Antonio is an applied linguist, and martial arts and adventure author living in Asia (check out our interview with him here). His books, including ”The Monk from Brooklyn”, are available at Amazon.com.

When I started my Vietnamese intensive course, a lot of non-linguistists I talked to said that the Chinese students would have an advantage because they already speak a tonal language.

It is true that some Westerners could be completely stumped by tones, and just not get the language at all. But, a person who already speaks a tonal language does not have an advantage over a Westerner or a Korean or Japanese who is intelligent, motivated and who is trying to learn tones. Remember that a Cantonese or Mandarin speaker has mastered the tones of his or herlanguage, not the tones of Vietnamese. Saying that someone from a tonal language would have an advantage is like saying people from languages with words, or sounds, or verbs or adjectives would have an advantage.

Mastery of a particular language is based EXCLUSIVELY on your mastery of THAT language, not other languages. If you know tones in one language, you still need to learn the specific tones for the new language you are studying.

Next, people who were more language-savvy suggested that both the Chinese and Korean students would have a huge advantage because of all of the Chinese cognates between Chinese, Korean and Vietnamese. But in my class, I have noticed the Chinese and Koreans don’t even hear or notice the cognates. I help Schwe Son translate his homework every single day and he never sees the cognates. The Koreans are the same.

In addition to not having a particular advantage, our Chinese classmate, Schwe Son (not his real name) seems to have a number of special problems because of his Chinese mother tongue. For example, we learned the words for “half a million.” But in Chinese, there is no word for a million. They count by ten-thousands. So, a million is 100-ten-thousands. Schwe Son pointed at the Vietnamese words for half a million, nửa triệu, and asked me to translate. I translated it into Chinese, literally, “Half of 100-ten-thousands.” The look on Schwe Son’s face was as if he had just seen me defecate in a frying pan. “Why don’t they just say 50-ten-thousands?” He asked. He had a point.

The old Vietnamese word for Burma is ‘Miến Điện’ the same as in Chinese. But now the Vietnamese have created a Vietnamese spelling for the countries new name of Myanmar. Most languages and most countries move toward not changing country or city names, but just spelling them in their own language. This is why Beijing is now Beijing in English, instead of Peking. But Chinese cannot move in that direction, as it is impossible to spell foreign words with Chinese characters. As a result, many Chinese place names are outdated. Or, they have to create a totally new word, which may or may not be recognizable as the place it relates to.

So, in class, when we encounter country names that are instantly recognizable for Western or Korean students, but for which Schwe Son needs a translation. Afterwards, the translation has no real meaning for him. He just has to memorize it, although it doesn’t relate to anything.

We have only had eight days of class so far, but have already encountered a lot of Chinese cognates. The word for ‘a shop’ which I learned in Hanoi was ‘cửa hàng’. But here in Saigon they say ‘tiệm.’ this is a cognate from the Chinese, ‘Diàn’. And yet, when we came to this word, Schwe Son asked me to translate. I said, in Chinese, “tiệm means Diàn.” Schwe Son simply said, “OK.” And immediately wrote the Chinese character in his notebook. There was not even a flicker of recognition.

Here is a list of Chinese cognates from the first eight days of class (I have only listed modern Mandarim cognates. If I were to list ancient Chinese cognates (similar to Korean and Cantonese cognates) the list would be much, much longer.)

| English | Vietnamese | Chinese Pronunciation | Chinese Character |

| Please | xin | Qǐng | 請 |

| Shop (n) | tiệm | Diàn | 店 |

| South | nam | Nán | 南 |

| East | đông | Dōng | 東 |

| come | đi lại | Lái | 來 |

| Zero/Empty | Không (zero) | Kōng (empty) | 空 |

| zero | linh | Líng | 零 |

| prepare | Zhǔnbèi | chuẩn bị | 準備 |

| money | tiền | Qián | 錢 |

| side | bên | biān | 邊 |

| Café | quán cà phê | Kāfēi guǎn | 咖啡館 |

| wrap | bao | Bāo | 包 |

| pronunciation | phát âm | Fāyīn | 發音 |

| dictionary | tự điển | Zìdiǎn | 字典 |

| Burma | Miến Điện | Miǎndiàn | 緬甸 |

| Country | Quốc gia | Guójiā | 國家 |

| Germany | Đức | Déguó | 德國 |

Vietnamese is a Mon-Khmer language, in spite of having so many Chinese cognates. Chinese is a single syllable language, with a lot of compound words. But Mon Khmer languages have multi-sylabic words. The Chinese student is having a lot of difficulty with the pronunciation of multi-sylabic words.

Possession in Khmer, Vietnamese, and English can me made, using the verb, “to belong to”, as in, ‘the book belongs to me.’ But most languages don’t have that construction. Neither Korean nor Chinese has it. (It exists in Korean, but no one uses it). So, they were all having a hard time understanding the concept of, “book belongs to me”, “sách của tôi”. The Chinese student kept pushing me for word-for-word translations. But obviously, there was no way to translate this word-for-word. I could only translate the meaning. In Chinese, “This is my book.” But then he would flip the book to the previous day’s lesson. “I thought this phrase meant ‘this book is mine’.” He said. “Yes,” I said. “The meaning is the same, but the wording is different.” “OK, so what is it in Chinese?” he asked again.

Schwe Son realizes he needs to improve his English in order to get through his study of Vietnamese language. So, every day, in addition to translating his homework into Chinese, he asks me to translate it into English for him. And this creates a whole other set of problems.

In Vietnamese there is a word for the noun, “a question” (câu hỏi), and the verb “to ask” (hỏi) is a related word. The noun, “answer” (câu trả lời) is also related to the verb “to answer” (trả lời). But in English, obviously, the verb “to ask” is unrelated to the noun “a question.”

“Open and close your book” in Vietnamese is exactly as it is in English. Meaning the same words “open and close” could be used for the door or a drawer or a crematorium. But in Chinese, the words for “open and close your book” are unrelated to “open and close the door.” I translated for him, and he understood what the phrase ‘open your book meant’ in Chinese, but it was a completely unrelated phrase, that had no meaning and no connection to anything else for him. For the rest of the classmates, once they learned ‘open and close’ they could apply it to anything. But for Schwe Son it was one isolated piece of linguistic noise.

There are so many aspects to learning a language: vocabulary, grammar, pronunciation, usage, and many more. Though an argument could be made that a student with a given native tongue may have an advantage in one area, he or she may have other areas with particular difficulties.

]]>Antonio Graceffo is an applied linguist and martial arts and adventure author living in Asia (check out our interview with him here). His books, including ”The Monk from Brooklyn”, are available at Amazon.com.

A Khmer student wrote to me on youtube and asked me to produce videos about how to read English language newspapers.

A Khmer student wrote to me on youtube and asked me to produce videos about how to read English language newspapers.

“I’d like to ask you to make videos how to read newspaper and translate it from English to Khmer. I Khmer and I having a problem to understand English phrases.” Wrote the student.

Language learners often write telling me about some area of learning or area of their lives where they are experiencing difficulties of comprehension and ask me for a trick or a guide to help them learn.

As I have said in numerous other language learning articles, there are no tricks and no hints. The more hours you invest, the better you will get. And if your goal is to read at a native speaker level, then you need to read things a native speaker reads. If you are a 22 year-old university graduate, then you need to be reading at that level in the foreign language. And you won’t get there by reading textbooks ABOUT the language. You will get there by reading books, articles, and textbooks IN rather than ABOUT the language.

