around you but will struggle to actually verbalize your thoughts well or have natural exchanges with native speakers. This happens because:

1. Proper pronunciation is a physical feat.

You can’t think your way through pronunciation (believe me, most introverts have tried and failed!). Good pronunciation requires that your ears first get used to the new language (i.e. through getting lots and lots of listening input), and then also getting your lips, tongue and larynx used to new sounds not found in your native tongue, which of course takes lots and lots of talkin’ the talk.

2. Speaking and writing identifies your learning gaps.

Until you actually try to say or write something, you won’t know what you really know. While you may passively recognize certain words, phrases, idioms or Chinese characters, you may still struggle to say or write them. This is even true for your native language (as I found out when I first started teaching English and was confronted with such conundrums up at the white board as “Wait a second…How in the hell do you spell “misspelled”?)

The more you speak and write, the more you know where the “holes” are in your language cheese, and the easier it will be to fill them with focused study and review.

Conclusion

So as in all things, the extremists tend to be just that: extreme. They tend to get more attention, but the efficacy of their advice tends to be an inverse proportion to their popularity…

To become fluent in a language, just consume a balanced diet, rich in listening and speaking, with plenty of reading and writing sprinkled in for flavor.

]]>

I often hear English learners and English native speakers alike complain that certain English words are “difficult” (in fact, I’ve heard the same thing said by native and non-native speakers of Japanese and Mandarin Chinese, too).

Consider the words shoe and happy. Are these English words difficult? To you and I, these terms are probably as easy and basic as they get. But what about for a 6-month old American child? Or what about for a hunter-gatherer living deep in the Amazonian rain forest who has never heard a word of English spoken or seen any English writing? For both, all English words are more or less “difficult”, or rather, “unfamiliar”.

And that right there gets to my basic contention. There are no “difficult” words in English or any human language; there are just those words that are familiar, or as of now, unfamiliar to you.

Consider the words vapid and insipid. If you are well-read or have just studied for TOEFL, you are probably familiar with the words and would not consider them “difficult”. But if you were to poll the average American high school student, they would probably not know the meaning of either word despite the fact that neither represent advanced cognitive concepts (and in fact have the same basic meaning of “bland, flat, dull or tedious”), have few letters, and are easy to spell. These words aren’t difficult; they are just uncommon and therefore perceived as difficult to the uninitiated.

I do concede, however, that there are some words that are difficult to pronounce in certain languages. One prime example came up yesterday as I was discussing different types of cars with my girlfriend (she has just moved to Seattle and is quickly realizing how lame our public transportation system is compared with Taipei…hence the need for a car). I was explaining the pros and cons of front wheel drive cars and rear wheel drive cars, when I suddenly realized what a mouthful “rear wheel drive” is when said many times fast in quick succession. The combination of r’s, l’s and w’s requires quite a bit of tongue and lips movement and can quickly wear out the mouth muscles. Similar challenges are experienced by Mandarin Chinese learners when trying to wrap their mouths around “retroflex” sounds like [tʂ] (zh), [tʂʰ] (ch), and [ʂ] (sh), that require bending the tip of the tongue back towards the top of your mouth.

But meaning, not pronunciation, is usually what people refer to when they call a word “difficult” (and as I make the case for above). In reality, however, it is not actually the meaning that is the problem, but rather learning the myriad arbitrary connections between meanings and sound combinations in any given language. And the only way to make these connections stick is through lots and lots of listening, supported by lots and lots of reading.

]]>Antonio Graceffo is an applied linguist and martial arts and adventure author living in Asia (check out our interview with him here). His books, including ”The Monk from Brooklyn”, are available at Amazon.com.

A Khmer student wrote to me on youtube and asked me to produce videos about how to read English language newspapers.

A Khmer student wrote to me on youtube and asked me to produce videos about how to read English language newspapers.

“I’d like to ask you to make videos how to read newspaper and translate it from English to Khmer. I Khmer and I having a problem to understand English phrases.” Wrote the student.

Language learners often write telling me about some area of learning or area of their lives where they are experiencing difficulties of comprehension and ask me for a trick or a guide to help them learn.

As I have said in numerous other language learning articles, there are no tricks and no hints. The more hours you invest, the better you will get. And if your goal is to read at a native speaker level, then you need to read things a native speaker reads. If you are a 22 year-old university graduate, then you need to be reading at that level in the foreign language. And you won’t get there by reading textbooks ABOUT the language. You will get there by reading books, articles, and textbooks IN rather than ABOUT the language.