If we analyze this latest email, the student says he has trouble reading, and he specifically singled out newspapers.

Obviously, reading is reading. On some level, reading a newspaper is no different than reading a novel or reading a short story.

If you are reading novels and short stories, you should be able to read newspapers. If I asked this student, however, he is probably is not reading one novel per month in English. If he were, newspaper reading would just come.

Therefore, the problem is not the reading or the newspapers, per se. The problem is the lack of practice.

I never took a course called “Newspaper Reading” in English. I just started reading newspapers. And at first, I had to learn to deal with the language, structure and organization of newspaper writing, but no one taught me, or you. It just came to us. The same was true for German or Spanish newspapers which I can read almost as well as English. No one taught me, or taught Gunther or Pablo, it just came through practice.

A point, that I have made many times in articles, is that when you begin learning a foreign language, you are not an idiot. You are not starting with an empty brain. One reason it takes babies three years to learn their native tongue is because they are also learning what a language is and how language works. You know all of that, and much more. Babies don’t know that there is such a thing as grammar. Every single piece of vocabulary has to be learned. A seven year old may not know the words “population, economy, government, referendum, currency” in his native tongue. So, reading a foreign newspaper would be difficult for him, because reading a newspaper in his mother tongue is difficult for him.

If you are an adult, coming from a developed country, with at least a high school or university level of education, you should already be able to read newspapers in your native tongue. At that point, reading a newspaper in a foreign tongue is simply a matter of vocabulary.

True there are different uses of language, and styles of writing. And newspapers do have style which differs from other kinds of writing. But you just read, and read and figure them out.

The problem with most learners, however, is that they aren’t reading novels and short stories. Most learners need to just accept that they need practice. They need to read, and read, and stumble, and fall, and read again, until they get it.

I didn’t develop a taste for reading the newspaper in English untill I was in my late twenties. But, by that time I had read countless books in English, and completed 16 years of education. I only began reading newspapers because I had to read foreign newspapers at college. Then I learned to read the newspapers in English first, to help me understand the foreign newspaper.

One of the problems, specifically with Khmer learners is that there is so little written material available in Khmer. American students have had exposure to newspapers, magazines, novels, reference books, poetry, plays, encyclopedias, diaries, biographies, textbooks, comic books… Most Khmers haven’t had this exposure.

If they haven’t read it in their native tongue, how could they read it in a foreign language?

And, I am not just picking on Khmers. True these styles of writing are not available in Khmer language, but even in Chinese, Korean, or Vietnamese education, where these many styles of writing exist, students may not have had exposure to them. For example, Taiwanese college students said that during 12 years of primary school they never wrote a single research paper.

But then they were asked to do that in English, in their ESL classes.

Currently, I have a Thai friend, named Em, who is studying in USA. He has been there for three years, studying English full time, and still can’t score high enough on his TOEFL exam to enter an American community college. In Thailand he is a college graduate, but education in Thailand is way behind western education. And in the developed world, American community colleges are about the single easiest schools of higher learning to enter.

If Em finally passes the TOEFL and gets into community college, in the first two years of core requirements for an American Bachelor’s Degree, he will be given assignments such as “Read George Orwell’s 1984, and explain how it is an allegory for communism, and how it applies to the Homeland Security Act in the US.”

When foreign students stumble on an assignment like this, they always blame their English level. But I am confident that the average graduate from most Asian countries couldn’t do this assignment in his native tongue. Their curriculum just doesn’t include these types of analytical book reports.

When I was teaching in Korea, there was a famous story circulating around the sober ESL community. A Korean girl, from a wealthy family, had won a national English contest. She had been tutored by an expensive home teacher, almost since birth, and her English level was exceptional. The prize was a scholarship to a prestigious boarding school in the Unites States, graduation from which almost guaranteed admission to an Ivy League school.

Apparently, one of the first assignments she was given at her new school in America was to read a poem and write an original analysis of it, and then give a presentation in class. When it came time for her presentation, the student stood up and dutifully recited the poem, word for word, she also regurgitated, exactly, what the lecturer had said about the poem in class. And she failed.

In Korea, her incredible memory and ability to accurately repeat what the teacher had said, had kept her at the top of her class. But in America, she was being asked to do much more than that; think, and analyze, create, present, and defend.

The majority of learners believe that their difficulty in dealing with foreign education, books, newspapers, or conversations lies in their lack of vocabulary or failings of language. But once they posses a relatively large vocabulary, the real problem is some combination of culture and practice.

Getting back to the Khmer student and his problem reading English newspapers: To understand English newspapers you also have to know all of the news and concepts in the newspaper. The best way to deal with foreign newspapers, at the beginning, is to first read a news story in your own language. Then read the same news story in the foreign language newspaper. Also you can watch the news in your own language and then in whatever language you are studying, and compare.

Translation isn’t just about knowing words. You have to know concepts. The first rule of translation is that the written text must convey the same meaning in the target language as it did in the source language. Even if the wording, in the end, is not even remotely like the original. No matter how good your foreign language skills are, you cannot convey meaning which you don’t know in your native tongue.

Recently, newspapers in Asia were running stories about the Taiwan Y2K crisis.

To understand the newspaper stories, you would first need to understand the original, global Y2K crisis. The global Y2K issue was something that Cambodia wasn’t very involved in because there were so few computers in Cambodia in the year 1999. There were probably less than one hundred or so internet connections in Cambodia at that time. Next, you would have to know and understand that Taiwan has its own calendar, based on the founding of the Republic of China in 1911. Government offices and banks in Taiwan record events according to the Republic of China calendar, which means if you take money out of an ATM machine today, the year will show as 99.

Once you know and understand these facts, then you would know that Taiwan is about to reach its first century, in the year 2011, and is facing a mini-Y2K crisis, because the year portion of the date in the computer only has two digits.

The bulk of my readers do not live in Asia, and may not have known anything about the history of Taiwan, or the Taiwan date. But, any person with a normal reading level should have understood my explanation. It is not necessarily a requirement that you posses prior knowledge of the exact situation you are reading about, but you can relate it to other things you know about, for example, other calendars and otherY2K problems.

If you look at the above explanation, the vocabulary is fairly simple. There are probably only a small handful of words, perhaps five or six, which an intermediate language learner wouldn’t know. So, those words could be looked up in a dictionary. And for a European student, with a broad base of education and experience, that would be all of the help he would need. But for students coming from the education systems of Asia, particularly form Cambodia which is just now participating in global events such as the Olympic Games for the first time, it would be difficult, even impossible, to understand this or similar newspaper stories.

The key lies in general education, not English lessons. Students need to read constantly and simply build their general education, in their own language first, then in English, or else they will never understand English newspapers or TV shows.

]]>

A quick search in the Android Marketplace or Apple App store reveals pages and pages of Chinese dictionaries, including free, ad supported versions, as well as paid apps between $1 and $20 USD. After sampling a number of them, I have settled in on two favorites that seem to be the easiest to use, have the most features, and offer both free and pro versions:

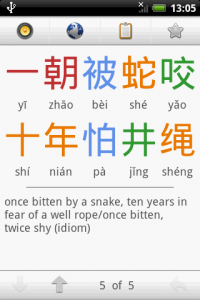

Best Chinese Dictionary App on Android

So far, my favorite Chinese dictionary for Android is Hanping Ch-En. There is a free version and a paid version for £4.99 (about $7.75 USD).

Here is a list of the features I like best (as available on version 2.2.6 Pro):

Traditional and simplified Chinese characters.

Traditional and simplified Chinese characters.- Search by Chinese characters, Hanyu Pinyin, English terms (install the free “HanWriting IME” app so you can actually write characters by hand like on an iPod Touch, iPhone or iPad).

- Search for characters in the beginning, middle or end of a term (click the little wrench icon to right of the search field to change this setting.)

- Pinyin is shown right below each character on the detail page.

- Chinese count words are shown when appropriate (e.g. 個, 雙, 台, etc.)

- Drill down on individual characters within multiple character words.

- Audio versions of Chinese terms.

- Shortcut to more details, sample sentences, Google dictionary and Wiktionary via the Android browser.

- Shortcut to “save to clipboard” so you can paste into emails, text messages, other dictionaries, etc.

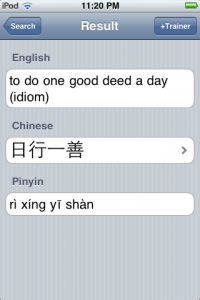

Best Chinese Dictionary App on iOS4

My favorite app for iPod Touches, iPhones and iPads is KTdict C-E. There is a free version and a pro version for $3.99.

Here are the top features as I see it (as available on version 1.6.1 Pro):

Beautiful UI (user interface) as one would expect on an Apple device.

Beautiful UI (user interface) as one would expect on an Apple device.- Traditional and simplified Chinese characters.

- Search by Chinese characters (which is a breeze with Apple’s handwriting input), Hanyu Pinyin, and English.

- Drill down on individual characters within multiple character words. Each character can then be copied to the clip board, looked up in the dictionary by itself, or searched within Google, Baidu, Wikipedia (English and Chinese versions), Unihan, Wiktionary, and Dictionary.com (this feature alone is well worth the money!)

- Words you search for are automatically added to the history so you can easily review them later.

- The “Trainer” feature quizes you on words you’ve saved as flashcards. You can create flashcards with the search results, from your favorited terms, and from words in your history.

YellowBridge (黃橋 HuángQiáo) is one of the best online Chinese dictionaries available today. When I studying on or near my computer, it is the first place I go if confronted by new Chinese vocabulary or characters. (If you are studying on the go, however, check out my article on the best Chinese dictionary apps for Android and iOS4)

YellowBridge (黃橋 HuángQiáo) is one of the best online Chinese dictionaries available today. When I studying on or near my computer, it is the first place I go if confronted by new Chinese vocabulary or characters. (If you are studying on the go, however, check out my article on the best Chinese dictionary apps for Android and iOS4)

Here’s a rundown of the good and the bad of YellowBridge:

The Good

- It’s free! For being so feature-rich, we are lucky to have access to Yellow-Bridge for a grand total of zero dollars.

- Audio recordings: This wonderfully useful feature used to be available only to paid members, but is now free to everyone. Hurray! Just click the speech bubble below each term to hear it pronounced.

- Presentation of both Simplified & Traditional Chinese Characters: This is a Godsend. While most Chinese learners end up learning “Simplified Characters” (简体字 JiǎnTǐ Zì) since they are what’s used in Mainland China, I highly recommend that you also learn “Traditional Characters” (繁體字 FánTǐ Zì). Not only the traditional forms still used in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and many Chinese communities across the globe, but they give you direct access to ancient Chinese culture. And if you are going to learn both, it is far easier to go “downhill”, that is, starting with the traditional forms and then moving onto their simplified counterparts.

- Multiple search options: You can search from Chinese to English, English to Chinese, and even Pinyin to Chinese.

- Break down of character radicals and components: This is a linguists dream. YellowBridge includes links to the etymological origins of each semantic or phonetic chunk. Be careful though; it is easy to get lost in the details and forget what you originally went there to look up!

- Animated stroke order: This is an amazingly powerful tool that used to available on only the most expensive electronic dictionaries. Now it’s free online. If only I had started learning Chinese characters ten years later…

The Bad

There are few things to complain about with YellowBridge. There are, however, a few things missing that I hope they eventually add to the mix:

- Example sentences: It’s always helpful to see how a given word is used in a sentence, especially when looking up less common words, or terms with multiple meanings.

- Ability to translate entire phrases: As it stands, YellowBridge, like most dictionaries, only translates words and cannot parse complete phrases or sentences as Google Translate does. It would be great if they could someday add this feature, lest otherwise faithful users jump ship and swim toward Googler shores…

- A mobile app: I usually need dictionaries most when I’m out on the go and see something on a sign, in a food menu, or struggle to communicate a particular word with the person across the table at a coffee shop. While you can of course access the dictionary via your mobile device’s web browser, it would make life much easier if they developed a mobile version for iPod Touch/iPhone, Android, etc.

Antonio Graceffo is an applied linguist, and martial arts and adventure author living in Asia (check out our interview with him here). His books, including ”The Monk from Brooklyn”, are available at Amazon.com.

Normally, ALG says you do 800 hours of listening, then you start speaking, and you do writing and reading last. The reality is, however, if you are not at the ALG school in Bangkok, it is nearly impossible to arrange these type of lessons for yourself. And, strict ALG takes two years to learn a category three language, such as Chinese, Thai or Korean. Most people working in a foreign country can’t invest two years in learning, particularly if they are on a one year or two year contract.

Normally, ALG says you do 800 hours of listening, then you start speaking, and you do writing and reading last. The reality is, however, if you are not at the ALG school in Bangkok, it is nearly impossible to arrange these type of lessons for yourself. And, strict ALG takes two years to learn a category three language, such as Chinese, Thai or Korean. Most people working in a foreign country can’t invest two years in learning, particularly if they are on a one year or two year contract.

So, I modify ALG when I am doing my own learning and writing.

Next, the founders of ALG were concentrated on how to teach Thai to foreigners. In taking ALG out of Thailand and applying it to other countries, my personal feeling is that the game changes a bit because, unlike Thai, Korean is not tonal and the pronunciation is simple consonant vowel, consonant vowel. And second, the Thai writing system is extremely complex and you really shouldn’t learn to read until you have a very functional knowledge of the language. But in the case of Korean, Hangul is one of the easiest and most perfect writing systems ever developed.

Most people can learn Hangul in about a week, after that, you can read literally anything in Korean. Normally, I tell people to read last, because when you read you have an internal monologue which will be imperfect if you haven’t done sufficient listening first.

What I suggest, to speed up the process, but to also learn the language well, is to buy a university level Korean textbook, and hire a private tutor. Korean teachers will generally want to spend the first several lessons on the alphabet. Don’t let them. Don’t worry about the alphabet for a few weeks. It is probably better to hire a young university student who you can intimidate into teaching you the way you want to learn, as opposed to hiring an experienced teacher who only knows one way and will argue and fight with you.

Have your tutor read the dialogues in your book again and again. At home, listen to the audio CDs for the book. Do not start by having the teacher teach you the symbols or the characters of Hangul. Just follow along with your finger while the teacher reads. Do this for two or three weeks. You will begin to make guesses about what the different characters should sound like. You will begin to recognize words. You will slowly gain a rhythm for the language.