If we analyze this latest email, the student says he has trouble reading, and he specifically singled out newspapers.

Obviously, reading is reading. On some level, reading a newspaper is no different than reading a novel or reading a short story.

If you are reading novels and short stories, you should be able to read newspapers. If I asked this student, however, he is probably is not reading one novel per month in English. If he were, newspaper reading would just come.

Therefore, the problem is not the reading or the newspapers, per se. The problem is the lack of practice.

I never took a course called “Newspaper Reading” in English. I just started reading newspapers. And at first, I had to learn to deal with the language, structure and organization of newspaper writing, but no one taught me, or you. It just came to us. The same was true for German or Spanish newspapers which I can read almost as well as English. No one taught me, or taught Gunther or Pablo, it just came through practice.

A point, that I have made many times in articles, is that when you begin learning a foreign language, you are not an idiot. You are not starting with an empty brain. One reason it takes babies three years to learn their native tongue is because they are also learning what a language is and how language works. You know all of that, and much more. Babies don’t know that there is such a thing as grammar. Every single piece of vocabulary has to be learned. A seven year old may not know the words “population, economy, government, referendum, currency” in his native tongue. So, reading a foreign newspaper would be difficult for him, because reading a newspaper in his mother tongue is difficult for him.

If you are an adult, coming from a developed country, with at least a high school or university level of education, you should already be able to read newspapers in your native tongue. At that point, reading a newspaper in a foreign tongue is simply a matter of vocabulary.

True there are different uses of language, and styles of writing. And newspapers do have style which differs from other kinds of writing. But you just read, and read and figure them out.

The problem with most learners, however, is that they aren’t reading novels and short stories. Most learners need to just accept that they need practice. They need to read, and read, and stumble, and fall, and read again, until they get it.

I didn’t develop a taste for reading the newspaper in English untill I was in my late twenties. But, by that time I had read countless books in English, and completed 16 years of education. I only began reading newspapers because I had to read foreign newspapers at college. Then I learned to read the newspapers in English first, to help me understand the foreign newspaper.

One of the problems, specifically with Khmer learners is that there is so little written material available in Khmer. American students have had exposure to newspapers, magazines, novels, reference books, poetry, plays, encyclopedias, diaries, biographies, textbooks, comic books… Most Khmers haven’t had this exposure.

If they haven’t read it in their native tongue, how could they read it in a foreign language?

And, I am not just picking on Khmers. True these styles of writing are not available in Khmer language, but even in Chinese, Korean, or Vietnamese education, where these many styles of writing exist, students may not have had exposure to them. For example, Taiwanese college students said that during 12 years of primary school they never wrote a single research paper.

But then they were asked to do that in English, in their ESL classes.

Currently, I have a Thai friend, named Em, who is studying in USA. He has been there for three years, studying English full time, and still can’t score high enough on his TOEFL exam to enter an American community college. In Thailand he is a college graduate, but education in Thailand is way behind western education. And in the developed world, American community colleges are about the single easiest schools of higher learning to enter.

If Em finally passes the TOEFL and gets into community college, in the first two years of core requirements for an American Bachelor’s Degree, he will be given assignments such as “Read George Orwell’s 1984, and explain how it is an allegory for communism, and how it applies to the Homeland Security Act in the US.”

When foreign students stumble on an assignment like this, they always blame their English level. But I am confident that the average graduate from most Asian countries couldn’t do this assignment in his native tongue. Their curriculum just doesn’t include these types of analytical book reports.

When I was teaching in Korea, there was a famous story circulating around the sober ESL community. A Korean girl, from a wealthy family, had won a national English contest. She had been tutored by an expensive home teacher, almost since birth, and her English level was exceptional. The prize was a scholarship to a prestigious boarding school in the Unites States, graduation from which almost guaranteed admission to an Ivy League school.

Apparently, one of the first assignments she was given at her new school in America was to read a poem and write an original analysis of it, and then give a presentation in class. When it came time for her presentation, the student stood up and dutifully recited the poem, word for word, she also regurgitated, exactly, what the lecturer had said about the poem in class. And she failed.

In Korea, her incredible memory and ability to accurately repeat what the teacher had said, had kept her at the top of her class. But in America, she was being asked to do much more than that; think, and analyze, create, present, and defend.

The majority of learners believe that their difficulty in dealing with foreign education, books, newspapers, or conversations lies in their lack of vocabulary or failings of language. But once they posses a relatively large vocabulary, the real problem is some combination of culture and practice.

Getting back to the Khmer student and his problem reading English newspapers: To understand English newspapers you also have to know all of the news and concepts in the newspaper. The best way to deal with foreign newspapers, at the beginning, is to first read a news story in your own language. Then read the same news story in the foreign language newspaper. Also you can watch the news in your own language and then in whatever language you are studying, and compare.

Translation isn’t just about knowing words. You have to know concepts. The first rule of translation is that the written text must convey the same meaning in the target language as it did in the source language. Even if the wording, in the end, is not even remotely like the original. No matter how good your foreign language skills are, you cannot convey meaning which you don’t know in your native tongue.

Recently, newspapers in Asia were running stories about the Taiwan Y2K crisis.

To understand the newspaper stories, you would first need to understand the original, global Y2K crisis. The global Y2K issue was something that Cambodia wasn’t very involved in because there were so few computers in Cambodia in the year 1999. There were probably less than one hundred or so internet connections in Cambodia at that time. Next, you would have to know and understand that Taiwan has its own calendar, based on the founding of the Republic of China in 1911. Government offices and banks in Taiwan record events according to the Republic of China calendar, which means if you take money out of an ATM machine today, the year will show as 99.

Once you know and understand these facts, then you would know that Taiwan is about to reach its first century, in the year 2011, and is facing a mini-Y2K crisis, because the year portion of the date in the computer only has two digits.

The bulk of my readers do not live in Asia, and may not have known anything about the history of Taiwan, or the Taiwan date. But, any person with a normal reading level should have understood my explanation. It is not necessarily a requirement that you posses prior knowledge of the exact situation you are reading about, but you can relate it to other things you know about, for example, other calendars and otherY2K problems.

If you look at the above explanation, the vocabulary is fairly simple. There are probably only a small handful of words, perhaps five or six, which an intermediate language learner wouldn’t know. So, those words could be looked up in a dictionary. And for a European student, with a broad base of education and experience, that would be all of the help he would need. But for students coming from the education systems of Asia, particularly form Cambodia which is just now participating in global events such as the Olympic Games for the first time, it would be difficult, even impossible, to understand this or similar newspaper stories.

The key lies in general education, not English lessons. Students need to read constantly and simply build their general education, in their own language first, then in English, or else they will never understand English newspapers or TV shows.

]]>Antonio Graceffo is an applied linguist, and martial arts and adventure author living in Asia (check out our interview with him here). His books, including ”The Monk from Brooklyn”, are available at Amazon.com.

Googling around the internet I found a lot of sites where people had written in saying, “I am studying language XYZ, and I want to know how many words I have to know to be able to read a newspaper.”

Googling around the internet I found a lot of sites where people had written in saying, “I am studying language XYZ, and I want to know how many words I have to know to be able to read a newspaper.”

This question is particularly relevant for people who are studying Chinese, where each word is a character, and most students know the exact number of characters that they can read. Whereas students who have been studying Spanish, German, or Vietnamese for a period of years, wouldn’t generally know the exact number, or may not even know an approximate number of words that they understand.

This information is relevant for anyone studying a foreign language, including English, particularly if your goal is to study at a university overseas or to work in a professional job in the foreign language environment.

Checking a number of websites, the answers varied substantially.

On aksville.com, someone took the time to write a long reply, explaining that major newspapers, such as USA Today, are written at a 6th to 8th grade level and require approximately 3,000 words to read.

Another site, called blogonebytes.com: “I read somewhere that to be able to carry on a good conversation in “Mandarin Chinese” one should know about 3,000 characters, and about 7,000 characters to read technical books.”

A follow up comment by a reader on the same site said, “You will need to know a minimum of 3000 characters to be proficient. You will need to be able to speak and understand in the range of 5000-7000 characters.”

According to Omniglot, a site which I tend to have a lot of respect for, “The largest Chinese dictionaries include about 56,000 characters, but most of them are archaic, obscure or rare variant forms. Knowledge of about 3,000 characters enables you to read about 99% of the characters used in Chinese newspapers and magazines. To read Chinese literature, technical writings or Classical Chinese though, you need to be familiar with at least 6,000 characters.”