After several weeks, then you could spend a single lesson on the alphabet, to ensure that you know what each letter sounds like and how to recognize them. After that, you can read on your own.

At night, follow the written words on the page while you listen to the CDs. You can start writing at this point. It will help reinforce what you are hearing and learning. But remember, listening is still the key to learning a language and to avoid fossilizing mistakes. Never write an assignment and allow the teacher to take it home and mark it. You go over every assignment, verbally with your teacher, a number of times before you go home and write it. The next day, you should go over your homework verbally, with your teacher. Again, the teacher reads and corrects. You just listen and write. Think about your homework as a talking point, something to help you focus and contextualize your listening.

Don’t speak yet.

What I did with the Korean language was to buy as many level-one textbooks as I could find. There are about three or maybe four series of Korean textbooks sold in Korea. So, I bought all of them. I chose one that I only did with my teacher. The others I did on my own. You can get level one textbooks for free, just ask other foreigners who gave up on learning Korean. They will often pass the books on to you. Just write in them and fill them with ink, writing and rewriting each exercise.

My teacher and I went on like this for about a month or six weeks. Everyday, she read for me. In the evenings I listened to the listening for that book and the listening for the other books which I read on my own.

Eventually, when I started speaking, I only read out my answers from my main textbook while my teacher and I marked my homework.

With Korean language, the listening/speaking is not difficult in the sense of getting the pronunciation right. Actually, Korean, like Mandarin, has only a couple of sounds that we don’t have in English. BUT the listening is difficult because of the complex Korean grammar and registers of speech. So, when you first start “speaking” it should really be just reading grammatically correct and appropriate answers from your book. I did this for hours with my teacher. Occasionally she would ask me something that wasn’t in the book, but I would refuse to answer. You don’t want to start “creating” speech until you are ready. Stick with canned speaking practice for several more weeks.

Finally, you can start speaking. Again, it would be best to wait till the end of 800 hours, but this is not a reality for most people living in the country. So, maybe you start speaking at the end of two months of lessons. My vocabulary was already 2,000 words when I began speaking. And even then, I kept my speaking limited to what was in the book and eventually variations of what was in the book. You should move your reading and listening away from the book and into the real world pretty early on. But your speaking needs to stay in the sterile book world or you will create mistakes that you will never, ever be able to shake.

With all of my languages, once my listening gets to an acceptable level, I encourage people in the real world to talk to me in Korean, but I answer in English. The longer you stay at that level and the more total listening you do, the better your Korean will be when you open up your mouth and start speaking.

If you jump right into speaking, as most teachers want you to do, you will most likely never approach fluency. You will make errors of grammar and appropriateness of speech. Depending upon how early you start speaking you may even make mistakes in pronunciation which is truly sad because Korean is so perfect and easy to pronounce.

The keys to language learning are: dedication, hard work, listening, and discipline to avoid giving in to the temptation to speak too early.

Like Antonio’s writing?

Check out some of his fantastic books on travel, martial arts, language learning and endangered cultures.

]]>

I first came across Walk, Talk & Learn French not in iTunes where I usually get my podcast fix, but via Tivo! I had no idea that you can stream or download podcasts directly to set-top boxes. How cool. But enough tech geekery. Let’s get to the review.

I first came across Walk, Talk & Learn French not in iTunes where I usually get my podcast fix, but via Tivo! I had no idea that you can stream or download podcasts directly to set-top boxes. How cool. But enough tech geekery. Let’s get to the review.

The Good

As with all programs in the Radio Lingua Network, production quality is high.

Each lesson begins on the streets of France, centered around the language used on a movie poster, billboard, or other authentic language material found on the street, in the subway, etc. This authenticity makes the material far more interesting than a bland textbook or audio-only podcast, increasing the ease of retention and ensuring that the language used is actually what native speakers say or write, not what some grammar maven thinks you should say (a common problem in most foreign language learning materials and classrooms…)

The host of Walk, Talk & Learn French, Pierre-Benoît Hériaud, is personable and excited about the language, an enthusiasm that easily spreads to you the viewer.

But this is where, in my opinion, “the good” elements end…

The Bad

Just when you think an episode is going to continue with other interesting sites and sounds on the streets of France, things devolve into a dry grammar lesson with Mark Pentleton, the director of Radio Lingua and host of Coffee Break Spanish, Coffee Break French, etc.

To be fair, most learners expect (and some demand) a formal explanation of the underlying grammar, and Radio Lingua is probably wise from a business perspective to provide what customers demand. The problem is that such an approach does not efficiently lead to oral fluency in a language; the obvious goal of most language learners.

While an occasional glance at conjugation tables doesn’t hurt, overt study of the grammar is not a requirement and is in fact what leads most would-be language learners to failure. Despite hours and hours with one’s nose in a book (or one’s butt sitting in a classroom), the vast majority of people find it impossible to:

a) remember the patterns

b) apply the patterns

c) pick out the patterns in what is said back to them.

As stated countless times elsewhere on Foreign Language Mastery and other language learning sites worth their mustard, the key is getting lots of interesting, comprehensible input (which I think Walk, Talk & Learn French could accomplish if they just let Hériaud run wild and didn’t interrupt the fun with a formal grammar lesson).

Given enough input that is not too hard or too easy, enough interest in the subject matter, and enough time on task, your brain (at a subconscious level) will eventually figure out the patterns and learn when to apply -ai, -as,-ons, -ez, -ont, etc.

]]> In addition to endless English listening input, Hulu.com is now a source of reading input, too. How could a TV site be used for reading input? The answer is closed captioning. Though intended for the hearing impaired, English captions are a wonderful tool for non-native speakers of English.

In addition to endless English listening input, Hulu.com is now a source of reading input, too. How could a TV site be used for reading input? The answer is closed captioning. Though intended for the hearing impaired, English captions are a wonderful tool for non-native speakers of English.

Thanks to Hulu’s new caption search feature, it is easier than ever to use closed captioning for language learning. Here’s how:

- If your reading skills are stronger than your listening abilities, try reading through the closed captions before you watch an episode.

- If you are watching a video and unsure of what was said, you can repeat a given section again and again until it is clear.

- If you want to go back and review the vocabulary from a particular episode again later, you can simply search for terms used during the show, and then automatically jump to the clip using that language.

The only downside is that Hulu is not available outside of the United States, so English learners living in other countries won’t be able to use this amazing tool.

Maybe TV isn’t so bad after all?…

To learn more, check out the following video and visit Hulu’s Caption Search page.

]]>Antonio Graceffo is a martial arts and adventure author living in Asia (check out our interview with him here).

His books, including The Monk from Brooklyn, are available at Amazon.com

Vietnamese is one of only two major Mon-Khmer languages, the other being Khmer, the national language of Cambodia. Like Cambodia, Vietnam is a former French colony. And so, the Vietnamese language has acquired some loan words from French. I am not yet an expert on the Vietnamese language, but so far it appears that the bulk of the loan words are for concepts which the French introduced to Vietnam, such as: Nô-en (Noel), phó mát (cheese), and ca vát (neck tie).

Vietnamese is one of only two major Mon-Khmer languages, the other being Khmer, the national language of Cambodia. Like Cambodia, Vietnam is a former French colony. And so, the Vietnamese language has acquired some loan words from French. I am not yet an expert on the Vietnamese language, but so far it appears that the bulk of the loan words are for concepts which the French introduced to Vietnam, such as: Nô-en (Noel), phó mát (cheese), and ca vát (neck tie).