I had always heard that the range was somewhere between 1,500 and 3,000 words to read a newspaper. In the case of Chinese, I know that I can read right about 3,000 characters, and yet, I absolutely cannot read a newspaper. If you hand me a newspaper, I can pick out words that I know, but I can’t actually read and understand the stories.

In Bangkok, I have several friends who are extremely conversant in Thai, and they can read a menu. But they would need an entire day and a dictionary to read a single newspaper story. And even then, they wouldn’t understand everything.

With German, after four years of studying and working as a translator and researcher in the country, I can obviously read anything. But, I have no idea how many words I know. Now that I am embarking on my study of Bahasa Malay, and also making plans to go back and finish learning Vietnamese, I am becoming very curious how long it will take to get my reading level anywhere close to what it is in English or Spanish. My own experience with Chinese made me question this 3,000 word figure. Also, as a person who earns most of his living from writing for magazines, newspapers, and books, I would hate to believe that I only write a 3,000 word vocabulary , and on a 6th to 8th grade level.

As many times as I attended 9th grade, you would think I would be writing at least at high school level.

The two facts that I wanted to verify were, the average reading level of The New York Times, my hometown paper, and the average number of words per edition.

The first question was easy to answer.

The May 2, 2005 edition of “Plain Language At Work Newsletter”, Published by Impact Information Plain-Language Services, explained that there are two generally accepted scales for determining the reading level of various publications. They are the Rudolph Flesch Magazine Chart (1949) and the Robert Gunning Magazine Chart (1952). Both charts analyzed such aspects of a magazine or newspaper such as, average sentence length in words and number of syllables per 100 words. Based on this information, they assigned a school grade reading-level to the publication. According to this rating system, The Times of India was considered the most difficult newspaper in the world, with a reading level of 15th grade. The London Times scored a 12th grade reading level, as did the LA Times and the Boston Globe. The survey must have been flawed, however, because they assigned The New York Times a reading level of 10th grade, which is lower than the LA Times, when everyone knows quite well that New York is better than California or any other place which is not New York.

If you get most of your news from Time Magazine, you might be pleased to know that Time and TV Guide both scored a 9th grade reading level.

The survey didn’t cover newspapers written in languages other than English, but if we assume that we are shooting for an average 10th grade level, this will probably be close to what you need to read a newspaper in any language.

The next question was much harder to answer. How many words do I need to read the New York Times? I have never believed the low estimates of 3,000 or less, simply because every event that happens anywhere in the world, any human situation can appear in the Times as a news story and could of course, require the appropriate vocabulary.

To answer the question, I went to the June 4, 2010 New York Times online and I chose 8 articles, taken from several different sections, because I assumed they would all require different vocabulary. The stories were: “Pelicans, Back From Brink of Extinction, Face Oil Threat”, “BP Funneling Some of Leak to the Surface”, “John Wooden, Who Built Incomparable Dynasty at U.C.L.A., Dies at 99”, “An Appraisal : Wooden as a Teacher: The First Lesson Was Shoelaces”, “Should you be able to discharge student loans into bankruptcy?”, “On the Road to Rock, Fueled by Excess” as well as other tidbits, announcements and follow up articles.

In some cases, if the articles were very long, I didn’t take them in their entirety, assuming there would be much repetition of words.

In all, I took parts of about 8 stories, comprising 51 pages of text. The stories I took didn’t even represent 10% of the total content of this particular edition of The New York Time, June 4, 2010 online edition.

I pasted the words into a word document, converted them to a single column table, which ran over 450 pages long. Then I sorted the table alphabetically. Up to this point, it was easy, just pressing buttons. Next, I had to go through all 450 pages, all 10s of thousands of words, removing duplicates. It was one of the most tedious exercises I have ever conducted in my life. It was exactly the type of obsessive compulsive behavior that gets people locked up in mental institutions. It took 16 hours. By the 10th hour, I began hallucinating. Nearing the 12th hour, I believed I was a hummingbird of some kind.

I allowed plural forms of nouns, so I counted “car” once and “cars” once. I also included all forms of a verb, so “walk” once, “walked” once, and “walking” once. I counted proper nouns, including place names, as the names of people and countries will come up in the news and you need to know them. Also, in foreign language, particularly Asian languages, the grammatical forms and proper names may not even be recognizable if you haven’t studied and learned them.