Because of Vietnam’s close proximity to China, and a long and turbulent shared history, there is a significant Chinese influence on the Vietnamese language. Sixty percent or more of the vocabulary is Chinese. Chinese words are often easy to spot because they are one syllable words. Khmer words are normally multi-syllabic. Some Chinese words will consist of more than one Chinese character, put together, but these are compound words, and even in Vietnamese, these words would normally be written as two one-syllable words, with space between them.

Even the country name for Viet Nam is taken from Chinese, with Nam, Vietnamese for south, coming from the Chinese word for south, 南 (nán).

It is very telling to see which words in Vietnamese were borrowed from Chinese. For example, words related to education and school subjects are Chinese. History – lịch sử in Vietnamese, 歷史 (lì shǐ) in Chinese. So, the word for history is clearly a loan word, from Chinese, and the pronunciation is fairly similar. Intelligent, thông minh in Vietnamese, 聰明 (cōng míng) in Chinese. Again, it is nearly the same.

Some compound words and loan words are extremely interesting, because they combine Khmer and Chinese or Khmer and French. For example, the Vietnamese word for glove can be bao tay or găng tay. The word “tay” is the Khmer word for hand. In the first example, bao is the Chinese word for wrap, package, or cover. So, the literal meaning is a covering for your hand. In the second example, “tay” is still hand but găng is most likely the Vietnamese pronunciation for the French word for glove (gant).

Dictionary in Vietnamese is từ điển, in Chinese it is 詞典 (cí diǎn). The second syllable of both of these words is nearly identical. The first syllable is pronounced differently, but clearly comes from the same Chinese root.

Study in Vietnamese is học, and university is đại học. If the Vietnamese use Chinese characters to write the title of a university they use the same traditional characters as Taiwan or Hong Kong. Study would be written 學 And university would be written 大 學. But the interesting thing is the pronunciation. In Chinese, study is pronounced xué and university is dà xué (literally meaning “big study”). But the Vietnamese đại học, although using the same Chinese characters, would have a pronunciation much closer to Korean (대학 dae hak) than to modern Mandarin. This is most likely because the loan words in Vietnamese and Korean came centuries past, before the Mandarin dialect became standard Chinese. Another similar example is “dormitory”: ky tuc xa in Vietnamese, and 기숙사 (gi suk sa) in Korean. The Korean and Vietnamese pronunciations are quite similar. They would both use the same set of three Chinese characters, but the pronunciation would be completely different from modern spoken Mandarin, 宿舍 (sù shè).

Another example of a connection between Korean (or older Chinese) with Vietnamese would be the word for happy, hạnh phúc, as in, “I’ll be happy if someone gives me a crossbow.” The modern Chinese word for “happy” is 高興 (gāo xìng). So, it isn’t even close, but the modern Korean word 행 복 (hang bok), is almost the same.

Sometimes all three languages align. The Vietnamese word for “romantic” (lãng mạng) is almost identical to both the Chinese 浪漫 (làng màn) and the Korean 낭 만 (lang man).

Telephone, điện thoại in Vietnamese, is 電話 (diàn huà) in Chinese. In both languages the word điện means electricity. So, this character 電 (điện) appears in nearly all appliance names, in both languages. The Vietnamese word for machine is máy móc and everything from an airplane, máy bay, to a motorcycle, xe máy, includes this machine word. In Chinese, however a computer is seen as an electric appliance, 電腦 (diàn nǎo, literally “electric brain”) whereas in Vietnamese, the computer is a machine, máy tính.

While the word for motorcycle and airplane use the Vietnamese word for machine, the word for car is clearly a loan word from French, ô tô.

The Chinese word for machine is 機器 (jī qì). So, it is not similar in pronunciation to the Vietnamese word, máy. But the function is the same. Airplane, máy bay in Vietnamese is 飛機 (fēi jī) in Chinese. Both Chinese and Vietnamese create the word airplane as a compound word, composed of two syllables, written separately, one of which means “machine”. Camera is máy ảnh in Vietnamese, 照相機 (zhào xiàng jī) in Chinese. Again, the overall word for camera is different, but both Vietnamese and Chinese have created a compound word for camera which contains the respective word for machine plus the respective word for picture or photo.

Many language learners put great emphasis on words. They want to learn vocabulary, thinking that learning a language and memorizing lists of definitions is somehow the same thing. Obviously, they are nearly completely separate from each other. If you were a native speaker of French, Chinese, and Khmer learning Vietnamese, you would still need to acquire, grammar, usage, and pronunciation, as well as cultural-linguistic elements, such as forms of address and appropriateness of speech. So, even a triple native speaker would be a long way off.

Studying the mechanical parts, the elements, the words of a language is, however, an interesting academic pursuit. In the case of the Vietnamese language, it is fascinating to see how so many components of the language can be traced to some other language, and yet Vietnamese is completely unique.

____

Like Antonio’s writing?

Check out some of his fantastic books on travel, martial arts, language learning and endangered cultures.

]]>

Antonio Graceffo is a martial arts and adventure author living in Asia (check out our interview with him here).

His books, including The Monk from Brooklyn, are available at Amazon.com

“The rabbit and the lion walked through the jungle. All of the animals ran away. Afterward, the rabbit said to the lion, ‘I told you they were all afraid of me.’”

“The rabbit and the lion walked through the jungle. All of the animals ran away. Afterward, the rabbit said to the lion, ‘I told you they were all afraid of me.’”

This was the story I struggled through last week. Yes, I was sort of proud that it was written in Chinese, but it is quite humbling that most of my reading material is purchased in the books section of Toys R Us. Some of them came with free candy. Others were pop-up books. I particularly like those. All of them are decorated with little cartoon drawing of smiling monkeys and happy flowers.

If your ego gets away from you, as mine often does, just ask the nearest seven year old to help you with your reading practice. This will bring you back to Earth in a hurry.

Learning to read and write Chinese turns you into a study hermit. Chinese children spend five hours a day, from about age five to age fifteen or sixteen, writing endless lists of Chinese characters. In other words, it takes them ten solid years of studying five hours a day, seven days a week, to learn their native tongue.

One reason it takes them so long is because every single piece of vocabulary has to be taught. When you learned to read and write in school, your teachers taught you some very basic vocabulary. Probably through about sixth grade you had spelling tests and vocabulary exercises, but you were only taught a very small percentage of your vocabulary, the rest you acquired passively from listening and from reading and studying your other subjects. But for Chinese, every single piece of vocabulary has to be taught. Even native speakers can’t do much with a word they can say, but don’t know how to read or write.

As an adult foreign-learner you are at a huge disadvantage compared to the native speaker children. For one thing, they already know the meaning of every word.

When you first sign up for Chinese classes, in Taiwan or China, you are given a choice of speaking and listening only, or the complete set of reading, writing, speaking and listening. When I first began learning Chinese at Taipei Language Institute, for the purposes of survival, I chose speaking and listening only. At that time I was the only foreigner on two Chinese Kung Fu teams, training with each team once per day. This gave me several hours of exposure to the language each day outside of the 2-4 hours per day I spent in the classroom. As a dedicated learner, with the opportunity to hear and practice the language, I reached a point where I was getting through a chapter of our book every two and a half days.

One of my American friends, call him Jim, chose the complete set of read, writing, speaking, and listening. In the six months that it took me to complete all of the books from beginner to upper intermediate, he hadn’t completed book one. He could read and write every single word that he knew, but he knew only about 1,000 words when he left Taiwan.

We had another classmate, call her Su Ling, who was a Taiwanese American. At home, her parents only spoke Taiwanese. So, she had returned to Taiwan to study Mandarin for the first time in her life. She could neither read, write, speak, nor understand any Mandarin.

The three of us went to a restaurant, and the waitress automatically handed a menu to Su Ling, and began speaking to her in Mandarin. I interrupted, explaining to the waitress that, in spite of her looks, Su Ling didn’t speak Mandarin. The waitress smiled politely, and resumed her incomprehensible babble with Su Ling.

“Tell her again.” Said Su Ling, “I don’t think she believes you.”

When I finally was able to convince the waitress that I was the one she needed to talk to, she handed me the menu, which I immediately handed to Jim, the only one of us who could read. Jim read the menu aloud, which I understood, but we had to translate into English for Su Ling. When we decided on our order, I told the waitress what we all wanted.

Basically, the point of the story is, if you can’t read Chinese, it takes three people to order off a menu. And, since I often find myself dining alone, I needed to learn to read.

I returned to Taiwan in June 2008, and began taking private lessons in reading and writing in late July. Once I got through my first hundred characters, I realized that learning reading and writing would be a very, very different experience than learning speaking.

When I was learning to speak, I spent as many hours in front of my teachers as possible. The only way I could get any input, any new learning, was sitting with my teachers. But in reading and writing, you have to do it all yourself. The best student will be the one who puts in the most hours of homework. Before, I had the teachers teach me the new material, and I saw them twenty or more hours per week. Now, with reading and writing, I have to teach myself the new material. I work through the chapters completely on my own, and then meet with my teachers just to correct, or go over what I have already done on my own. My ratio now is only six to eight hours per week of lessons and twenty or more hours per week of self-study.

When we were at Taipei Language Institute, I remembered Jim telling me, “With the Chinese, for every single word you learn, you have to learn three things: the way it looks, the way it sounds, and its meaning.”

It’s true. With Chinese, unlike any European language, it is possible to know thousands of words, and not be able to read them or write them. This is where I was when I started studying. The other possibility is that you see a word. You know how to pronounce it, but you forgot what it means. Or, that you remember the meaning, but forgot how to say the word.

One example is that the Chinese have about three ways to express the concept of “a week.” Each of these is composed of two characters. Very often I am reading, and I know the sentence says, “I study Chinese three times per week.” I use the word “xin qi” to express one week, but my teacher corrects me. “These are the characters for ‘li bai’ which also means week.” Two different sets of characters can have the same meaning, but different pronunciations. In English we have a lot of synonyms, which are written and spelled completely differently, but have similar meanings. But, because of our phonetic writing system, it would be impossible to look at the word “demise,” and say “kick-off.”

For myself, the last two don’t happen as often because my vocabulary, going into my basic reading class, was already well over 2,000 words. So, while I could maintain a fairly normal conversation, my reading book has sentences like, “My name is.” and “How many glass of tea did Mr. Wang take?” When any of my Taiwanese friends open my textbooks they always look at me in surprise. “This is so easy. You are way beyond this.” They learned to read so long ago that they forgot that someone who speaks Chinese well may not know how to read at all.

Interesting, my second-grade students don’t think there is anything strange about what I am doing. They watch me do my homework and often say proudly, “Teacher, I can read all of that.” Half way through the page, though, they inevitably stop and ask me, “What is this word?” Yesterday, one of the kids asked me about five different Chinese characters in my homework. I was so proud of myself. If I study really hard, I might qualify for elementary school.

In learning to read, I thought a lot about what Jim said. And, although I understand the concept of why, at universities in the west, students are taught all four skills from day one, this must be a very daunting, very discouraging way to learn. Progress would be so slow. In my case, having learned so many words first, even with reading and writing I am getting through a chapter every three days. This is only possible because I already have the speaking and listening. Maybe this method of study would be better for university students in other countries. Maybe it is only possible if you are studying in a country where the language is widely spoken.

So much about L2 (second language) acquisition has been written based on how children acquire their L1 (first language). There are some fundamental differences, however, namely that an adult has more logic and experience to draw from. An adult also understands the mechanics and use of language. When I teach second graders that they have to use good grammar, they may not even be aware that Chinese has grammar. And certainly, their Chinese grammar wouldn’t be perfect yet.

One point that makes my current study of Chinese reading and writing more similar to the way Taiwanese children learn is that, like a Taiwanese child, my vocabulary is already large and I am already able to speak and communicate. Now, I have to learn the reading and writing. Even in the more advanced reading books, if I get stuck on a word, it is normally because I don’t know how to pronounce or recognize a particular character. But, if my teacher reads the character, I understand. This is exactly the case for Taiwanese children.

There are huge differences in vocabulary and usage, however, but more on this later.

One of my Tainan friends, call him Chuck, has lived in Taiwan for twenty years. He learned all four skills from day one. He had some very interesting points to make about language. First, he said, “I studied hard for the first five years. Then I took the exam and I scored 3,000.” Meaning his test results showed that he knew 3,000 or more characters. Three thousand is the magic number. At that level you should be able to read anything, even college textbooks, but you will still need a dictionary for specialized vocabulary that you may encounter. “I stopped studying at that point,” continued Chuck. “And my Chinese stopped improving. I recently retook the test and still scored 3,000, so I haven’t lost anything. But fifteen more years of living here didn’t cause me to improve.”

Chuck was touching on a subject I have written about extensively, namely, being in the country doesn’t mean you are immersed or that you are learning. Chuck has lots of Taiwanese friends and speaks Chinese all day, but in the course of a normal day or normal conversation, he doesn’t go beyond his three thousand words. The only way to move forward is to study.

Chuck also said, “There is nothing anyone can do for you when you learn to read or write. Even your teachers can’t really help you. If you get stuck or you make a mistake, they can correct you. But you have to learn it on your own.”

And this means countless, lonely hours of reading and writing. Reading and writing Chinese, you become a study hermit.

Chuck told me about a foreigner who was teaching in Taiwan in the 1980s when the country was a bit less developed and regulations were in some ways looser. This foreign adult wanted to learn Chinese, so he went to an elementary school principle and obtained permission to attend classes, along with the children.

“For four years he sat in the back of the classroom learning the stuff children learn,” said Chuck. “But to me, it seemed a little pointless. He didn’t need to know the name of every utensil in the house.”

Now we are back to the differences in vocabulary and approach of an adult learner, verses a child. I haven’t tried it, but I would bet money that if I took my basic reading dialogue entitled “At the Money Changers” and showed it to my second graders, they wouldn’t be able to read any of it. And if I read it aloud, the probably wouldn’t know words like currency exchange, travelers checks, or the technical names for currencies such as American Dollars or New Taiwan Dollars. They might not even be able to read the rates, which are posted in decimal form. At the same time, I don’t know how to say baby bottle or game consul. And I always forget what to call your father’s younger brother.

And perhaps most embarrassing, the second graders didn’t stutter when they were reading the story about the lion and the rabbit. It took me two days to read that.