When I was finished, I found that the random sampling of stories I chose contained 4,139 unique words. This was much higher than the estimates I had read on some websites, but was well in line with what I suspected. If I had the energy to complete a similar analysis of the entire edition, I would have to believe the number would increase. And if we monitored the newspaper over a period of one month, analyzing the text every day, and comparing the vocabulary against an accumulated list, I would imagine that it would grow. Most likely the difference in vocabulary from day to day would be small, but still, the necessary vocabulary would increase.

Comparing the dialogues in my Chinese textbooks with the vocabulary that appeared in these New York Times articles, much of what I learned in school was useless. For example, all foreign language textbooks have chapters devoted to shopping at the market, where you have to memorize tedious lists of Fruits and vegetables. In these Times articles, not a single fruit name was mentioned. Neither my Vietnamese, Chinese, or Bahasa textbooks include the names of heads of state of various countries. But obviously, these names came up in world news stories.

Below is a small sampling of words that I found in the news story which, I don’t know how to say in Chinese. Some of these words, I question, however, if the average 9th grader would know them. Do 9th graders know: abetted, absinthe, archeo-feminist, or bearish?

abetted albeit assesses bankruptcy biofuels able-bodied. Amandine assessment batch biography abortions ambivalent assets bawdy-sweet black-clad absinthe anachronistic asthmatic bearish bleak absurd. anarchic audience-pleasing Bedford blemish accord Appended aura befriended blockade across-the-board Archbishop autobiography behind-the-back blowout activists archeo-feminist autograph-seekers benefits bond Advocates articulate awfully best-selling booster aerodynamic assertion babbles bioenergy breakthrough

Names and proper nouns are important for understanding news stories. In language textbooks you may learn the names of major countries and the capital cities, but news happens in small cities and even villages as well. To read the news you need to know the names of political parties, famous people, economic theories, financial indices, global corporations, educational institutions, associations, and international organizations such as the UN.

All of these names were taken from the same collection of stories. Do you know how to say these in Vietnamese or write them in Thai?

Cypriot Delta Geneva Mediterranean Bihar Baltic Democrat Greece Nehru Turkish-controlled Brooklyn Denmark Uttar Metropolitan Nasdaq Iranian Dow Midwesterner Mayor Polytechnique Louisiana Durbin Scotch Reich Iskenderun. pro-Greek Dutch-Irish Rev. Latino Kentucky. California Baptist BENJAMIN Bonaventure/Agence Burke/Associated Cambridge Chicago-based Berkeley Pennsylvania. Bush Cyprus Barataria-Terrebonne Navy BP Dallas-Fort Audubon Gandhi. Bess Dalit Arce

How many of the above terms were you able to translate or transliterate into the language that you study? This is the level of reading that an adult native-speaker can do, and this should be your goal. If the task doesn’t seem daunting enough, remember, in this article, we were only concerned with vocabulary. But you could have a vocabulary of a million words not be able to understand a newspaper or a book. For real communication, you need a comprehensive approach to language, which includes culture, syntax, context, and grammar.

It’s a long stretch. I know. And it can seem impossible. But remember, every Sunday in New York City Catholic mass is said in 29 languages. For more than a century, large numbers of immigrants, my family included, have been coming to America and Canada in search of a better life. Most of them learned English with less than half of the education of the average person reading this article.

So, if your Grandma and Grandpa could learn a new language to a level of functionality, so can you.

Like Antonio’s writing?

Check out some of his fantastic books on travel, martial arts, language learning and endangered cultures.

]]>

Enjoy!

____

]]>He has done a great job of distilling down the most important factors in learning a foreign language quickly and effectively, adding lots of humor and wit in typical Stever style. His programs are especially good for you English learners out there as they are interesting, short, and include transcripts of the shows.

I am honored to be featured in the show; I hope you enjoy it.

Listen to the episode on The Get-it-done Guy site or download it in iTunes.