This hits on my other writing focus. There is a myth that children learn language faster than adults. It’s just not true. For my work as an adventure writer, I need a lot of specialized vocabulary in the fields of international relations, politics, and geography. There is no way second graders would understand any of the concepts, so how would they learn and use that vocabulary. Often, we are talking about a second grader’s inability to learn these words and concepts in a foreign language. But now, I am comparing me, and adult learner, learning Chinese, to native speaker second graders. While they have many advantages in general reading and writing, by virtue of being native speakers, it will be years before they could read and explain the texts I will be using at university, a few months from now. And of course, if we compare an adult foreign leaner to a child foreign learner, the difference becomes even more extreme.

Learning to read Chinese means memorizing one or more characters for every single piece of vocabulary in your head. The characters are based on over a hundred base characters. So, after a while, you can see a new character and guess that it has something to do with talking or driving or is esoterically related to the heart or an open door, but for the most part, it is pure memorization.

The Chinese language is like an epic movie, starring a cast of thousands of characters.

Like Antonio’s writing?

Check out some of his fantastic books on travel, martial arts, language learning and endangered cultures.

]]>

This interview was originally done for my site, book and podcast series Living, Learning & Teaching in Taipei. This “information triumvirate” shares useful tips and tricks on how to learn Mandarin and martial arts, teach English and have a ridiculously good time living in Taiwan’s capital.

This interview was originally done for my site, book and podcast series Living, Learning & Teaching in Taipei. This “information triumvirate” shares useful tips and tricks on how to learn Mandarin and martial arts, teach English and have a ridiculously good time living in Taiwan’s capital.

For more about Steve, see my article Steve Kaufmann: Founder of LingQ, Creator of “The Linguist on Langauge” and Author of “The Way of the Linguist”.

In the interview, Steve delves more into his Pick the Brain article, “7 Common Misconceptions About Language Learning”. To help you follow along in the conversation, these 7 misconceptions are:

- 1. Language learning is difficult.

- You have to have a gift for learning languages.

- You have to live where the language is spoken.

- Only children can learn to speak another language well.

- To learn a language you need formal classroom instruction.

- You need to speak in order to learn (and I have nobody to speak to).

- I would love to learn but I don’t have the time.

Listen

To listen to the interview, click the red button below:

___

Read

John: So what I’d like to pick your brain about is the article you posted on Pick the Brain: 7 Common Misconceptions about Language Learning. I think that has a lot of good stuff in their to help my listeners get started with Mandarin and avoid the most common pitfalls that most language learners encounter.

Steve: Alright then. Well, the first one that I hear so often is that language learning is difficult. We hear that particularly here in North America. I think we hear it in countries like Japan. And the problem normally is that the person isn’t sufficiently motivated. Language learning is not difficult; we all learned our first language. And I think it’s also made difficult because of the way it’s taught in schools, where people are forced to try and perform in the language at a point where they have no chance of performing in the language. If we learn in a natural way, mostly listening and reading, and if we enjoy doing it, it’s not difficult.

The second misconception is that you have to have a gift for learning languages. I speak 10 languages, so people just say, “Oh, well you just have a gift.” I don’t believe that and I’ll tell you why. If you go to countries like Sweden, Holland or Singapore, everybody speaks more than one language. It’s not a big deal there. I don’t believe that Singaporeans or Swedes have some kind of a gene that makes them more gifted for languages.

I’ve also noticed that here in North America where we have foreign athletes, such as Russian hockey players, after a year or two, the Russian hockey player speaks English much more fluently than the average teaching assistant that we have from Russia at our universities who no one can understand! And the point is that the hockey player is in with his buddies. He’s in an environment where he just has to communicate. He’s happy. He’s just doing it. Where as the college professor is more, you know, academic and probably a little more inhibited. And I don’t believe that hockey players have a gene that makes them better language learners than college professors. So I don’t think that you need to have a gift to learn languages.

What is true is that having the right attitude can help, and just being willing to let go, and listen and communicate.

And the more languages you learn, the better you get at it. Me learning my tenth language, Russian, I’m a better language learner at 63 than I was at 16, 17 when I wanted to conquer French.

John:Alright. Number 3?

Steve: Yeah, well people say that if I only lived where the language is spoken, then I’d learn it, or I could learn it. Of course it’s an advantage to live surrounded by the language, but it’s not a condition. I learned Mandarin in Hong Kong, which is not a Mandarin speaking area, and in fact, when I lived there in 1968, 69, you didn’t hear Mandarin anywhere, just about. So I learned it despite the fact that I wasn’t surrounded by the language. And on the other side of the picture, I lived in Japan for 9 years, and most North Americans, Europeans living in Japan did not learn Japanese. And we’re all familiar with immigrants who live here in North America for 20 or 30 years and never learn to speak English. So it can help to live where the language is spoken, not living where the language is spoken doesn’t prevent you from learning the language, and there’s no guarantee that if you live where the language is spoken, that you’ll to speak it.

John: Yeah, I can attest to that. There are hundreds and hundreds of foreigners I encounter here who have been here many years and can barely get by in the language. And I would say that it just reiterates what you said in points 1 and 2: they think it’s difficult, so they don’t even try, or they think that they’re not good at languages, so they don’t try.

Steve: Exactly. And the thing is, today with the iPod MP3 player, you can literally carry your immersion around with you, and you can listen all the time.

John: Oh yeah, I’m plugged in 24/7. They’re fused into my ears now.

Alright, number 4.

Steve: Well, this was about that you have to be a child, that there is a critical period, and all of this. I think that there is a critical period for your native language, when native language forms, but there’s all kinds of research that shows that our brains retain their plasticity. Adults who suddenly become blind can learn Braille, which is a language.

Children have some advantage in that they’re less inhibited. But children don’t have as wide a vocabulary as adults. I mean here I am, I’ve learned Russian in 3 years; I can read Tolstoy essentially with no trouble. I don’t think a 3 year old child could put in 3 years into Russian and learn to read Tolstoy.

So children have a number of advantages, mostly that they are not inhibited; they’re not afraid to be childish! The educated person is reluctant to speak another language because they think they sound like a fool because they can’t express themselves. And children don’t worry about that. So I think that’s not an issue; you can learn a language at any age.

John: Alright, well, the next one is one of the most important and one of the hardest, I think, for those of us who are teachers ourselves, to accept. But I do completely agree; hopefully my listeners will as well.

Steve: Well, the thing is that the classroom has a lot of advantages. One of things about the classroom is that it’s a social place: people get together with the teacher, with the fellow students. It’s a place where the teacher can inspire the students, can push them, give them assignments. There’s lots of things that can be done in a classroom, but you can’t learn in a classroom in my opinion.

A classroom is a place where you mobilize people and encourage them. Or they encourage each other. But the learning, the language learning, has to take place outside of the classroom. But the role of the teacher is to make the student inventive, and make the student so fired up, or so afraid, one of the two, that they’ll go and do something on their own.

So if you want to learn and if you are motivated enough on your own, you don’t need the classroom. Unfortunately, that’s a small percentage of learners. Most people need the classroom in order to be motivated, disciplined and stay on the task. The challenge for the teacher is how to use that classroom effectively so that for every hour in the classroom the student puts in 3 outside the classroom.

John: OK, perhaps we can expand on this a little bit. What advice do you have for teachers who perhaps agree with these seven misconceptions and are trying to structure their classrooms in a way that doesn’t demand immediate output, isn’t relying on testing and memorizing grammar rules and all these things?