]]> OK. Everyone knows that quote by Woody Allen or whoever about showing up. You know, “70% of winning is showing up”. Well, Woody Allen, that daughter-dating scoundrel, lied to you. The truth is “70% of winning is showing up” is a bunch of bull…

OK. Everyone knows that quote by Woody Allen or whoever about showing up. You know, “70% of winning is showing up”. Well, Woody Allen, that daughter-dating scoundrel, lied to you. The truth is “70% of winning is showing up” is a bunch of bull…

…Because, in fact, 100% OF WINNING IS SHOWING UP. I mean it. That’s all you have to do. Show up. Be there. And it will take care of itself. Have you ever noticed that people at the top of their respective fields are often the most prolific? Do you think this is an accident? Chief, this is not a coincidence. Sure, there are exceptions. But take TEDZUKA Osamu/手塚治虫, one of the most prolific manga creators in history. Ask yourself, was he prolific because he was good or good because he was prolific? I say the latter. Shakespeare wrote quite a bit of noss, too. Michael Jordan and Larry Bird practiced like absolute fiends — we shouldn’t insult them by attributing their skill to race, height (MJ was below NBA average, by the way) or even talent until we’ve spent at least as much productive court time as them. Let me put it this way — assuming you are able-bodied, if you worked as hard as an NBA player for as long as an NBA player on basketball, you would be an NBA player, but only if you worked as hard. That Pavlina chap has like a kajillion articles on his blog: he didn’t make it off one post. More on topic, the best group of Japanese speakers on the planet, a group many call “the Japanese”, just happen to spend more time hearing and reading Japanese than any other group. They’ve “shown up” to Japanese as if it were their…job or national pastime or something. But there’s nothing special about this group of people; when a Japanese person speaks Japanese to you, what she is demonstrating is nothing more than the result of dedication, albeit often unwitting dedication. Whether you are Japanese by default (born and raised in Japan) or by choice, it doesn’t matter, your path and your task are essentially the same: show up.

I’m from Kenya. Sure, we have a snow-capped mountain, but we don’t have real snow or ice or anything. Yet I learned to ice-skate last year. Do I have some talent for ice-skating? No. But I read up on Wayne Gretzky and how he had ice-skated every day (4-5 hours a day), how his dad had made him a home rink and everything. Apparently, he even had his skates on while eating dinner (he’d wolf down that Canadian food they fed him, and then he’d go back outside; he skated for hours every day, and went pro at about 17). I’m not an ice-hockey expert, but it seems quite clear to me that Gretzky made himself a great hockey player purely through ice time; that man showed up on ice for more hours than any of his peers. So I tried to model the man in my own small way, and ice-skated almost every day (4 days/week minimum, 2 hours per day — sometimes 3 hours, sometimes 90 minutes) for two straight months (November and December). Now I can ice-skate. It wasn’t magic. The combination of being on the ice all the time and the people who saw me on the ice all the time and decided to give me some pointers, and this burning desire to not be out-skated by 6-year-olds (freaking toddlers giving me lip and having the skill to get away with it…over my dead body, man, over-my-dead-body), all that combined to make me a competent skater. No one who sees me knows it’s been less than a year since I actually learned to skate. I can barely even remember what it was like when I used to walk around that rink holding onto the wall for dear life. (For the record, the first time I touched the ice was in August 2002 at a mall in Houston, Texas. The second time was in December 2002 in Salt Lake City, Utah. In both cases, I didn’t actually know how to skate, and nothing carried over to my ice-skating project that started in November 2006). Anyway, the point is, after being on the rink all that time on a daily basis, Greztky or no Gretzky, it would be hard not to learn how to skate. When you show up, it’s hard not to succeed. With all the time I spent hardcoring on Japanese, it would be a struggle not to be fluent.

Today, all over Japan, Greater China and the world, kids are being born. OK, admittedly not that many kids (haha…gotta love that population shrinkage humor! *wink* *nudge*), but they are being born. Those kids are going to know Japanese/Mandarin/Cantonese. But not because of parenting or genetics as such, but because they’re going to show up. They’re going to be surrounded by Japanese/Chinese 24/7/365.24219878. Are you going to let them beat you? Babies? Freaking BABIES? Beat YOU? Are you going to take that? You, a human being with a marvellous working brain capable of learning whatever is given it? And you’re going to let babbling, drooling half-wits (sorry, babies…don’t take it personally) beat you? If not, then get up off your rear and start doing all [language] all the time!