Steve: You know, it’s hard for me to say because I have not taught in a classroom. However, when I see the results of classroom instruction, and I often quote this extreme example in New Brunswick here in Canada. New Brunswick is a bilingual province. 1/3 of the population speaks French. In the English language school system, they have French 30 minutes a day for 12 years. And they surveyed the graduates after 12 years, and they found that the number who could achieve what they call an intermediate level of oral proficiency in the French, was 0.68%! After 12 years of 30 minutes a day, zero point six eight percent achieved an intermediate level of proficiency! They might just as well not have bothered. Because I am sure that number would have done it anyway.

There’s a Center for Applied Linguistics in the United States that did a survey on the impact of instructional hours on immigrants learning English. In some cases it went down! Now it didn’t go down because of the classroom; it went down because the classroom is irrelevant! Over a period of time, people will improve in their English. And if they had tracked other factors like: Where does the person work? Does he watch videos at home in his native language or in English? Who are his friends? What is his attitude? All of these things would of had a much bigger impact than classroom instructional hours.

So I think the teacher has to begin by realizing how relatively ineffective classroom instructional hours are from an instructional point of view. OK, so what’s the classroom for? The number one goal of the teacher is to motivate the learner. And the number of people who will really improve is limited. You want to increase that number. The number that will really improve are the one’s who are motivated.

How do you get them motivated? I think if I ran a classroom, I would do what we do at LingQ. I would have either individual students or groups of students choose what they want to learn from; choose content to listen to and read. And spend most of their time with content that’s of interest to them. Maybe you do it in groups. Here, groups of five. Here are ten subjects. Divide yourselves up and go to the subjects you like. Listen to that, read about it.

And then work on vocabulary. It’s words over grammar. You need words. The grammar can come later in my opinion. Once you’ve got enough vocabulary that you can actually say something. And say it wrong a few of times. Or don’t say it! Just listen and read. If you have enough words, you can understand what you’re listening to and reading. And listen, listen, listen. Eventually you’ll want to speak.

So I think I would have more freedom in the classroom, and then groups can talk about themselves, about the subject that they’re studying. If they’re saving words and phrases as we do at LingQ, they can exchange lists of words amongst each other. They can write using these words. But I would break it up in that way. If they’re interested in sports, if they’re interested in gossip, move stars, whatever, just let them. Get at the language. There shouldn’t be this requirement to cover certain items on the curriculum.

John: Alright, so getting back to the seven points here. Number 6: “You need to speak in order to learn.”

Steve: Yeah, I mean at some point you have to speak. I mean that’s the goal; everyone wants to speak. But you can go a long time without speaking. And in the early stages I think it is more productive to do a lot of listening. And especially, initially, repetitive listening. And a lot of listening and reading to build up your vocabulary. So that when you go to speak to someone you actually have some words and you don’t just say, “My name is so and so. It’s a sunny day today” over and over and over again.

There will come a point where you have so many words that you’re ready; now you want to speak. And at that point, then you need to speak a lot. Because you’ve accumulated this vocabulary, you’ve got this tremendous potential ability to speak the language. You’re going to speak with lots of mistakes, with lots of hesitation, you’re gonna have trouble finding your words. Now you need to get out and speak. But that point is not right at the beginning. That point is at some point later on that will vary with the learner and with the language. It could be 6 months later; it could be 12 months later. Whenever you’re comfortable. And there shouldn’t be, in my opinion, this pressure to speak. And nor do you need to speak.

And a lot of learners are lazy. They say, “Oh, I just want to have a conversation.” Well, even in that conversation, if you’re not very good at the language, the most useful part of it is when you’re listening to the native speaker. Because you don’t have much to say if you don’t have enough vocabulary. People sort of say, “Well, I’m embarrassed to go out with people who all speak Chinese. I don’t understand.” You don’t have to speak, just sit there with them. Pick up a little bit here and a little bit there; it’s good for you.

John: I think as long as you can put aside that desire to know right now everything going on around you.

Steve: That’s the key thing. People want to know right now. You can’t know right now. I always say that a language leaner has to accept uncertainty.

The next one was, “I would love to learn, but I don’t have the time.” And we hear that all the time. Make the time if you’re interested. You make time for other things that you like to do. But that’s really where the iPod MP3 players come in. Because when I was learning Mandarin, I had these great big open-real tape recorders. And today I carry a little thing with me that has hours and hours and hours of stuff on it, that I replenish everyday. So there’s no excuse. The main activity is listening, simply because it is so portable. You can have it with you everywhere. And I listen an hour a day. 15 minutes here, half an hour there, I get in my hour. So you have the time if you want to and if you go about it properly.

John: Alright, well, I’d like to change gears a little bit now and get some input on learning Mandarin specifically.

Steve: Alright. Well, the first thing is to not allow yourself to be intimidated by the language. Mandarin is in many ways easy. I think the basic pronunciation of the sounds is easy. The tones is another issue. But the basic making of the sounds is not difficult. The grammar is extremely easy. The way words are created, the way the vocabulary is created, in that different characters are put together in different combinations to mean different things, is very rational. It’s very efficient. So the vocabulary accumulation is very easy. So there are a lot of things that make Mandarin easy.

I think if people have convinced themselves that Mandarin is difficult, that’s a major obstacle. I remember when I went to learn Cantonese and I had somehow had it in my mind that there were 9 tones, that kinda kept me intimidated. Until someone told me, “Forget 9. 6 is good enough, and if you get them wrong, it doesn’t really matter.” So I forgot about the problem, and I just went in there and I learned it. So, the first thing is not to be intimidated.

The second thing is, I think when you first start out, of course, you’re gonna use PīnYīn (拼音), because it’s impossible. You’re gonna have to have something you can read that represents what you’re listening to. But as quickly as possible, you could get into the characters. And you have to find a system to learn these characters. There is the Heisig system; I didn’t use that but many people swear by it.

I had my own system: I started out with 10 characters a day and eventually worked up to 30 a day. And I would take one, and I’d get one of these exercise books that Chinese school children use with the squares, and I would write the character out by hand, you know, 10, 20 times, and then put it over on the next column. And then pick up the next character, and do the same, and put it over one column. So before I had done 2 or 3 characters, I had run into the first one again. So it was kind of like a spaced repetition system. And so I would do that, but there’s all kinds of spaced repetition systems, flashcard systems. Find one, and work on characters.

And work on characters that come from texts you are learning. Don’t learn them in isolation. You’ll never have a chance. And also don’t get discouraged that you forget them. It’s like learning vocabulary. I assumed that if I learned 30 a day, I would forget about 60 percent of them. And then I would relearn them and relearn them and relearn them. And do them everyday. You have to do characters everyday. And I learned 4,000 characters in 8 months, in combination with my reading, but I did them everyday. And I read everyday. So you gotta combine them with reading. You can’t just do it as an isolated exercise. So that’s with regard to characters.

With regard to tones, of course you’re going to try and remember what tone an individual character is, but it’s very hard to do that. It’s like trying to remember whether something is masculine or feminine or neuter German. So at some point you have to let go. And you have to try and imitate the intonation. Listen to it, repeat it, imitate it. And just feel confident that eventually you’ll get better, and that if you’re hitting 20% correct tones, it’ll eventually become 30, and then 40, and 50, and don’t be discouraged. And just keep at it, listening and imitating, listening and imitating, and it’ll gradually get better.