I’m going to take a leap here and tell you what I really think: I don’t believe in prodigies. I do not believe that any person holds a significant advantage over you; I do not deny the possibility that some people may have an advantage over you, but I absolutely reject the idea that that advantage is significant. I explained this in “You can have do or be ANYthing, but you can’t have do or be EVERYthing”. I think people invented the idea of prodigies in order to excuse themselves and their own children while seeming to congratulate the receiver of the title “prodigy”. It’s much easier on everyone’s egos to say “I or my child cannot do thing T like person P because person P has some semi-magical genetic superpower” than to say “I or my child cannot yet do T like P because I have not yet worked as hard W as P”. This is why Buddhism, which started off as a personal development movement, metamorphosed into a religion. Why be like Mike or Siddharta, when you can just sit back and worship them? Why work on your jumps, when you can watch the fruits of Michael’s work on his? Why free your own mind, when you can look up to someone who’s already freed his? It’s a very aristocratic idea that has no place in a true meritocracy, but the very people who are screwed over by it (regular folk like us) are at the same time very much in love with it: If there are prodigies, no one will call us out for not trying because they’re not trying either, and because we have created a condition that can only be fulfilled by accident of birth, our excuse is airtight: we can go about being mediocre for the rest of our lives, blameless.

Gretzky, Jordan, these people worked harder at their sports than you and I. So they started working earlier than you, this doesn’t make them prodigies, child or otherwise, this just makes them people who started earlier (and not even that early, Jordan famously got cut from his HS basketball team). To admit that they were not prodigies, to admit that they busted their little behinds to get where they were (no matter their age), does not make them less. To me, it only makes them more; it makes them greater. These were not superhumans. These were normal humans who made themselves super; they were not given a legacy like a Betty Crocker cookie mix that just needed eggs and milk, they made one from scratch. And that, to me, is something (someone) infinitely greater.

Bruce Lee is reported to have said:

“I fear not the man who has practiced 10,000 kicks once, but I fear the man who has practiced one kick 10,000 times.”

A lot of times, we judge people (including ourselves), we call them (ourselves) “normal”, “prodigy” or “challenged” based on their first try. On their FREAKING first try. Don’t EVER EVER EVER EVER EVER EVER judge yourself on your first try. At least wait until your 10,000th.

Don’t buy into all this kafuffin about how you have to start golf or violin or a language in the womb if you ever hope to be good. The only real reasons that there aren’t many late bloomers are money and flexibility. Money to buy equipment and time to practice, and flexibility of the mind — a willingness to learn and grow, to accept change and, yes, even to accept sucking for a while.

Adults have this competence fetish; they cling desperately to their dignity like a little boy to his security blanket; they want to be good at everything they do, and (they think) everyone expects them to be good at anything they do if they are to do it at all — adults are meant to be dignified and able; adults aren’t allowed to show ignorance or confusion. Well, forget that crap. Let go of your pride: you will suck at anything you are new at and little kids will be better than you. It’s okay, that’s how it’s supposed to be — those kids used to suck, too. Sucking is always the first step on the path to greatness; it’s not a question of how many times the earth has made a full rotation around the sun since you were born; it’s a question of what you’ve done during those rotations. As my gamer friends might say — all who pwn must first be pwned. And the time to be pwned is at the beginning. You are a noob, accept it; it’s not a death sentence, it’s just a rank — you can win yourself a promotion.

The fact is, you are a human. Compared to other animals, you can’t run very fast, you can’t jump very high, you aren’t very big or strong. But you have this thing called a brain. And it’s purpose is to learn to do things — new things, things that it didn’t know before. This brain is, of course, connected to the rest of your body so your whole body can join in the fun of learning new things; your body itself is constantly growing and changing. You’re not like a statue, motionless and set in stone, unless you choose to be. You’re not “too old”, it’s not “too late” — who even gave you the right to decide what time was right? I never got that memo! Who died and made you the god of When It Is No Longer The Right Time To Do Something?! Are you going to let your life be ruled by stupid old wives’ tales and stale folk wisdom? Are you going to fit yourself to bad research results? Are you going to be guided by how things are usually done? Are you going to be a little worker ant and live inside that cruddy little box of mediocrity that the world would draw for you if you would let it? Are you going to just read history or are you going to make it? Are you going to spend your whole life Monday-morning-quarterbacking yourself, talking about what you would do if you were younger? Are you going to live out your own little Greek tragedy, fulfilling everyone else’s lowest expectations of you? I think you know the answers to those questions. So, stop whining, and start doing. Whatever it is. Do it. And keep doing it. As long as you keep moving, you’re always getting closer to your destination.

Nap Hill said it best:

“Do not wait; the time will never be “just right.” Start where you stand, and work with whatever tools you may have at your command, and better tools will be found as you go along.”

This article is copyright (©) 2007 Khatzumoto/AJATT.com and reprinted with permission | May 18, 2010

]]>